Heâs known by many as the father of the modern soap opera. Others see him as the man whoâll deliver Liverpoolâs year in the sun. But for some heâll always be the QS who tackled Orton village hall âŠ

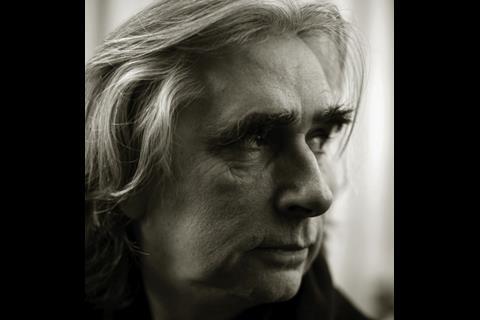

âHey! Careful where youâre leaning there mate!â Phil Redmond looks round at the grinning builder who has called out the warning. âWe wouldnât want you to get paint all over your nice coat.â Elsewhere someone of Redmondâs status would be lost for words, but the silver-maned deputy chair of Liverpoolâs capital of culture committee turns to the man and, in equal good humour, replies: âI thought I could smell paint â I thought the Queen might be coming.â

Her Majesty might not be in town just yet, but a quick walk past the massive ÂŁ1bn Grosvenor project at Paradise Street proves that Redmond is royalty enough. We have only stopped for a few minutes with the photographer and already a small crowd has gathered, taking shots of their own on mobile phones. âWhatâs the story?â one asks. When I start to explain, he says: âI know itâs Phil Redmond. We all know who he is.â More builders are shouting down from the scaffolding above and one even comes over to ask if he can help with any photographs as Redmond is â⊠a great writer, mateâ.

With this much goodwill towards the creator of Brookside and Grange Hill it is little wonder that he firmly believes that next year will be a great one for Liverpool: European Capital of Culture.

How quickly perceptions change. Only in August last year the local press was sharpening its knives for Redmond and the 14-strong capital of culture committee. The much-hyped Matthew Street Festival had just been cancelled at the last minute owing to a âcommunications breakdownâ. Even Redmond admitted that the organisation of the 2008 celebrations had lurched from âcrisis to crisisâ and called for his own committee that was overseeing the work of arts organisation the Culture Company to be scrapped as it was â⊠just a talking shopâ.

Fast forward four months to late December, just weeks before the official launch party at the newly designed (but still incomplete) Liverpool Arena and Redmond claims the picture has definitely improved. He has languidly sprawled himself on a couch on the top floor of the new BBC Radio Merseyside building where he has just finished an upbeat

phone-in show about (what else?) the capital of culture. Redmond brushes aside talk of a ÂŁ20m black hole in the councilâs finances as a result of organising the capital of culture festivities. âThatâs all old news now,â he says, squinting out from under his bushy black eyebrows into the winter sun pouring through the window. âThe agenda has moved on. The culture funding is fine and most of it has been spent and so thatâs it. If we walk away now and donât do anything tomorrow, the art institutions will deliver their programmes. Most of the other things like the community and education programmes will all happen anyway. We at the Culture Company are pretty confident and sound â we have no funding issues.â

There are also now, apparently, no issues about the make-up and role of the much-derided culture committee. Redmond is now deputy chair of a committee that has been pared back from 14 to six â Tom Bloxham, the founder of Urban Splash, and councillor Mike Storey, the cityâs regeneration supremo, also made the cut. Redmond has been given responsibility for driving the creative element of 2008 â that is, pretty much everything. The council must be delighted he has agreed to shoulder the burden as shortly after our meeting Jason Harborow, chief executive of the Culture Company, left his post, citing plots against him that have made his position untenable.

You only have to speak to Redmond for a few minutes to understand that he lives and breathes Liverpool. But can he pull it off?

Liverpool is a city of 285,000 people â Manchester has a

million-plus. But weâre cool and theyâre not

He draws his inspiration from a rather surprising source. âI worked as a QS for five years for a firm called Everest and Blundell.â He got into that after being impressed by a QS who gave a talk at his school, and for the next few years he worked on schools, police stations and other public buildings around the North-west. These included Padgate Teacher Training College in Warrington, Cheshire, and a village hall in Orton, in Cumbria. âI do look back and think that it was actually a good route to go down,â he says. âI do have a lot of respect for the industry. It was five years in construction and 30 years in television and thereâs nothing in television that you couldnât find a parallel for in the construction business. Itâs all about getting particular people to do a particular job at a particular time, within a particular budget and timescale.â (See box below.)

Constructionâs loss has been televisionâs gain and although Redmond says that âdoing all of this forced me to conclude that there must be more to life,â he adds that âas a result of my early training when I first got into television I could see that a lot of the processes could be improved. There is always another way of doing things. If you havenât got the budget that you really wanted, the question you have to ask is what is the original intent for what you wanted to do?â

Redmondâs answer to that question for the capital of culture is âto bring a renewed confidence to the people of the cityâ. He bristles at the suggestion that this will take more than a few gigs by the surviving Beatles, given the cityâs decline and the corresponding rise of Manchester.

âYouâre making a mistake here thinking that we actually care what people think about us,â he says, and for the first time there is an edge to his Scouse drawl.

âThe reason why all of this building work is happening is not because the investors are worried about the image of the city. Itâs going on because they think there is a return to be made.

As for the Manchester question, Redmond insists that it is a false comparison. Whenever Liverpool plays Manchester United, he says, the fans do not see it as symbolic struggle for regional supremacy. âWe are now one city region. I donât see this as an issue at all.â However, perhaps mindful of his audience on the street earlier, he adds: âWe donât want to be Manchester. We donât care. Weâre Scousers and we are what we are.â

He quotes from the Open Culture community website that he and his wife pay for: ââLove us or loathe us, you canât ignore usâ. Weâre a city thatâs always been at the edge of everything and the centre of nothing. It is a town that has been shaped by shifting agendas, constant change, constant decline and constant rise. Weâre comfortable with who and what we are. Liverpool is a city of 285,000 people â Manchester has a million-plus. But weâre cool and theyâre not.â

Redmond onâŠ

Architecture

âI think if Iâd gone into architecture I might still have been there as my creative gene might have found a better outlet.â

Paradise Street

âAnybody in their right mind knows that if somebody announces a ÂŁ1bn scheme and says itâll be ready in April 2008, thatâs

going to slip.â

Legacy

âBy the end of 2008 I hope our built environment changes from a sandstone and cobble 19th-century city to being a glass and steel 21st-century city.â

Once a QSâŠ

âWhen I started Brookside they used to take 90 minutes to run the cables out in the morning and 60 minutes to bring them all back in at night, if we were out on location. By building a permanent set and cabling it, that was reduced to 30 minutes and 15 minutes so we gained an extra two hours a day, almost. Also, the average set construction cost in 1982 was ÂŁ13,000 for every half hour. That meant that Brookside Close was paid for in 13 weeks, and weâd removed the 26 grand overhead every week. The cost of hiring the equipment was ÂŁ1.5m in 1981. That paid back in something like four months so we were able to keep costs right down. All that came from quantity surveying.â

Topics

The Liverpool Issue

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

Currently reading

Currently readingPhil Redmond

- 10

No comments yet