Renzo PianoÔÇÖs Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Centre in Athens puts the Ancient Greek concept of an ÔÇśagoraÔÇÖ or meeting place at its heart. But while it is without doubt a triumph of civic architecture, Ike Ijeh questions whether it lives up to its immense ambition

The ┬ú500m Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Centre is arguably GreeceÔÇÖs defining cultural and architectural project since the 2004 Olympic Games and is probably architect Renzo PianoÔÇÖs biggest architectural project since LondonÔÇÖs Shard. This vast structure has been incorporated into a new 170,000m┬▓ park built in the south-west of the city on an abandoned site that was used as a car park during the 2004 Olympic Games and was a cemetery before that. Only a short distance from the coast, it stands close to the symbolically charged site of AthensÔÇÖ ancient port of Phalerum.

The complex, which is scheduled to fully open to the public later this year, is of national importance as it contains the Greek National Opera House and the National Library of Greece. Both institutions have relocated from older premises elsewhere in the city. The opera house contains two auditoriums, a 1,400 capacity main hall and a smaller 450-seat theatre. The library, which will for the first time offer public access as well as research facilities, has capacity for up to two million books.

Thankfully, considering the continuing precipitous state of Greek public finances, the project has been funded entirely by the privately owned Stavros Niarchos Foundation, an organisation established in the memory of the late Greek shipping tycoon from whom it takes its name and which is run by his family for the purpose of philanthropic cultural endowments.

Situated in an earthquake zone, the entire building marks a technological milestone in relation to seismic design. It is supported on the worldÔÇÖs largest base isolators outside Japan which comprise bearings placed on the foundations that essentially enable the structure to slide in the event of an earthquake.

Architecturally, it is based on three timeless architectural concepts that have a particular resonance to Athens: parks, water and public space. Despite the enduring image of the Acropolis perched on its green summit, the culture of parks and public space is not embedded into the culture of modern Athens, a situation this project seeks to rectify.

Equally, while the coastline to the south-west of the city is studded with stunning Mediterranean beaches, as with many Western cities, the construction of major coastal arterial highways in the 1960s did much to sever vital links between city and sea.

Integrated into a park

The new structure is not merely incorporated into the park, it is literally lodged beneath it. The building emerges from the ground as, in PianoÔÇÖs words ÔÇťa dislodged piece of the earthÔÇÖs crustÔÇŁ with the slope of its roof rising from ground level to a summit of over 35m high at the other end. In this manner it is similar to Henning LarsenÔÇÖs 2014 Moesg├ąrd Museum in Aarhus, Denmark, but this is conceived on a much larger scale. Wisely, despite the topographical similarity, Piano is careful not to directly compare his artificial hill to the Acropolis.

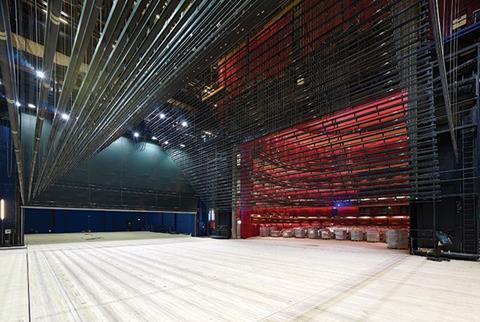

In section, the lower end of the building houses the library and the upper end of the opera house. A deep full-height recess is cut into the centre of the building which houses the twin entrances to the library and opera house at either end. While much of the building is encased in solid concrete, the central recess is framed with glass allowing uninterrupted views into the lobbies within. Also at this point, two soaring flights of external ceremonial staircases extend to the park above.

The park itself is extraordinary. It not only surrounds the SNFCC but extends over the full extent of its roof transforming from a richly planted landscape of olive trees and vegetable gardens at its lower reaches to a hard landscaped series of stepped terraces and staggered platforms as it reaches its summit. A shallow gradient throughout ensures the rooftop park is easily accessible to all members of the public.

The summit is marked by a vast canopy, a remarkable 100m x 100m gleaming white ferrous cement structure supported by a series of slender pilotti. Underneath the canopy a gigantic roof terrace known as the lighthouse extends, providing what Piano describes as a ÔÇťpublic piazza set 30m above the groundÔÇŁ.

By submerging his building within the natural landscape, Piano establishes a new relationship between city and park. As he explains, the exact location of the venue, near the southern Athens suburb of Kallithea which in Greek means ÔÇťbeautiful viewÔÇŁ, helped in this regard: ÔÇťFrom our first observations there emerged the idea that by raising the ground, namely designing an inclined park that would rise seaward from grade, with a slight slope and a progressive course, we could restore the ÔÇśbeautiful viewÔÇÖ of Kallithea. We were convinced the first step would not be design but topography. This is a project that developed by inquiring into heights, dimensions and slopes.ÔÇŁ

The spectacular sea views available from the terrace help address the second concept of water. As does the vast new parkland canal dug beside the SNFCC. At 400m long, 30m wide and 1.5m deep, it provides an appropriately monumental natural counterfoil to the hulking concrete building alongside it.

The final critical concept of public space is handled twofold. First in the sprawling rooftop terrace. And perhaps with even more conceptual resonance, in the large 40m x 40m public square formed in the central ÔÇťrecessÔÇŁ between the opera house and library. Piano refers to this as the ÔÇťagoraÔÇŁ, the traditional meeting or assembly place in Ancient Greece reconfigured here as a public forum for gathering, performance and music.

Coming up short

Clearly, this intensive concentration of cultural amenities has its programmatic origins in other renowned artistic hubs such as New YorkÔÇÖs Lincoln Centre and, more obliquely, LondonÔÇÖs South Bank. However, unfortunately, there are a number of reasons why the SNFCC doesnÔÇÖt quite live up to the comparisons and they can be summarised in three crucial areas, location, language and intimacy.

There is no doubt that the park is a spectacular civic gesture and integrating the building so forcefully into it is a clever symbolic and constructional move. But with the SNFCC submerged so deeply into the centre of the park and thereby requiring a lengthy walk to reach, one wonders if it might not suffer the physical and psychological dislocation from the city around it that is so prevalent at LondonÔÇÖs Barbican.

By comparison, both the South Bank and Lincoln Centre are fully embedded into their respective cityÔÇÖs streetscapes. The extent to which the SNFCC impacts the city will of course depend on the level to which Athenians embrace the new park and, happily, its scale of ambition suggests that over time they will do so with great enthusiasm.

The architectural language adopted is perhaps a more difficult issue. The majority of the building is faced in multiple panels of blank, albeit finely honed, concrete. The only exception is around the ÔÇťagoraÔÇŁ but here concrete is replaced with endless sheets of vertical glazing. The overall effect therefore veers dangerously between the corporate HQ and a giant exhibition centre. There is an anodyne monotony to the treatment of the facades that seriously detracts from the soul and personality one might expect a public building of this importance to have.

The third and possibly most damaging issue is its lack of intimacy. One of the most undoubtedly impressive aspects of the SNFCC is its incredible scale. Of course there is nothing wrong with monumentality, it can present a thrilling physical construct as evident from the temples of Ancient Greece to the skyscrapers of modern China. But even the most monumental buildings need conduits through which they can relate to our smaller, human experience and this Piano has signally failed to achieve.

As in so many contemporary public buildings, the entrances around the ÔÇťagoraÔÇŁ are meek afterthoughts, single storey-scaled doors rendered compositionally irrelevant by the soaring curtain walls looming above them. The differences between this and the soaring entrance arches of the Metropolitan Opera House at the Lincoln Centre could not be starker.

This problem of lack of intimacy could also seriously compromise PianoÔÇÖs aspirations for the ÔÇťagoraÔÇŁ as a bustling public space. When it comes to public realm people have a habit of defying what architects tell them to do and successful public space tends to grow organically rather than by decree. With its separation from the street and its enclosure by cliff faces of glass walls, the spontaneous social activity envisaged for this space might not occur as obediently as expected.

Of course water is an immensely humanising gesture but again, the broad canal with its adjacent esplanade might not work quite as intended. Anyone who has been to Washington DC or the gardens at Versailles knows that a vista works best with a focal point at its end, perspective is our way of humanising scale. But because the SNFCC is placed beside the canal rather than at the end of it, when approaching the ÔÇťagoraÔÇŁ from the park entrance, both building and canal engage in an awkward stand-off where, to all intents and purposes, they appear to operate independently.

The inside story

Internally many of the strengths and weaknesses outside are present too. The entrance lobbies are swooping, vertiginous wood-trimmed voids lined with balconies and awash with natural daylight. The reading rooms display Piano at his best, a series of calm, yet forensically detailed and proportionally controlled spaces lined with bay after bay of Maple wood bookcases. The rehearsal studios too, two of which feature dramatic acoustic ripples along its timber walls, are simple and elegantly defined rooms. Remarkably, due to the presence of a nearby quarry, it also proved cheaper to build fire escape stairs from marble.

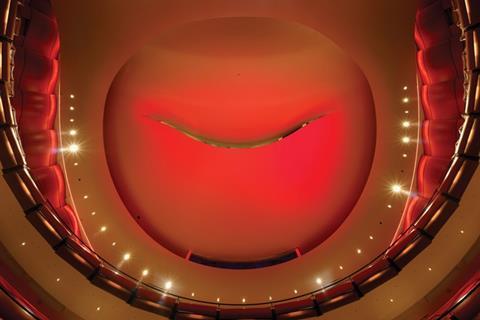

But the interiors are often also marked by a pallid sterility. Mercifully freed from the white box tyranny so evident in modern public buildings, the procession of grey and beige surfaces that replace them form an ill-fitting substitute. This is most evident in the library atrium and, ironically the main opera auditorium, which in clear homage to the historic precedents set by houses like La Scala and Covent Garden, is decadently finished in red. But with its gloss overtones and no evidence of red elsewhere in the building, the gesture appears contrived and synthetic in relation to the rest of the venue, like a tool box that reveals velvet lining when opened.

By far the buildingÔÇÖs most spectacular moment comes at its summit where the park culminates in a stunning roof terrace with breathtaking views of city and sea. It is an act of immense civic generosity and architectural imagination. Fully open to the public and reached by external glass lifts that link it directly to the ÔÇťagoraÔÇŁ, it will undoubtedly surpass the latter to become one of the most sought-after public meeting places in Athens.

But here too awkwardness returns and this time it does so in the form of the canopy. The gigantic canopy is a work of extreme technical wizardry, its ferrous cement panels allowing for a sinuous lightweight, entirely joint-free structure. It also provides a remarkable 10,000m┬▓ of solar panels and offers shade and breeze in sweltering Athens temperatures.

When glimpsed from the park the canopy seems visually feasible and conforms to the classic landscaping aesthetic of a pavilion in the park. But when viewed in relation to the building below, plausibility flees and unnerving similarities to a helipad or car spoiler arise. Canopies are an annoyance at the best of times but here, perched incongruously at the top of a building that until this point emerges from the ground with a certain bland passivity, it conveys all the awkward futility of a eunuch sporting Speedos.

With its luscious park, sublime rooftop terrace and generous cultural offer, the SNFCC undoubtedly represents a remarkable work of civic architecture that will be of enormous benefit to the city of Athens. But one senses that in various key areas such as the canopy, facades and positioning, the architecture struggled to find an appropriate narrative to navigate the immense scale of the task and building at hand.

Photography by Yiorgis Yerolymbos and the SNFCC

Project Team

Client Stavros Niarchos Foundation

Architect Renzo Piano ║├╔ź¤╚╔˙TV Workshop

Main contractor Salini Impregilo-TERNA (joint venture)

Structural engineer (roof) Expedition Engineering

Photovoltaics engineer Arup

Landscape architect Deborah Nevins & Assoc

2 Readers' comments