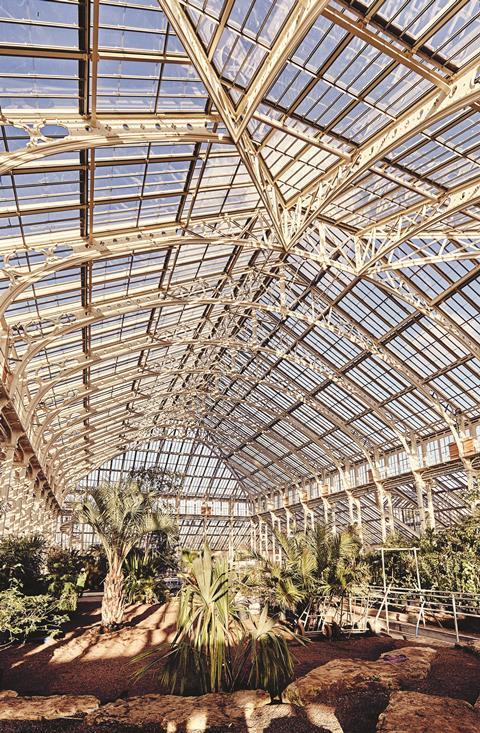

The Temperate House at Kew, the worldÔÇÖs largest Victorian greenhouse, is about to emerge from a painstaking ÔÇô and at times nerve-racking ÔÇô restoration, which included the replacement of every one of its 67,000 panes of glass

Renovating the worldÔÇÖs largest surviving Victorian glass structure may seem like a daunting enough task. But when that structure also happens to be a grade I listed building, is located on one of LondonÔÇÖs four Unesco world heritage sites and maintains only one vehicular access route ÔÇô which, with very few exceptions, is reserved solely for use by the Queen ÔÇô then it becomes clear that this is a project facing a formidable set of challenges.

Which is why the imminent completion of the Temperate House in Kew Gardens is a historic event. Covering 300 acres and opened in 1759, Kew Gardens in south-west London is one of the oldest and largest botanical gardens in the world. While its world-renowned collection of plants and specimens obviously takes centre stage, architecturally it is also famed for its string of palatial glass greenhouses, which date primarily from the 19th century.

The crystalline hump of the Palm House is probably the most famous of these, but at twice its size the Temperate House is by far the biggest. Designed by renowned neo-classicist Decimus Burton and built between 1860 and 1898, the stupendous glasshouse covers 4,880m┬▓, is 19m high at its tallest point and is 180m long, roughly the length of the main facade of SelfridgeÔÇÖs store in central London. Unlike the Palm House, the Temperate House has a masonry ground floor faced in ornamental stucco, from which a series of vast, glass-covered pitched roofs rise. The glass and masonry envelope conceals a cast-iron and cast-steel frame.

Water damage

For the past five years the building has been closed for a massive ┬ú41m renovation project set to fully complete this spring. The works were deemed necessary due to the deteriorating condition of the building fabric over recent years. Severe water damage was the biggest problem, with overflowing gutters and poor cill details on the buildingÔÇÖs thousands of windows leading to high levels of water ingress and the corrosion of much of the buildingÔÇÖs profuse ornamentation, which includes rooftop urns and statuary made from lead and marble. Inside, problems were compounded by an inadequate, inefficient heating and ventilation system, and the limited number of opening windows ÔÇô which are controlled by means of an antiquated hydraulic winder mechanism.

The buildingÔÇÖs last major refurbishment ÔÇô and the only one that had ever taken place before the current project ÔÇô was carried out in the 1970s. Its biggest legacy was the replacement of the original Victorian timber window frames with aluminium across the entire vast roof and the installation of a new heating and ventilation system. But none of this was enough to prevent the building being placed on Historic EnglandÔÇÖs Heritage at Risk register in 2012, a move that finally spurred KewÔÇÖs executive board to act.

The ambitious renovation subsequently implemented includes a host of improvements designed, according to KewÔÇÖs director of estates and capital development, Andrew Williams, ÔÇťto keep the building fabric in a decent state for around another 50 yearsÔÇŁ. The building is served by a new power supply from a biomass energy centre.

Improved amenities for staff and visitors have been provided, including a kitchen and, for the first time, toilets. Heating and ventilation have been completely overhauled, with a sophisticated new building management system installed and fully openable roof and clerestory windows now controlled by automated actuators. And while the greenhouse was formerly home to about 500 plants, new soil beds and pathway routes mean the revamped conservatory will accommodate 20 times that number.

But perhaps most impressively of all, every single piece of glass across the entire building has been replaced. This numbered some 67,000 individual panes of glass, the combined weight of which was a staggering 57 tonnes.

In many ways it was the glass that set the terms for the entire project. ÔÇťIt was the biggest single challenge,ÔÇŁ explains ISG senior project manager John Hatton. ÔÇťInitially, we planned to retain and restore the existing glass. As well as the new aluminium frame, all the glass was replaced in the 1970s, so even though much of it was in poor condition, it was already relatively modern. Plus, our overriding ambition was to retain as much of the existing fabric as possible ÔÇô ironically, even the 1970s aluminium frame and glazing is listed.

ÔÇťBut in the end we decided that removing, cleaning and restoring each pane would be complex, time-consuming and prohibitive. And there was also another very practical concern we had: no matter how much care and precision we took in handling the glass, it was inevitable that during the removal and restoration process, some of them would simply break.ÔÇŁ

So in the end it was decided to replace all the glass throughout the building. The new glass is virtually an exact match to the old one, surprisingly low-tech and untreated 4mm-thick agricultural glazing, a type of glass commonly used in greenhouses. ÔÇťBeyond letting in daylight, the glass here doesnÔÇÖt need to work that hard,ÔÇŁ explains Williams, ÔÇťunlike the Palm House, which mimics warm and humid tropical conditions, as the name suggests the Temperate House has a cooler temperature where retention of heat is not a priority. Plus, itÔÇÖs the new heating and ventilation system rather than the glass itself thatÔÇÖs chiefly responsible for controlling the climate inside the building.ÔÇŁ

The loneliest tree

But before any of the glass could be replaced a complex logistical plan had to swing into action. First, the vast majority of the greenhouseÔÇÖs plants were removed and stored in nearby temporary accommodation. One of these included the famous 250-year-old encephalartos woodii, something of a minor celebrity in Kew due to its status as being the only example of its species left on Earth. With admirable understatement Williams describes the delicate process of moving it as ÔÇťslightly nerve-racking.ÔÇŁ Nine trees too large to move remained in situ, each one protected by its own personal scaffold tower equipped with temporary heating and ventilation and a climactic sensor system.

Next the conservatoryÔÇÖs entire structure was tested, surveyed and photographed, with all components electronically tagged and positions carefully recorded. As King explains, the subsequent stage arguably proved the most arduous: scaffolding. ÔÇťTo reach all the glass we had to use internal scaffolding. But as this is a listed building the scaffolding had to be entirely structurally independent and not in any way transfer any loads onto the building fabric. To put it frankly, this was a huge challenge.ÔÇŁ

But the result was almost as spectacular as the Temperate House itself. Two linked but structurally independent scaffolds were built, an external one shrouded in a protective tent and an internal birdcage scaffold that sculpturally snaked its way up the inside face of the glass roof. Each scaffold was tied to the other through ground-level windows (with the windows first removed) to form a giant and tortuously intricate freestanding scaffold structure. The boards and tubing required to construct the scaffolding in its entirety would cover roughly 220 miles, just shy of the length of BritainÔÇÖs longest motorway, the M6.

Once the scaffold was up, the glass and aluminium could be removed. While the glass was replaced, the aluminium, which was also found to be in reasonably good condition, was given a gentle steam clean. As King explains, the removal of the glass and frame proved to be another nerve-racking process. ÔÇťWhen this happened the building was essentially left as an exposed skeletal cage. With the framing to help stabilise it, we were worried the building would be subject to deflection. But this wasnÔÇÖt the case at all; the cast-iron and cast-steel frame proved to be in remarkably good shape and throughout the process underwent virtually no movement at all.ÔÇŁ

║├╔ź¤╚╔˙TV systems

While the frame and windows were absent, the aforementioned iron and steel structure was grit-blasted and repainted. Concurrently, down below, the new mechanical and electrical apparatus was being installed. This included building management system actuators, new radiators, low-level apron vents and a new central services trench for drainage and pipework. Back underneath the roof, new servicing ductwork is discreetly threaded through the decorative cross-bracing of selected beams.

The process drew to a close with the reinstallation of the aluminium frame and the insertion of new glazing and windows. A new inclined cill detail was also used on all windows throughout the building: a logical improvement on the 1970s flat cill design that was responsible for directing so much water back into the building fabric. Prevention of water ingress is also the strategy employed on the roof, where a sophisticated network of new gulleys and lead flashing is designed to divert as much water away from the glass and masonry as possible.

As with so many restoration projects, externally, beyond a lick of paint and some rigorous cleaning, the building looks pretty much as it did before. But it has been thoroughly rejuvenated by a sensitive yet determined overhaul that has updated its services and fabric while preserving its all-important historic structure and botanical function. This delicate feat is perhaps most evident in the meticulous renewal of the buildingÔÇÖs spectacular glass skin. For obvious reasons, Kew considers its incomparable wealth of plants to be the star of the show. But it is the care and ingenuity revealed in the restoration of precious built assets like the Temperate House that enable the show to go on.

Project Team

Client: Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

Restoration architect: Donald Insall Associates

Main contractor: ISG

Structural engineer: Ramboll UK

QS: Turner & Townsend

No comments yet