An eagerly awaited luxury housing development at KingÔÇÖs Cross has an unusual exterior ÔÇô three Victorian gasholders frame the structures. Ike Ijeh looks at whether the scheme can successfully combine its industrial history with contemporary design

There is something bewitching about gasholders. We are used to energy being everywhere but invisible ÔÇô the gas, heat and electricity that powers our lives is constantly hurtling unseen through hidden pipes and wires ÔÇô summoned only by the flick of a switch or push of a button.

But gasholders give energy a physical form, inarticulate matter improbably corralled into a man-made object, like a ghost captured on film. The fact these structures once appeared in contrasting domestic settings, swollen drums of industry looming above terraced rooftops and cobbled streets, merely added to their allure.

But of course gasholders are now almost a thing of the past. For the best part of 200 years they were a recognisable feature of the British landscape, storing ÔÇťtownÔÇŁ gas created by burning coal in giant pressurised drums that would rise up and down depending on the volume of gas. But today the vast majority have been dismantled, victims of spiralling urban property prices and the pipelines that now funnel natural gas from the North Sea.

However, although their function is now largely obsolete, some remain. One of the most famous is the collection of gasholders at LondonÔÇÖs KingÔÇÖs Cross. The Pancras Gasworks were built in the 1850s and were the largest gasworks in the capital, once holding 1.1 million ft3 of ÔÇťtownÔÇŁ gas in a group of a dozen gasholders up to 25m high. But in 2000 the gasworks were decommissioned, before being dismantled the following year to allow for the construction of the new Channel Tunnel Rail Link underneath.

However, four of the gasholders were incorporated into ArgentÔÇÖs masterplan for the 67ha KingÔÇÖs Cross Central regeneration and were shipped to specialist engineers in Yorkshire for restoration. Each of 123 columns that comprise the gas holders weighs eight to 10 tonnes. In 2013, they were returned to their new location on the KingÔÇÖs Cross site for the painstaking process of piece by piece reassembly. The biggest, Gasholder No. 8, opened as an urban park in 2015 by means of an imaginative pavilion and landscaping installation by Bell Phillips Architects.

Roundhouses

But now Gasholders No. 10, 11 and 12, which sit beside it, have been ingeniously reconfigured as housing. Designed by Wilkinson Eyre Architects using a watchmaker theme, 144 residential units sit within three cylindrical blocks of flats entirely enclosed by the restored gasholder frames. Together, they form one of the highlights of the masterplan and are arguably the most eagerly anticipated project of the entire KingÔÇÖs Cross redevelopment.

Unlikely as it may seem, the KingÔÇÖs Cross gasholders are not the first to be converted into housing. OMP Architects insensitively slotted in 240 glazed flats to DublinÔÇÖs Gasworks scheme in 2006. And five years earlier, a quartet of prominent architects including Jean Nouvel and Coop Himmelblau converted four 1896 Gasometers in Simmering, Vienna, into flats and offices (pictured overleaf). However, these differ from KingÔÇÖs Cross because they are enclosed behind ornate original brick facades as opposed to the cast-iron steel columns and girders that form a metal girdle around Gasholders 10 to 12.

The Simmering gasholders are four entirely separate structures. But at KingÔÇÖs Cross, the three gasholders are conjoined to form an overlapping trio of cylinders, in a gesture of mechanistic whimsy. These are locally referred to as the ÔÇťSiamese TripletsÔÇŁ and this unusual configuration helped earn the gasholders their grade II listing and their place in the KingÔÇÖs Cross masterplan.

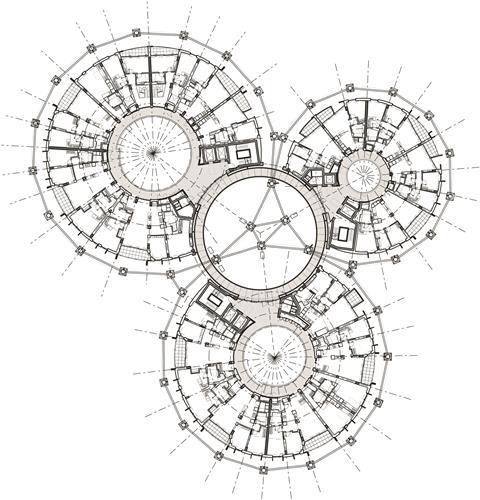

The new scheme sees three separate but interlinked circular blocks of flats ÔÇô one built within each gas holder cylinder. The blocks are eight, nine and 12 storeys high ÔÇô the differing heights reflecting the fact that the tanks the gasholders once contained would rise up and down depending on the amount of gas within them. The staggered heights are also indicative of the varying diameters each gasholder spans, with the largest measuring 40m.

Beyond the veil

Critically, the structure of the new buildings is entirely independent from the structure of the gasholders themselves, with no load whatsoever being transferred on to the listed frame. However, the 1,500mm-high holding down bolts at the base of the Victorian cast-iron columns are anchored to the ground-floor slab. Each building is faced in dark grey aluminium panels punctuated by windows and recessed balconies. Furthermore, the entire facade is concealed behind perforated aluminium shutters that can be automatically controlled by individual flats to either fully retract or extend across the entire envelope like a metallic veil.

For Wilkinson Eyre co-founder Chris Wilkinson, this ÔÇťveilÔÇŁ was a critical component in channelling the buildingÔÇÖs industrial roots. ÔÇťItÔÇÖs a listed structure and it was very important to us to maintain its industrial identity,ÔÇŁ he says.

ÔÇťMaterially, the aluminium recalls the cast iron of the columns and girders. But the opening veil ensures that the facade never stays the same ÔÇô it is always active and dynamic in the same way that the gasholders were when the tanks would move up and down.ÔÇŁ This, says Wilkinson, drove the decision not to vertically stack the facade, aligning windows and doors directly above one another: ÔÇťBalconies, doors and windows are all in different places to enhance this idea of movement.ÔÇŁ

As a central architectural conceit for both building and elevations, WilkinsonÔÇÖs aims are convincingly realised. The differing building heights are a particularly masterful touch ÔÇô with the trio of rooflines oscillating either below or above the top of the gasholders like pipes on an organ, the historic girders are rightly shown to be a frame rather than an enveloping the housing.

Another wise move was not stacking the composition of the facade in accordance with the position of the historic columns and girders, as Wilkinson mentions. This not only avoids the monumental and unnecessary headache of trying to conform flat layouts and elevations to a 19th-century industrial cage but also reveals the structural autonomy the new buildings pursue.

The changing ÔÇťveilÔÇŁ of shutters also creates mechanised, randomised movement that pays homage to the rise and fall of the tanks from yesteryear. In collusion with the impervious frame, it offers a touch of the genial disorder that sparks life in residential buildings and distinguishes them from their commercial counterparts.

A view to remember

There is no such disorder inside, though. The Gasholders is KingÔÇÖs Cross CentralÔÇÖs most exclusive luxury residential offer, with studios starting at ┬ú810,000. Once you breach the single entrance, you are plunged into a plush world of brass fittings, bronze trims, polished floors and decadent veneers.

The scheme comes with all the customary accoutrements associated with LondonÔÇÖs high-end residential market including screening room, spa, gym, pool, sauna, conference room, and lounge, available for temporary hire by pampered occupants at the touch of an iPad screen. As one would expect, the flats follow the same theme of quiet ostentation, with granite kitchens, walk-in wardrobes and master en-suite bathrooms de rigueur. The floorplan is radial with party walls extending from the centre of the circles like bicycle spokes in a wheel. Therefore, each flat roughly assumes a pie-chart segment plan but due to large circumference of the drums, rooms still feel broadly rectilinear.

To put it bluntly, these days many luxury flats could be anywhere in London and most conform to the same aesthetic palette. What is so often missing is charisma, but here this comes from the views of the historic frame outside. The frame is generally positioned up to 3m away from exterior walls ÔÇô enough space to allow for generous balconies but more importantly, to allow for a glimpsed view of whatever part of the columns or girders are visible without the frame interrupting the view of London beyond.

This allows an infinite number of new appreciations of the Victorian structure, throughout the building, with the view from each room the key distinguishing feature amid the sea of identikit indulgence that swamps the interiors.

The lavish interior decoration inside the building reveals its second driving concept: watchmaking. ÔÇťI liked the idea of precious internal mechanisms,ÔÇŁ Wilkinson says. ÔÇťIt was a nice counterfoil to the industrial theme.ÔÇŁ

It is refreshing to have a prominent architect reveal that his architecture has not been driven by a theoretical agenda applied to any given site, but simply by something he likes.

Architecture is far more a product of personality than it is of principle and it would be welcome if more architects were willing to admit that. In this instance, the theme of a watch fits well with the form of a circular building and is subtly expressed through the interiors in features such as the radial segmentation of floor patterns to the scalloped edges of the atriums.

There are three full-height atriums, funnelled into the centre of each drum and lined with balconies from which the flats can be reached and which are themselves served by off-centre stair and lift coves. Swirling upwards towards oculus rooflights and trimmed with art deco-lite detailing such as chevron lamps and grooved edges, these are sparse yet vivid spaces that mark a significant shift from the industrial exterior.

Circles within circles

Most dramatic of all is the fourth atrium, created right in the middle of the scheme, which is treated as an open courtyard. This also contains the phalanx of columns and girders where all three gasholders join. Here, once again industrial Victoriana takes centre stage, with the historic frame crashing into the space. Closer inspection reveals the richness of decoration applied to its columns and girder structure.

This central atrium is encircled by a series of high-level glass walkways that wrap around the inner edges of the buildings and link all three atriums. The top walkway also provides access to the decked communal roof garden located on lowest of the three blocks.

Crucially, the space provides the chance to see Wilkinson EyreÔÇÖs fulsome approach to heritage. Wilkinson readily acknowledges the practiceÔÇÖs reputation for engineering-driven design but passionately maintains that ÔÇťheritage and technology, old and new, can work well togetherÔÇŁ. And here, as in the architectÔÇÖs monumental Weston Library in Oxford, we see the practice employing engineering prowess to bridge the gap between the two.

In this central atrium, the prowess may primarily come in the form of the old, with the plunging Victorian columns dominating. But the architectural decision to treat the new, in the form of the balconies and inner rotunda walls, as a paler backdrop still marks a well judged awareness of the core engineering components that are driving the drama and animation of the space. In many ways, it makes for a more convincing consolidation than the exterior which, stripped of its cast-iron girdle, would probably veer towards grey and metallic corporate anonymity. But perhaps this is the point ÔÇô the antique gasholders should be the star of the show and by and large, the new additions are restrained enough to let it do just that.

Project Team

Client: Argent

Architect: Wilkinson Eyre

Interior architect: Jonathan Tuckey Design

Main contractor: Carillion

Structural and fa├žade engineer: Arup

Groundworks: Morrisroe

No comments yet