Despite the credit crunch putting the boot in to the market, there are still chances going begging in the stadium sector â itâs just a little harder to score âŠ

In August, as Liverpoolâs international cast of multimillion-pound football stars prepared to kick off the new season, work on the clubâs new stadium ground to a halt. The cause? Lack of funding. The club said the scheme had been affected by âglobal market conditionsâ.

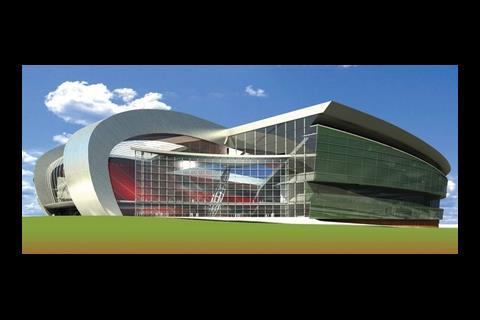

If the news sent a jolt of panic through the stadium-building market, which has seen grand new arenas rise from Southampton to Sunderland over the past decade on the back of lucrative sponsorship deals and foreign investment, then events in Manchester a couple of weeks later may have confused the picture further. The acquisition of Manchester City by the Abu Dhabi government shows that the super-wealthy are still drawn to British football. So is the market for new stadiums still full of Champions League potential or is it heading to the bottom of the Conference?

What the pundits say

The opinions of the experts are mixed.

Mark Roberts, a senior consultant at Deloitte, believes the stadium sector will remain buoyant, because clubs will still be able to fund a new ground by selling the old one. âDespite market conditions, some opportunities are too good to pass up for developers. On a macro level you can say itâs a challenging market, but on a micro level obviously some sites are very valuable.â

Barry Winterton, head of the sports and leisure team at Franklin + Andrews, is not so sure: âItâs becoming increasingly difficult for clubs to sell their grounds, as developers are unwilling to speculate,â he says. But he does think there is potential for deals where a club teams up with a developer, with the developer including the construction of a stadium as a way of winning planning permission for a wider development. A classic example is Tesco and Evertonâs tie-up. âThe local authority is still weighing up the scheme,â says Winterton, âbut Tesco has a much better chance of getting it through with Everton on board because thereâs a community benefit.â

And there is still one overriding factor driving stadium-building: many big clubs are simply desperate to upgrade. The dream is to copy Arsenal, which doubled its match-day revenues in the first season at the new Emirates stadium. The club made ÂŁ90.6m over the season, or ÂŁ3.1m per game.

Portsmouth is among those hoping to âdo an Arsenalâ. The club is working with Sellar Property Group on plans to move to a new ÂŁ100m home at Horsea Island by the start of the 2011/12 season. Director Roberto Avondo says the club simply has to move: âFratton Park is 100 years old, and showing its age. We donât have the facilities we would like â itâs fundamentally a football stadium and not much else. If you look at the Emirates, itâs much more than an arena for football.â

Actual ticket sales can now account for as little as 30% of a clubâs overall revenue, so clubs want to create a venue that will make visitors spend more money.

Avondo says: âOur fans come to Fratton Park a couple of hours before the game, but I think it could easily become an all-day experience at the new stadium. The time before and after the game will be an opportunity to enjoy the retail and leisure facilities. There will be facilities for the entire family.â

And of course for the much-needed wealthier guests, too. Chris Lee, head of professional sport at Barclays, points out that Evertonâs current stadium, for example, has very little in the way of corporate boxes. âBuild a new ground and they can include premium seating - the income they will get is hugely increased. Arsenal charges ÂŁ12,000 to hire a box for a big game.

âImproving other facilities can help, too. People donât tend to spend very much if theyâre queuing outside the gentsâ toilets for all 15 minutes of half time.â

Grinding out a result

But despite enduring demand, thereâs no doubt itâs going to be tougher to win and pull off a stadium project than has been the case in the recent past. Winterton warns that funders are now much stricter about lending money to football clubs. âThe bank is going to scrutinise your project much more closely now. They will want a guaranteed return on their investment.â

Look at Leeds. They were right up there, but a few years later theyâre struggling to survive. Banks want certainty

Barry Winterton, Franklin + Andrews

Extra pressure will come from the fact that football is already seen as a volatile area. âLook at Leeds. They were right up there in the Premier League but two or three years later theyâre struggling to survive. If you are a bank, you want certainty.â

Barclaysâ Lee says that banks are also wary of the possible damage to their reputation should they have to repossess a stadium. In other words, the clubâs fans would turn against the bank. It means that banks do extra-thorough due diligence on stadium schemes.

With stadium projects under pressure to eke out every last opportunity for revenue-making, increasingly building work will be going way beyond creating an arena for football. Lee says that the project completed by Coventry City is the sort of scheme that the banks like to see. âThe 32,500-capacity stadium has a concert venue attached to it, a ÂŁ40m casino, 75-bedroom hotel, an upmarket gym, and a 2,000-capacity banqueting suite.â

Itâs certainly not just about football any more.

Getting in the starting line-up

According to Portsmouthâs Avondo, winning work in this sector, is all about big-match experience. He says: âWeâd want our contractors to have a proven track record.â

Martin Jennings, partner at David Langdon, the project manager for Liverpoolâs new stadium, agrees: âThe complexity of actually building these structures is immense. Thereâs a lot of pre-cast concrete, a lot of steelwork and normally a complex cantilever roof, so that there are no columns to obstruct sightlines.â The number of contractors in the UK who can deliver a structure of that scale is relatively small, he says. âStadiums are very complex things to design and build, and that has caught people out in the past.â

Winterton says you must also be willing to work flexibly: âEvery stadium is unique, and different groups of fans want different things. Youâve got to understand your target market and develop something around that.â

Once the work has begun, cost management is paramount. Stadium projects are big and complex, so controlling the budget has always been tough (Wembley, anyone?). Christopher Lee, senior principal at HOK Sport and design director for Arsenalâs Emirates stadium, says: âVirtually anything can go wrong with stadiums because theyâre massive projects with massive teams. We occasionally see someone miscalculate the cost of a toilet, which is a minor mistake, but then of course itâs multiplied by 3,000.â

A team game

As well as working flexibly and to budget, everyone on the project team must be ready to work with public sector partners. Speaking of his experience on the Emirates stadium, HOK Sportâs Lee says: âWe worked very closely with the local authority in Islington, the Greater London Authority and Ken Livingstone himself (then London mayor). It was a remarkable partnership.â

Jennings adds that football clubs are unique clients to work with. âThe management structure at a club tends to be quite tight, and the people you deal with are very down to earth. Generally theyâre not bureaucratic, theyâre straightforward, and theyâre good people to work with.â

And youâll have to please more people than just the client. Lee says that stadium construction engages people like little else. So be prepared for âmultiple inputs from separate client bodies, plus supporters, and the taxi driver who tells you how he thinks the stadium should beâ.

On the plus side, you wonât struggle to find staff to work on the scheme. Jennings says: âWe tend to find we get a lot of volunteers for any new stadium work because theyâre fans. Football inspires great loyalty.â

No comments yet