Despite signs of economic recovery, the scale of homelessness in the UK is undiminished. In fact, a combination of changes to the benefits system and funding cuts to charities means the outlook for the most excluded in society looks even more uncertain

Martin is perhaps not the type of person you would typically think of as someone who could end up homeless. Born in Cambridge and in school until he was 18, he spent six years in the army before moving back home and getting a job in a security firm. But suddenly the business went bust.

ŌĆ£That was the first time I found myself with no job, and nowhere to stay,ŌĆØ says Martin, who turned to a life of alcohol and sleeping on the streets. ŌĆ£I think itŌĆÖs important that people realise I had a decent life to start off with. When I lived on the streets I felt like people thought I was a piece of dirt, but they should know that bad luck can happen to anyone.ŌĆØ

With UK unemployment reaching 8.5% at the height of the recession, stories such as MartinŌĆÖs have in fact become all too familiar. Statistics indicate that all forms of homelessness have risen throughout the economic downturn as, for some, a sudden lack of income or difficulty maintaining employment in a tough jobs market left them unable to meet rent or mortgage payments. The economic picture has compounded other factors that remain major causes of homelessness: relationship breakdowns, drug and alcohol problems, and mental health difficulties.

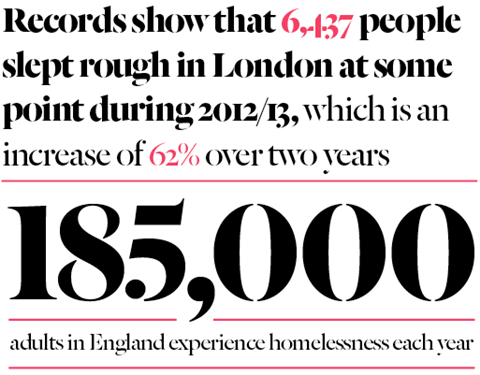

There is some evidence to suggest that the growth in homelessness is slowing as economic recovery begins - government figures for Q3 in 2013 showed 3% fewer homeless households in England applied to local authorities for help than the same time a year earlier. However, research by Crisis and the Joseph Rowntree Foundation published in December 2013 suggests 185,000 adults in England experience some form of homelessness each year, putting homelessness at a three-year high. Although overall unemployment may be turning for the better, there are other contributory factors to homelessness that appear to be worsening. These include an increased risk of eviction from private-rented accommodation by landlords, and potentially even social landlords, because of changes in housing benefit.

For those already in a cycle of homelessness, and those on the cusp, this presents a worrying new reality at a time when homelessness may have been expected to decrease; particularly given that cuts to charitiesŌĆÖ income have led to a sharp drop in the amount of facilities and services available to help people back off the streets.

The scale of homelessness

Knowing exactly how many people are homeless is impossible, but the picture has certainly worsened dramatically during the recession. In 2012-13, the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG) recorded that the number of households in England that approached their council asking for help due to homelessness was 113,260, an 11% rise over two years. Typically just under half of these applications are accepted by local authorities as being statutorily homeless, meaning the authority has a duty to house them; the number accepted as ŌĆ£statutory homelessŌĆØ - which includes people with dependents, vulnerable single adults and pregnant women - was 53,540 in 2012-13.

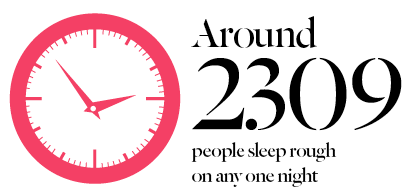

Meanwhile, in 2012 a government estimate based on street counts put the number of people sleeping rough on any one night at about 2,309, a rise of 31% over two years. In London alone, the homelessness database CHAIN records that 6,437 people slept rough at some point during 2012/13, which was an increase of 62% over two years. Many homelessness charities believe the number of rough sleepers is actually much higher than these estimates, as the transitory nature of those affected makes it difficult to get an accurate picture of the situation.

With unemployment a major contributory factor to homelessness, these trends, while alarming, are to some extent not surprising against a backdrop of economic downturn. And there is, encouragingly, some suggestion that the situation is stabilising as the economy picks up. Figures released by DCLG for the third quarter of 2013 showed that 28,380 households applied to councils for help with homelessness, a 3% drop on the same period in 2012. Of these, 13,330 were accepted as being ŌĆ£statutory homelessŌĆØ and ŌĆ£in priority needŌĆØ - a 4% decrease on the previous year.

This improvement, however, has not been felt everywhere. In London, there was a 2% increase in applications to local authorities, and a 13% increase in acceptances. The South-east also saw a 9% increase in applications, with the number of acceptances remaining unchanged.

A complex and changing pattern

The reasons that a person can become homeless are numerous and often interwoven with each other: for many, there is no single reason they find themselves on the streets. Drug and alcohol problems, often assumed by many to be the cause of homelessness, were cited as a contributory factor by 31% and 28% of homeless people in a wide ranging survey by Shelter published in 2007, but a far higher proportion (41%) gave the breakdown of a relationship as a factor.

Mary, a ŌĆ£companionŌĆØ at Emmaus Hastings - the term used for the former homeless people who live and work in communities run by Emmaus- is one such person. She met her first partner in her late 20s, and had a 13-year relationship in which they had three children, while she worked a succession of part-time jobs. After the relationship ended, she says, she began another with ŌĆ£an old friendŌĆØ, moving her family in with him. ŌĆ£After 10 years that relationship broke down and I left,ŌĆØ says Mary. ŌĆ£I walked out of the house and went to stay with my son and daughter-in-law. But I couldnŌĆÖt do that forever.ŌĆØ

In MaryŌĆÖs case, her local housing trust suggested that she looked into living at Emmaus Brighton, making her aware of the national organisation that runs the community that is now her home. For others, such as Karen, an Emmaus companion at Preston, the impact of a failed relationship can take even longer to recover from - and lead to more problems that fuel a cycle of homelessness.

Karen describes how having an ŌĆ£abusive and controlling partnerŌĆØ in her teens, with whom she had three children, contributed to her joining him in using heroin, stealing to pay for her addiction. It was only when her partner died, aged 31, of complications related to his own addiction that she was able to free herself of the drug, eventually moving to Emmaus from a bail hostel after serving an

eight-month spell in prison.

Leaving prison is a well-known catalyst for homelessness, with 25% of those questioned in ShelterŌĆÖs 2007 survey citing it as a factor. But another, again bigger trigger, which is often overlooked, is people being asked to leave their

family home.

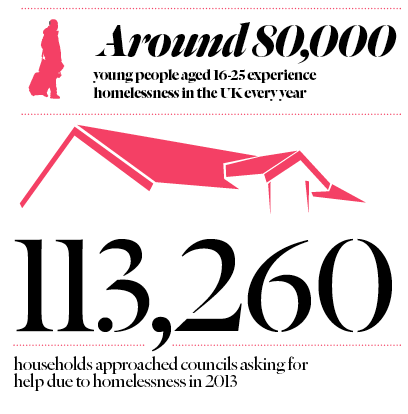

Between October 2012 and September 2013, government figures show that 15,680 households headed by people under 25 were accepted as statutory homeless in England. Research by charity Centrepoint in 2011 estimated that 80,000 young people experience some form of homelessness in the UK every year. A survey of 169 frontline agencies, called Young and Homeless 2013, found that of those young people who approached local authorities for help, almost half (44%) said that their parents were no longer willing to accommodate them, with a further 14% saying a friend or relative was no longer willing.

Campaigners against homelessness are concerned that young people would be even more at risk if current suggestions from the Conservative party to restrict housing benefit for under 25-year-olds become law. The party has announced it is reviewing benefit entitlements for 16-25-year-olds ahead of its manifesto for the next election, and David Cameron has previously suggested that changes could entail an end to automatic entitlement to housing benefits for those aged under 25 who meet all other eligibility criteria.

Rick Henderson, chief executive of Homeless Link, says: ŌĆ£A severe shortage of affordable housing and the highest levels of youth unemployment in nearly 20 years mean many young people face significant barriers to achieving their goals. We are calling on the government to invest in their futures by ensuring the support is in place to make sure they have somewhere safe to call home.ŌĆØ

Another change to housing benefit which already appears to be worsening the problem of homelessness is the move to pay benefit direct to claimaints, rather than to their landlords as has historically been the case. Since 2008, the majority of benefit claimants who rent from private landlords have their housing benefit paid direct to them to pass on as rent, which the National Landlords Association has said has led some private landlords to refuse to take claimants on benefit as they no longer have the security of receiving tenantsŌĆÖ rent payments direct from government. The proportion of households accepted as ŌĆ£statutory homelessŌĆØ as a result of the loss of private tenancies rose to 27% of all cases by Q1 2013-14, according to DCLG figures.

Now, the move away from paying benefits direct to landlords is being broadened into the social housing sector as a central strand of the governmentŌĆÖs Universal Credit policy. This will result in six forms of benefit, including housing benefit, being paid as one sum direct to the claimant.

The programme, which has been mired in technical difficulties, is due to be rolled out by 2017 but is currently only being enacted on a very limited basis. However, six pilot schemes launched in 2011 have led to significant rises in rent arrears. Tenants in Torfaen, South Wales, one of the pilot areas, saw rent arrears rise sevenfold in the first seven months of the pilot, according to a BBC investigation. Social landlords have expressed deep concern over the increased risk that tenants will end up spending the benefit elsewhere, leaving them at risk of eviction.

The increased risk to payments to social landlords has also caused significant concern from the landlords as they fear it will affect their future revenue streams, both directly and in the sense that it will make banks less willing to lend to them. This, in turn, has led to warnings that they will have to scale back social housing build programmes and community initiatives designed to help people back into employment or training.

A final element in this dangerous stacking of odds against those struggling to avoid homelessness is cuts experienced by local authorities and charities, including those in the homeless sector, as a result of recession. Homeless LinkŌĆÖs 2013 survey of homelessness services in England reports a 9% reduction in bed spaces since 2010, with over half (55%) refusing clients because their needs were too high to be met on the resource available. Many of these beds, including those in projects supported by CRASH, offer help to single homeless people aged over 18, a group who are not entitled to any statutory assistance from local authorities.

So the economy may well be on the mend, but for those trying to help some of its most excluded people rejoin society, the task may be becoming harder rather than easier.

No comments yet