With a focus on innovation and access, the east London studio is leading the charge in the architectural education revolution. Ben Flatman reports on how they are helping a new generation of architects to design the cities of tomorrow

Architects operate within a fast-changing industry, with constant pressure to deliver more for less. At the same time, societal changes are requiring the profession to focus increasingly on access, with expectations that employers provide opportunities to people who might previously never have considered a career in architecture.

How should architects respond? And how far can a single practice go in actively addressing the huge range of demands to deliver faster, better, and more diverse outcomes for clients and staff?

Founded in 2016, Ackroyd Lowrie has developed a reputation for delivering thoughtful, people-centred architecture that prioritises sustainability. The work spans a range of sectors, from residential developments and neighbourhood masterplans to commercial spaces and educational facilities. The practice is also branching out into property development, with a major housing scheme recently approved in Harlow.

Leading the practice are Jon Ackroyd and Oliver Lowrie, who bring substantial experience and a shared commitment to innovation and outreach. The two met while working together at Architype, a practice widely recognised for its commitment to Passivhaus standards and net zero.

“Sustainability is built in thanks to our background,” explains Lowrie, “but when we set up on our own, we also wanted to think differently. And so, innovation is really core to what we do.”

The company is highly focused on the future of the profession and how practices can equip themselves and their staff with the skills and resilience to thrive. Their approach emphasises the thoughtful integration of technology into the practice, including using Virtual Reality visualisations to engage with clients and stakeholders effectively.

Training architects to design the cities of the future

But the focus on innovation and future-planning also embraces access and providing opportunities to a younger generation of architects. One of their proudest achievements is the creation of their own in-house education and training programme, designed to help 16 to 18-year-olds access careers in architecture, and build vital workplace skills. It is called the AL Academy, and works in close collaboration with the New City College (NCC) group.

“The academy is all about thinking differently about how we bring people into the industry,” says Ackroyd, who underlines the practice’s forward-looking philosophy as a key driver behind the initiative. “The decision to set it up was very specifically because our top line is that we want to build a company to design the cities of the future. That’s our guiding North Star.”

“We realised that all of our other policies needed to feed into that,” adds Lowrie, who traces the academy’s creation back to the early days after the covid lockdowns had finally been lifted. “We’d had a session in the studio with some students from the London School of Architecture and, through that discussion, we were really challenged to question what we meant by ‘cities of the future’.

“We had this revelation that surely, as a profession, we should be looking at how we can bring people that have got lived experience of this city into the industry, which architecture doesn’t tend to do.”

An awareness of the growing cost of architectural education, and how this was becoming a massive barrier to entry, was also a key motivation. “We also sort of like disrupting things,” says Lowrie.

“I got away with £20,000 worth of debt as a student. But, with architectural education, students are now coming out with £100,000 worth of debt. It’s just silly.

“We realised that we could train students so that they don’t spend a penny, and they get to become qualified architects. So that’s what drove it.”

Lowrie also cites Sir Alex Ferguson’s youth programme at Manchester United as an inspiration. “I watched this documentary about Alex Ferguson. He had all these pencil sketches of this ecosystem of recruitment he wanted to create.

“Beckham, Neville and Nicky Butt, they all came through the Manchester United academy. So we’ve kind of stolen his idea,” he says.

“We want these kids to be the next generation of architects. We want to take them on a 10-year journey to becoming fully qualified architects.”

Full-time architectural education is losing its appeal

Both are agreed that a full-time university education is no longer the great attraction for students or employers that it used to be. They emphasise the importance of workplace skills and believe the advice and coaching that they provide in the studio is giving the academy’s students what Lowrie believes will be “a huge advantage” over students who have spent five years in full-time university education. They, he believes, are often taught too little about what architects actually do.

Referencing Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,000-hour rule (the idea that it takes this amount of time to master any skill), Lowrie says the academy gives the students real workplace experience while they are studying. “These guys are going to be doing the 10,000 hours before they’re at the end of Part I. And full-time students aren’t getting that.”

Ackroyd and Lowrie were also clear that, as well as doing outreach and bringing in talented 16 to 18-year-old local young people, the practice, located close to the Regents Canal in Hackney, wanted to provide them with the opportunity to progress to full qualification as architects. So the AL Academy is specifically set up to allow them to transition from NCC’s BTEC in construction and the built environment course, which is a Level 3 qualification, equivalent to A-level, onto London South Bank University’s apprenticeship degree route to becoming a registered architect.

Although the practice makes it clear to students that a full-time university degree is definitely one of their options, the academy is geared towards supporting the apprenticeship route. Lowrie highlights the disjuncture between the tangible skills that employers need and the sometimes abstruse content of many university architecture courses.

As well as the growing levels of indebtedness among full-time students, he points to the way in which architecture schools often leave workplace skills to the end of the course – if they address them at all. “I left architecture school feeling like I knew very little about detailing,” says Lowrie, by way of example. The hope is that the academy’s students will leave with much more knowledge under their belts.

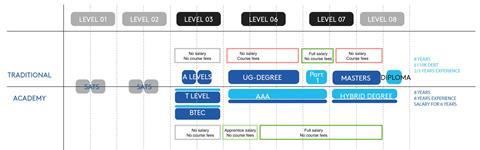

Ackroyd and Lowrie – obsessive about detail and with an insatiable appetite for getting to the root of a problem – mapped out the learning and earning trajectories of a full-time, university-educated architecture student and what they believed was possible under their scheme. Their projections show full-time students racking up debt at a terrifying rate, while their AL Academy route, which sees students earning from age 18 and throughout their training, culminates with qualification as a registered architect at approximately the same time it takes full-time students.

This means around eight years of post-18 training at the AL Academy, as opposed to the possible seven (in reality an average of nine and a half) years that it takes most full-time architecture students.

The education partner

The desire to connect the practice’s innovative recruitment and training vision with the latent talent and knowledge in the local community led to discussions with Hackney council about how to go about engaging with young people. Eventually, after a few false starts, they made contact with Jane Nugent, work experience and industry placement coordinator at NCC.

“None of it would have fallen into place without Jane,” says Ackroyd, who says the practice initially found it hard to find an education institution to partner with. “We tried lots of times to contact colleges, but until we found NCC, nobody was biting on the offer.”

“It’s very challenging to find placements for our students, especially within this industry,” says Nugent. “That’s why it’s been amazing working with what Oliver and Jon have done. Architecture was very much a closed book to NCC before.

“And, usually, the students on our BTEC construction course were much more interested in going on to be quantity surveyors, estimators, project managers, site managers. But now they are beginning to see that there are other avenues to go down.

“And that’s all because word gets around – because there’s someone else who has had that work experience at Ackroyd Lowrie. And, funnily enough, this year, we’ve already got more students that are looking at a route into architecture.”

The 16-18 programme

Joe Maguire is a project architect at Ackroyd Lowrie, but also leads on much of the AL Academy programme. This involves outreach visits to 14 to 16-year-olds at NCC’s campuses (the education group has five campuses across London and Essex), aimed at sparking interest in a career in architecture. He also helps to supervise the 16 to 18-year-olds when they are in the office.

“We go in and we do a workshop,” says Maguire of his work with the 14 to 16-year-olds. “It’s lots of fun and from that we usually get a couple of students expressing an interest.”

The AL Academy looks to recruit three students each year, with six students in total spending a total of 45 days each in the studio during their two-year period of study on the BTEC course (soon to become a T-Level as NCC transitions to the new vocational qualifications standard).

This allows Ackroyd Lowrie to rotate the students in and out, with usually no more than two working from the office at any given time, although all six are invited in for specific days of team bonding and design-focused exercises. Graphisoft has also donated two CAD licences to the academy, helping to keep down overheads for the practice.

On the day that BD visits, the entire group of six students are present, with Joe leading them in developing design ideas for a live small site close to the practice. All six students have been interviewed and selected by the AL Academy for their aptitude and because of their interest in pursuing a career in architecture.

“It’s all very self-selecting,” says Maguire. “They’ve chosen to be here and we want them because of their commitment.”

Lowrie admits that it has been a “massive learning curve” for all involved. “Sometimes they’ve never set foot in a workplace environment before, and they ask if they can go to the toilet and stuff like that. It’s quite sweet. But, you know, it doesn’t take long for them to adapt.

“We try and treat them like any other employee would be treated. So that includes making coffee badly and answering the phones,” he explains. “And we get them working on projects as much as we can. We just treat them normally.”

Case studies

Rasheikh Robinson has just completed the BTEC course at NCC and has accepted a place on the LSBU degree apprenticeship starting this September. Having previously tried his hand on a carpentry programme, Rasheikh decided to go back to NCC to complete his BTEC, which introduced him to the AL Academy.

His interest in architecture started at a young age. “I wanted to build bridges and design skyscrapers”, he explains. He was encouraged by his mother’s recollections of how his grandfather had worked on school projects in Jamaica as a QS.

Rasheikh will now work four days a week in the office as he progresses through the apprenticeship route and hopes to complete his architectural training at Ackroyd Lowrie over the next eight years.

Scarlett Gammons is a year behind Rasheikh on the AL Academy programme, but shares the same passion for architecture. Her interest was sparked by computer games, and was also encouraged by her mother, who saw the potential to put her virtual design skills to good use as a career.

“I used to play Minecraft as a kid,” she says. “That’s where it all stemmed from.”

Apprenticeships

Once the students have completed their BTEC course, usually at around 18, and assuming they are keen to continue, and are successful in getting onto the LSBU apprenticeship degree course, they can start working at Ackroyd Lowrie four days a week on an apprenticeship wage, which starts at £6.40 an hour but increases over time.

Because the practice’s apprentices already have two years’ experience in the studio, they are a known quantity. They also have relevant skills from day one, as well as that invaluable experience of workplace behaviours and culture that are so key to a successful career in any field.

Lowrie believes the apprenticeship route, with four days a week in the office and one day a week in a formal education setting, strikes the right balance. “The bit I hated the most about full-time education was going back to Part 2,” he says. “I was really enjoying my year out and then you have to go back to university and suddenly you’re skint again.

“Today, once they get to undergraduate degree level, students start to rack up debt,” he explains. “Whereas we will pay you.

“Our apprentices are starting on a low salary, but by the end of four years, they’ll be on the same salary as we would pay a recent Part 1 graduate, and they have had the advantage of earning while they learn throughout that whole time.”

Skilling up for a stronger future

Ackroyd Lowrie’s approach exemplifies how architectural practices can go beyond traditional boundaries, not just in design but in cultivating a new generation of architects. By integrating innovative training models like the AL Academy, they are setting a precedent for how firms can actively contribute to the profession’s evolution. This is not just about meeting industry demands – it’s about redefining them.

The success of their initiative speaks to the power of a forward-looking philosophy that values both diversity and real-world experience. As they continue to push the envelope in design and education, Ackroyd Lowrie is not just preparing for the future – they’re building it, one opportunity at a time.

This commitment to both innovation and inclusion is surely what will drive architecture forward in the years to come.

No comments yet