When designers began working on Defraâs offices in Alnwick, they thought a BREEAM âexcellentâ rating an exciting enough challenge. But then BRE went and introduced âoutstandingââŠ

For designers of green offices, itâs becoming increasingly difficult to stand out from the crowd. As legislation tightens and more clients demand low-energy buildings, separating one scheme from the next is getting a lot trickier. Itâs a problem that BRE acknowledged last year when it decided that too many buildings were achieving âexcellentâ under its BREEAM environmental rating scheme. So, after 18 years, it upped the ante by introducing an âoutstandingâ ranking that will push designers to aim even higher. And the building you see here could become the first to achieve that plaudit.

Defraâs new offices in Alnwick, Northumbria, were not always destined to become the low energy exemplar that they have. Known as the Zebra project â Zero Emissions șĂÉ«ÏÈÉúTV Renewing Alnwick â the original target for the design team was to get a BREEAM âexcellentâ rating. But the schemeâs completion date was uncomfortably close to the governmentâs own 2012 target to make its central office estate carbon neutral. âWe werenât going to get thanked very much for delivering a building which, when it was three or four years old, would have needed another million spending on it to make it carbon neutral,â says Ian Bailey of project manager Appleyards.

This prompted a rethink and as the design team began looking into the scheme in more depth, it realised there was a good chance that the building could be made zero, or near to zero, carbon.

The approach is a familiar one. First the design team aimed to bring energy demand down to a minimum through the buildingâs passive design. As a result, the two-storey building is split into a pair of narrow blocks that are positioned to make the best use of winter sun while minimising unwanted summer solar gains. Floor plans were sized so that the building could be naturally ventilated throughout much of the year, while in winter months there is a low energy displacement ventilation system with heat recovery.

Meeting the energy needs are three wind turbines, photovoltaics, solar hot water heating and a biomass boiler. Itâs a familiar technological roll call. However, it is the way the project has been delivered that stands out. âWhat we couldnât do with this building was hand it over to Defra and just walk away,â says Neil Reed of Appleyards. âWhat weâve given them is a building that enables them to be sustainable and zero carbon but it needs to be operated correctly.â

From the outset, right up until they moved in, occupants have been included in the project through a series of workshops. This influenced the design in a number of ways. For example, Defraâs staff said they wanted to be in control of their environment and did not want an anonymous electronic building management system opening and closing windows for them. The upshot of this is that the architect abandoned the original window design in favour of a more easily accessible version and a traffic light system tells them when to open and close them for the best environment.

The workshops have also meant the design team has managed to control expectations. âThey know they wonât be getting an air-conditioned office at a constant 21ĂC and weâve also told them at times theyâll have to put a jumper on if theyâre too cold â these things need to be made clear.â

The architectural concept also focused on providing the best possible low-energy solution, which meant the architect worked with the engineers right from the concept stage. âEverything we did was to get the best possible passive solution,â says architect Raymond Gill. âA lot of the normal architectural niceties were put to one side and the building developed its own aesthetic.â

Another feature was that contractor Kier Northern was on board when the project started. This meant that it could help with the development of the detailed design and importantly the design team could ensure that any value-engineering exercises would not result in missing the zero energy target.

Underpinning the entire design was BREâs environmental assessment methodology, which was used to set the agenda. At the outset they appointed a BREEAM assessor to see what credits it could achieve relatively easily, which it would need to work hard to get and which were out of reach. For example, the siteâs location meant it would not get any credit for being close to a busstop and of the 10 or 12 technologies looked at, some, such as ground-source heat pumps, did not stack up because of the buildingâs low heating loads, so credits were lost there.

This exercise identified 76 credits, enough to get an âexcellentâ rating, but it also showed that there was the potential to get this figure up to 82. However, says Reed, the potential to hit this target was dependent to some degree on the contractor which was set the challenge of getting the score above 76. For example, points were scored if it was part of the Considerate Constructor programme.

But knowing it was technically viable was one thing â the costs also had to stack up. As a public sector client, the project was analysed for its whole-life cost. Under Office of Government Commerce rules, the main aim was to provide value for money, not lowest capital cost, and it was agreed with the client that they should look at a 25-year life.

Each of the low-energy technologies was investigated. Although some, like the biomass boiler, had good payback periods â around two years â others such as the photovoltaics would not pay back in the time allowed. The decision was taken to look at the technologies collectively. âThe target was carbon neutrality and we needed the PVs to achieve this,â says Gill.

The total cost of the project came in at ÂŁ4.2m, or just over ÂŁ2,000 per m2. Although there are no official benchmark costs for sustainable buildings, a study by Davis Langdon puts it at the lower end of the scale for highly sustainable buildings and ÂŁ372/m2 below the average.

So how well did the Defra offices perform? Under BREEAM 2006 it achieved 80.72%. This is one of the highest-ever ratings and itâs also the first ever building to get an A+ energy performance certificate with net carbon emissions of â14kgCO2/m2 per year.

It is an impressive outcome, but the team behind project Zebra still feel they have the potential to wring even more out of the project. At the design stage, BRE picked up on the high score the building was likely to achieve and used it as a pilot to develop its BREEAM 2008 methodology.

So the question really is, how well would it fare under the updated criteria, and will it achieve the credits needed to secure the first âoutstandingâ ranking?

Under the latest version, the areas of assessment remain largely the same, but the weighting has changed, with mandatory targets introduced. As the bar is raised, project Zebraâs 80.72 credits are unlikely to translate into exactly the same score, leaving an âoutstandingâ ranking â a minimum of 85 credits â out of reach.

But where there is new potential to gain points is through âinnovationâ credits. According to Tim Bevan of BRE, this has been introduced to recognise aspects not already covered in BREEAM. There are two approaches. The first is exemplary performance, where a project goes above and beyond the typical requirements of BREEAM. Energy is a typical example. Fifteen credits are available, which would be equivalent to a high Aâ rated energy performance certificate. However, a zero-carbon building or one exporting net energy back to the grid has the potential to get extra credits beyond the standard 15.

Second, the project team can apply to have something recognised as innovative. This could be anything from a new technology, a way of procuring the building, or a process used by the contractor. Once it has been assessed as eligible it will then be reviewed by a panel of experts who will decide whether it is truly innovative and deserves to be recognised.

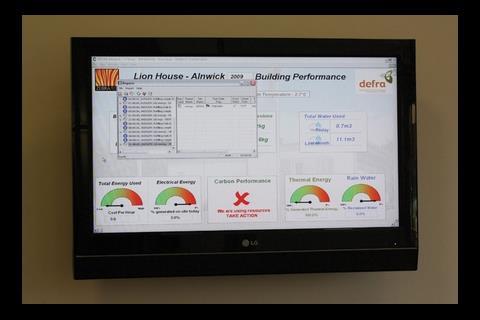

Innovations that Marc Fincham of Appleyards is hoping might be eligible include the structured workshops used to educate the occupants, the traffic light system for opening and closing the windows, the buildingâs energy monitoring display, which gives occupants live data on how much energy the building is consuming, and the habitat enhancement zones created in the landscaping.

By its nature the âoutstandingâ rating is not meant to be easy to obtain but the design team behind project Zebra is quietly confident that they will have enough to hit the 85 credits they require. âWeâve done a first run on the credits assessment and we think weâve got the right ingredients to reach it,â says Lee. The aim is to resubmit the project in the coming months. Watch this space.

The technologies that help make DEFRA zero carbon

Wind turbines

Three 15kW wind turbines provide the bulk of the electricity for the offices. Although these domestic-sized units are less efficient than a single large turbine on a 25m mast, they were seen as a more acceptable solution by planners.

The procurement and installation of the turbines was the most problematic element of the project. According to Neil Reed of Appleyards this is partly because it is still a relatively immature industry. Part of the problem was their positioning, which had to avoid wind shadows from the building. The original siting was later changed to enhance their performance, which required a new planning application to be submitted, the outcome of which was not known until the final months of the project. Reed says one of the lessons learned is that their procurement and position should be decided much earlier.

âIf we had looked at them sooner it would have given us longer to resolve the issues. We did start becoming anxious in August when we didnât have complete certainty that we would have planning for them even though we were only moving them 1m to the left.â

Predicted energy supply 60,000kWh/year

Expected CO2 savings 34,080kg/year

Biomass boiler

With six wood chip suppliers within five miles of the site, a biomass boiler was the logical choice for heating and hot water generation. The 40kW boiler can run on wood chips or pellets and will provide up to 90% of the peak heating requirements with a small gas-fired unit installed for peak times and as back-up.

Predicted energy supply 40kW

Expected CO2 savings 2,400kg/year

Embodied energy

A study carried out by Davis Langdon showed the building to have an overall embodied carbon of 1,466kg CO2/m2 of gross floor area (excluding fixtures and fittings). As would be expected, the bulk of this is contained in the foundations, floorslabs, stairs and building frame. The architects worked with the engineers to create a hybrid structure for the building. This essentially comprises of a steel frame, glulam columns and exposed concrete slabs for the ground, first and roof level. Taking into account the recycled content of the steel, the embodied carbon reduces to 1,289kg CO2/m2.

Water consumption

Mains water consumption is being minimised through a rainwater harvesting system and low-water-use fittings. The target is 1m3/person/year, which is a third of normal best practice targets.

Materials

All major building materials have an A rating for their environmental impact, according to BREâs Green Guide. This resulted in some of the original fittings, such as the composite windows, being substituted for timber versions.

Solar water heating

An array of evacuated tube collectors are located on the roof of the building and are predicted to delivery about 40% of the annual hot water demand.

Predicted energy supply 4,160kWh/year

Expected CO2 savings 807kg/year

Photovoltaics

About 110m2 of PVs are installed in four arrays. These are integrated into the brises-soleil shading the south facades of the ground and first floors of the two blocks.

Predicted energy supply 7,500kWh/year

Expected CO2 savings 4,260kg/year

Client design team

Client: Defra Estates Division

Project managers: AppleyardsCost consultant: Davis Langdon

Architect: Gibberd

șĂÉ«ÏÈÉúTV services and structural engineer: Faber Maunsell

CDM co-ordinator: CPS UK

Sustainability consultant: Element 4

Design-and-build team contractor: Kier Northern

Architect: Frank Shaw Associates

șĂÉ«ÏÈÉúTV services: Haden Young

Structural engineer: Faber Maunsell

BREEAM assessor: 3 Planets

Landscape architect: Anthony Walker & Partners

Ecological consultant: E3 Ecology

Original print headline - OKay, it looks modest, but itâs got some big ambitions

Downloads

Actual and projected energy use and carbon emissions

Other, Size 0 kb

Detox issue: January 2009

- 1

- 2

- 3

Currently reading

Currently readingBig ambitions: Defra's Alnwick HQ

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

3 Readers' comments