Damage to towns and local democracy ‘unacceptable’

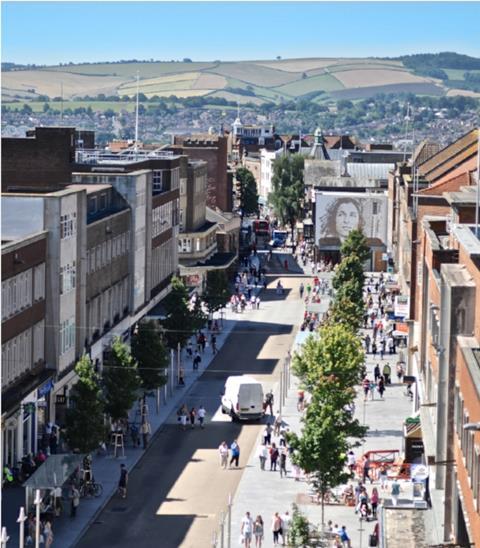

Architects have warned of the “disastrous unintended consequences” of a government proposal that would allow entire high streets and town centres to be converted into housing.

The “half-baked ideas” could do irreversible harm to the commercial hearts of towns and cities up and down the country, they said, and render local authorities powerless to intervene in shaping their districts.

Former RIBA president Ben Derbyshire said the loss of local democratic control was unacceptable at a philosophical level – and questioned ministers’ claim that the proposal would breathe new life into cities. Instead he predicted that footfall would plummet with devastating results.

In a consultation announced this month the government proposed the creation of a new permitted development (PD) right, effectively granting permission for the vast majority of commercial buildings in England to be converted to homes.

The proposed right, which could come in to force as soon as August and does not require primary legislation, would apply even in conservation areas.

It would allow any buildings in the newly created “Class E” use class to be converted into homes without planning consent.

Class E covers the vast majority of non-residential town centre uses, including offices, shops, restaurants, estate agents, gyms, GP surgeries and nurseries – and many more. Only a small number of distinct uses kept outside Class E because of their unique characteristics or community value – such as pubs and theatres – will be exempt from the new right.

The proposed right is much wider ranging than existing conversion rights, introduced in 2015, which have seen more than 72,000 homes created from former offices and light industrial units. Not only does this extend the right to many more building types – restaurants and cafes, clinics and creches for example – but the tight size limits imposed on many of the existing rights would be removed.

Until now, for example, while developers have technically had a permitted development right to turn shops and professional services premises into homes, this has only applied to properties smaller than 150sq m.

Now, however, properties of any size can be converted without planning permission – meaning the largest shops on the high street could be quickly converted into homes, with no right for the local authority to object.

In order to undertake the conversion, developers will have to meet space standards and ensure the provision of “adequate” natural light, as well as meet a handful of other tick-box “prior approval” criteria – a response to the growing criticisms of the poor quality and small size of many existing homes created under PD rules.

However, these prior approval criteria will not allow local authorities to object to the conversion on the basis that they want to retain commercial uses in a particular location, or in order to support the delivery of local plan policies around town centres.

The proposal also goes further than previous rights in that it will apply in conservation areas – albeit with an additional prior approval criterion added to consider the impact of conversion on the conservation area.

Only a short list of areas – including National Parks and Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty – will be exempt from the new right. However, local authorities will have the ability to apply for so-called “article 4” directions exempting specific areas from the measures, if they can mount a persuasive case as to why that is necessary. A number of London boroughs, for example, managed to secure similar exemptions from the 2015 office-to-resi rights. And they were enthusiastically deployed by prime minister Boris Johnson when he was mayor of London to protect the capital’s commercial heartland.

Local authorities will not be able to object on the basis that they want to retain commercial uses in a particular location, or in order to support local plan policies around town centres

The new proposal is so far-reaching that leading planning barrister Zack Simons, of Landmark Chambers, said it was by far “the most radical planning reform of the year”, despite the publication of the Planning for the Future white paper in the summer, and the bringing in of a raft of other controversial permitted development rights (such as the right to demolish and rebuild commercial property).

Holly Lewis, co-founding partner at We Made That which has extensive experience of working with local authorities on urban realm strategies, told ∫√…´œ»…˙TV Design: ‚ÄúWhen have you ever walked through a residential area and thought, ‚ÄòWow! This place is buzzing!‚Äô? It‚Äôs common sense that uncontrolled switching of high street units into housing threatens the vitality of our town centres.

“Opening up high streets to property speculation as a misguided attempt to answer current challenges will only exacerbate the ingrained inequalities that have been so starkly exposed by the pandemic.”

Julia Park, Levitt Bernstein‚Äôs head of housing research who was named ∫√…´œ»…˙TV Design‚Äôs Architect Leader of the Year in October for her campaigning work exposing the poor quality of PD housing, questioned the government‚Äôs haste.

In a column published today she writes: “It is hard to imagine that the re-purposing of high streets and town centres will ever be reversed so these decisions cannot be taken lightly.

“Given the long-term impact that so many of these half-baked ideas will have, local authorities surely deserve time to plan for an orchestrated shrinkage of town centres and high streets, incentivised by favourable business rates for non-residential uses – and we deserve a planning process that upholds local democracy.”

Ben Derbyshire, chairman of housing specialist HTA Design, warned of the chaotic free-for-all that would ensue.

“As everyone knows, including Robert Jenrick, a successful high street has to be curated: ask any of the Great Estates in London,” he said. “Marylebone High Street prospers because someone really cares about who’s there and the shopping experience.”

He warned: “The amount of activity of high streets would plummet and that has to be really carefully managed – and that’s before we get to the quality of the accommodation itself.”

PD conversions would bring in no section 106 money and councils would also lose business rates, while at the same time facing a potentially higher social services load as a consequence of people living in substandard accommodation. He also questioned how the new homes would be serviced with no space for wheelie bins among other issues.

Derbyshire urged the profession to “keep up the criticism until the disastrous unintended consequences have been averted”, pointing out that some U-turns on PD rights have already been won by campaigners, such as the requirement for space standards to apply and for habitable rooms to have a window.

No comments yet