Damage to UK roads due to flooding has put a spotlight on the condition of our highways, at a time when the maintenance backlog is already estimated to be at least £10bn. Barbra Carlisle and Brian Fitzpatrick of EC Harris examine the key issues

01 / Introduction

The UK’s highways network is a complex and crucial infrastructure asset that influences our economic performance by enabling the movement of people and goods, contributing to workforce productivity and enhancing connections. The authorities that manage our roads must deliver high levels of availability, with cost, safety and sustainability constantly at the forefront of any decision-making, and face continual efficiency-saving challenges that are unlikely to diminish in the near future.

We see the demands on our ageing highways assets increase as car ownership and mobility increase, distance travelled increases and loads increase. The challenge is to create additional capacity, particularly on our Strategic Road Network (SRN), and to get the most out of all our road assets with limited funding. A number of factors influence decisions around asset improvement or repair, including:

- How safe the asset is to use in its current condition

- The criticality of the asset

- The level of investment required

- The level and quality of available data on asset condition

- The ability to analyse and interpret asset condition data

- Asset management strategies and availability of performance and forecasting tools

- Highway authority priorities

- External influencers, such as government funding availability or government direction

- The availability of technology to assist in asset management and asset maintenance.

Prevention is better than cure, so managing when and how renewals, repairs and enhancements are carried out impacts upon asset life and lifecycle costs. Knowing the condition of an asset is an essential part of a prevention approach, but unfortunately, due to the historical evolution of our local road network, the composition of local roads is not always known. This makes asset management a real challenge.

02 / The highways network

Our highways network covers roads, bridges and culverts, tunnels, and telecommunications. It can also include lighting and footways. The network is complex and dynamic, in that asset conditions vary and components constantly change through renewal, enhancement and realignment. The condition and quality of the network affects the risk of accident, damage and injury to users. In Great Britain there are 245, 400 miles of road assets, the majority (87%) owned by local authorities. The remaining 13% are trunk roads and motorways - the SRN - which account for 65% of all road traffic.

Roads are recognised as an enabler of economic performance, facilitating the movement of goods and people - over 80% of domestic freight is moved via the UK road network. One in five of all our local roads are in poor condition, and almost three-quarters of UK businesses express concern about local road deterioration. The World Economic Forum’s Global Competitive Report ranks the UK 28th in terms of quality of roads in 2013/14, a drop of four places since last year. The UK is below Spain and only marginally above Namibia.

One issue influencing investment is that roads can still have restricted use even where there is need for maintenance - for example, if there are potholes or cracks in the road. When budgets are squeezed, local authorities focus funding on more immediate non-highway needs.

How local authorities prioritise within highway spending is also an issue. For example, potholes are a vote influencer, potentially causing damage to road users, so authorities have tended to spend on repairing them in a reactive manner. This approach reduces funding available for capital and planned maintenance. For example, in 2011/12, 25% of local authorities’ road structure budget was spent on reactive maintenance, against an ideal target of 15 %. The Asphalt Industry Alliance states that it is 20 times more expensive to patch and repair than to undertake planned maintenance.

With traffic volumes on the SRN alone forecast to grow by 45% from 2003 to 2035 and the continued increase in light goods vehicles on our roads (20% since 2003), the highways network needs to adapt to accommodate change. Risk-based asset management strategies are essential to planning and ensuring smooth traffic flows on good quality roads that are future-proofed.

03 / Stakeholders

Ownership and management of UK highways is shared between government agencies, cities and other local highways authorities. The secretary of state is responsible for trunk roads and motorways in England - the SRN. Trunk roads and motorways are the major arteries that join conurbations. Other roads are managed by local authorities.

The Department for Transport (DfT) is the sponsoring department in England, working with the Highways Agency (HA), which manages the network on the government’s behalf. Similarly Transport Scotland manages the SRN on behalf of the Scottish executive. Northern Ireland is different as the Northern Ireland Road Service (NIRS) manages all roads, while the Welsh government is responsible for all trunk roads. Funding is from central government.

There are also a number of design build finance operate (DBFO) trunk roads, primarily in England, where private finance is used to build and manage assets on 25 or 30-year contracts. Examples include the Severn Bridge and the M25 in England, the A55 to Anglesey in Wales and parts of the M74 in Scotland.

Most of our roads are non-trunk roads, owned and managed by 250 local authorities. Some local authorities also have responsibility for sections of their own motorway links. Local highway assets tend to be older than the SRN, having developed over time as urbanisation and population increased. Due to their age, location and shifting trends in road construction throughout history, the actual composition of the foundation of the road is not always apparent. This makes proactive planning more difficult.

While there are differences in the standards and management approach across the UK, there are a number of common attributes that affect how the SRN is managed:

- SRN assets are newer than local roads and are engineered roads, with future-proofing built into the initial design, typically segregated from other roads

- Road asset construction composition is known, enabling preventative approaches to be developed

- Road assets tend to be straighter, with fewer curves, reducing wear and tear and enabling deployment of high-speed deflector-graph machines to aid asset condition assessments.

In addition, the SRN managers do not have the same level of mandatory engagement that local authorities have with statutory undertakers. Non trunk and motorway networks facilitate the location of statutory undertakers’ assets. Statutory undertakers - for example, utility companies - run their services under and along roads and have the right to repair. This includes digging up roads to enable access to repair, maintain and renew their subsurface assets, potentially disrupting traffic and affecting the condition of the asset. Where access can complement asset management plans disruption can be kept to a minimum.

Statutory undertakers’ relationships with SRN managers are different, as services tend to run longitudinally alongside the SRN, and can be designed into construction and maintenance activities. Relationships and asset management strategies are therefore significantly different across the highways network, with planning maintenance less complicated in that respect.

Other stakeholders include:

- Developers who may require road modifications or enhancements, such as junction modifications, to accommodate their developments

- The Health and Safety Executive and other road safety groups

- Road-focused organisations such as the RAC, the AA and the Road Haulage Association

- Representative bodies such as the CBI, environmental groups and road user groups.

04 / The changing environment

The way that highways assets are managed is changing. In England, the HA’s move towards commissioning asset contract support (ASC) contracts to manage the maintenance of the SRN, replacing managing agent contracts (MAC), places greater emphasis on outcome measures. Performance measurements are set around five key objectives:

- Providing a service customers can trust

- Setting standards for delivery

- Delivering sustainable solutions

- Providing the safest roads in the world

- Providing dynamic and resilient network assets.

Similarly new regional technology maintenance contracts (RTMC), delivered under the supervision of the ASCs on lump-sum deals, have a more outcome-focused performance measurement framework. RTMCs focus on optimising traffic flow, incident management and information provision through targeted technology maintenance.

SRN funding includes evolving and increasing the number of Smart Motorways (an evolution of Managed Motorways). Smart Motorways use technology to manage behaviour.

- Controlled motorways: variable speeds using technology to manage queues

- Hard shoulder running: temporary use of the hard shoulder to support incident management strategies

- All lane motorways: variable speeds, and no hard shoulder.

Smart motorways are used to assist traffic flow and ease congestion. They also enable the HA to use resources well as they minimise the need for planning permission (the hard shoulder being already owned by the HA), as well as helping to reduce pollution through the introduction of speed limits. Several Smart Motorway schemes are being delivered under the accelerated highways programme - for example, the M25 junctions 23 to 27.

The efficiency with which assets are used is as important as the underlying investment. Maximising capacity at minimum cost is a central part of the DfT’s long-term plans. Its announcement of a £24bn road investment programme to 2020 is framed around the need for the sector to seek efficiencies in the way roads are managed.

In an effort to improve efficiency and transparency, the DfT’s Action for Roads: A Network for the 21st Century proposed a number of changes for England, including transformation of the HA into a government-owned company (GoCo). This would have greater autonomy than the current HA, which it is hoped will lead to more efficient management of the SRN. This would be achieved through:

- longer term funding commitments

- creation of an asset performance based approach, with accompanying transparency and accountability

- separation from politically led decision-making.

At a local level in England, local authorities are being encouraged to work together, including through local enterprise partnerships (LEPs), to determine priorities for spending. Highways maintenance block funding is also under review. The review includes linking funding to evidence of good-practice asset management principles. Cost benchmarking, LEAN and Six Sigma methods are all tools that are likely to be increasingly adopted by highway authorities in their efforts to develop risk-based asset management strategies that satisfy new funding requirements.

In London, the Road Task Force brings together stakeholders including Transport for London (TfL),which is responsible for the city’s SRN (the “red routes”), and local authorities, which manage the other roads. It aims to provide a strategic framework to enhance the capital’s urban realm by providing advice around operational, policy and investment decisions. With road works and traffic delays estimated to cost London’s economy £1bn a year, and an anticipated £30bn of investment needed over the next 20 years, asset management planning such as the London Highways Alliance Contract, is essential for the capital.

The Highways Maintenance Efficiency Group (HMEP) supports effective asset management across the highways network by providing guidance and good practice examples from within the sector. There are also great opportunities to learn from other sectors, including around risk management, transferring risk to the supply chain, supply chain management and best technology. However, standardisation and promotion of a single source of best practice are difficult in the industry because of, among other things, the diverse objectives of highway authorities and a varied approach to risk.

Capital and revenue funding for highways assets is generally obtained from central government (DfT and the communities department). In specific instances some operators receive income from users - for example, the M6 toll motorway.

Spend

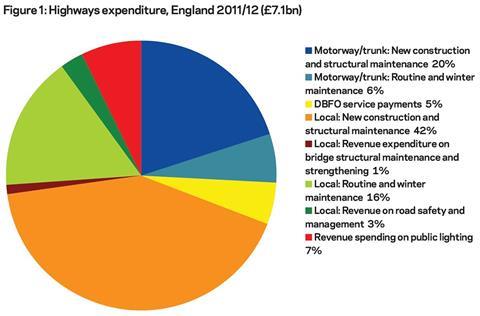

In 2011/12, £7.1bn was spent on highways in England (see fig 1). Just under half was on the construction, improvement and structural maintenance of local roads. Structural maintenance covers significant work that is required to maintain the highways. It can include reconstruction of the carriageway as well as repairs to kerbs and footways.

Structural maintenance also includes repairing roads due to potholes. In 2012, over 2 million potholes were filled in, costing on average £52 per pothole in England and £47 in Wales. Trying to identify maintenance backlogs in a consistent manner is a challenge and approaches are set out in authorities’ transport assessment management plans (TAMPS). In Wales and Scotland partnership working between agencies has led to the commissioning of backlog maintenance assessments and asset condition surveys.

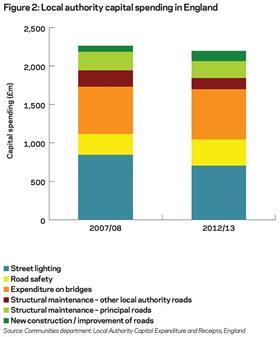

When we look just at local authority “new construction and improvement” spending (see fig 2), we see that the capital expenditure budget has reduced over time, and that more is now spent on structural maintenance and road bridge expenditure than on new and improved roads.

The way that English local road schemes are funded will change from 2015. The government is currently consulting on how to create a more outcome-based funding environment to encourage efficiency and innovation in highways management. Top slicing part of the overall national funding allocation, creating a competitive environment whereby local authorities bid for major local maintenance funding, is one suggestion. Another is linking funding allocation to local asset management strategies.

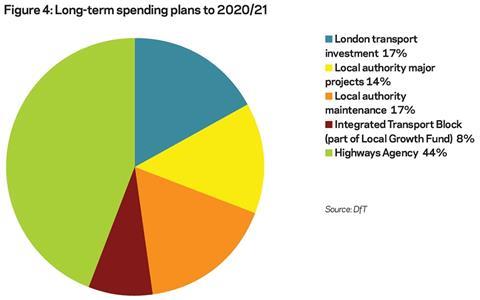

Spending of £24bn was announced in the latest comprehensive spending review, with committed expenditure to 2015/16. A breakdown of long-term plans shows that HA funding for trunk roads and motorways accounts for 44% of spending.

Investment will:

- add extra lanes to the busiest motorways, largely through smart motorway schemes

- tackle the most congested parts of the network - for example, the M4 from London to Reading

- enable solutions, starting with feasibility studies, to tackle longstanding hotspots such as the A27 on the South coast

- upgrade the HA’s non-motorway network including pinch-point schemes

- resurface 80% of the SRN

- repair highway assets through well-designed capital maintenance programmes.

06 / Procurement and supply chain

Asset management plans, road investment strategies and route-based strategies are all designed to improve performance by setting priorities and performance specifications for capital and maintenance spending. Route-based strategies, which are designed in consultation with stakeholders, including LEPs, are part of a new approach to SRN investment planning in England. All are based on maximising the capacity of existing highways networks and looking at how to minimise expenditure for maximum impact. The drive to combine financial efficiency with high levels of safety and sustainability sees contractors taking on contracts that have a number of outcomes including regeneration, reducing road fatalities and increasing inward investment.

Highways authorities work with the supply chain through a series of supplier frameworks. Category management frameworks for specific highways services are common, as are specific frameworks for large, medium and small contracts. Category management frameworks encourage efficiencies in the procurement of specific materials and products, such as barriers and signs.

Working in collaboration with other local authorities is also increasingly common. For example, Midlands Highways Alliance covers 17 local authorities and has a major schemes programme for projects between £12m and £50m. Savings are achieved through aligning asset management plans, smarter procurement approaches and pooling specialist technical and management skills.

Other highways authorities have gone down the PFI route. For example, Portsmouth, Birmingham and Sheffield have all committed to PFI to renew and maintain their highways. PFI deals bring ring-fenced funding to highways networks, enabling an extensive programme of capital expenditure to renew assets, followed by a long-term programme of maintenance to deliver defined asset performance levels. The PFI deal between a client authority and suppliers incentivises a whole-life cost approach to highways asset management. Capital spending decisions are linked to operational performance and maintenance intervention programmes recognise capital spending implications.

The HA operates some frameworks nationally, others regionally and some as standalone entities . Some Smart Motorway contracts are via a national framework, awarded on a single tender basis. Asset management and maintenance contracts with Tier 1 and 2 contractors are through regional frameworks. For example MAC/ASC contracts and traffic management contracts are awarded region by region. HA frameworks embrace:

- an alliancing approach

- risk sharing and incentivisation linked to performance

- early contractor involvement

- target cost savings.

The supply chain is mature and we increasingly see alliances and consolidation. Suppliers look to provide one-stop shops with the ability to design, plan, build and maintain highways assets across a region or a city, drawing on specialist contractors through alliances and joint ventures. Larger contractors also offer a managing role, co-ordinating maintenance schedules, bringing together specialist contractors and alleviating day-to-day management worries for the highways authorities. Value comes from:

- use of contractor technology, such as scheduling software to help match physical and financial resources

- having a long-term programme that allows contractors to price with certainty

- the contractor’s flexible workforce, including 24-hour response services

- performance payments, with incentives to exceed performance, and penalties for not meeting performance

- lump sum contracts.

Quality within the supply chain is promoted through initiatives such as the National Highway Sector Scheme, a quality management system used by the HA. The Highways Maintenance Efficiency Programme and Highways Efficiency Liaison Group also provide examples of how to improve supply chain quality,including maintenance models that incentivise efficiency, and models of risk transfer. Standard contracts for procurement based on NEC3 are becoming increasingly common for local roads contracts. Standardising local procurement contracts reduces the financial burden on the supply chain at tender stage, and makes it easier to identify risk and price the work more accurately.

Proposals for the GoCo in England include using road investment strategies to determine funding levels over set periods. These periods need to be designed to help supply chain planning and avoid a system that sees peaks and troughs of spending.

05 / Costs

The types of scheme that are currently prevalent within the market could be classified somewhere between capital builds and larger maintenance projects. The key distinction between them is that the latter is more likely to be affected commercially by method of construction, programme, working patterns and associated enabling / access works whereas traditionally highways works have generally been considered quantity driven.

Major schemes

Cost per carriageway area (excluding structures) should lie within a range of £113-184/m2. This cost range reflects captured benchmarked projects which included the earthworks elements of construction. It is found that the earthworks elements are a key variable factor when providing benchmark data as each scheme is unique in nature. With this in mind, excluding the earthworks elements, a cost per carriageway area range between £81-119/m2 is considered appropriate.

Maintenance and lifecycle costs

Generally, highways lifecycle replacement tends to involve removal of running surface and replacement coupled with an element of ad-hoc structural repairs. The basis of the cost of the operation is the laying of surface course, which generally costs about £8-12/m2. However, consideration needs to be given to milling operations, traffic management and time of operation, which have significant commercial implications.

PPP/PFI factor

One of the areas of consideration is not only the cost of the lifecycle replacement of the highway asset, but the frequency and timing of the interventions. Being able to accurately model the highway degradation and plan specific interventions to balance against the contractual requirements and long term profitability of a concession can be the difference between winning and losing major schemes. However, it is interesting that this element of a scheme may not be directly “cost” related, as there is the emergence of this third tier supply contract market which changes the dynamic of developing a budget proposal.

The opportunities around selling or re-tendering concessions for long-term maintenance arrangements revolve around the realisation of risk and opportunities that are inherent in long-term infrastructure maintenance contract budgets. In short - we will know a lot more in 15 years. As the concession progresses, scenarios are understood, therefore better predictions can be made with lower levels of contingencies needed. This “efficiency” is now being considered up-front to make bids more competitive by using progressive analytics and scenario testing.

Thanks to our colleagues Paul Gilkes and Dave Culbert for their insight

No comments yet