The abandonment of Zaha Hadid’s Architecture Foundation HQ in London was a disappointment for design connoisseurs, but what does it tell us about the ambition of the British construction industry?

Zaha Hadid has been labelled a diva so often she has made a fashion statement of it. At the opening of the Cincinatti Arts Centre, her first major completed building, the project team wore T-shirts bearing the slogan: “Would they call me a diva if I were a guy?”

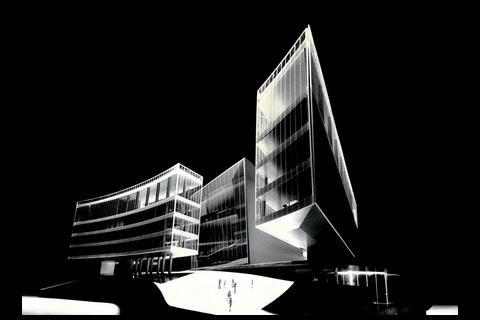

Diva or not, nobody can deny that her buildings look incredible. Soaring masterpieces of undulating glass and freeform concrete that seem to defy the laws of physics. A new image from Hadid will nearly always make it onto ��ɫ����TV’s news pages, usually the front one.

However, it’s not just her designs that make the front page. With depressing familiarity, the end products are delayed, over budget or scrapped. Take the Olympic aquatics centre, for example. Announced with fanfare as the architectural jewel in the crown of the 2012 London Games, it has been scaled back, redesigned and has scared off all but one contractor – and before a brick has even been laid it is three times over budget.

At least that will get built. Even after the appointment of a “managing architect” and two contractors, Zaha’s £5m Architecture Foundation HQ was axed last week.

Since Hadid set up her practice in 1980, only a scattering of buildings have been completed – 11 in central Europe, one in America, and one in Scotland. Many more are in development, but the Iraq-born architect is unlikely to have anything completed in England before 2012.

Why are Zaha’s projects so problematic? Are their difficulties symptomatic of a growing reluctance in the industry to take on signature architecture? And now that the construction market appears to have peaked, will it be easier or more difficult to get challenging projects like hers built?

Nobody at Zaha Hadid Architects wished to contribute to this article, but others who are working closely with the practice say her reputation as a diva is undeserved. WSP is the consultant engineer on three Zaha Hadid commissions in Kazakhstan, as well as projects in Libya and the Middle East, all of which are at an early stage. Bill Price, director of buildings at WSP, said: “We’ve found them to be pragmatic and sensible about costs and practicalities. But we know of their reputation as challenging people, so it could be that we’re in a honeymoon period!

“Up to this point our experience has been a traditional, considered process of dialogue,” he says. “The back of the envelope could still appear, but I really do doubt it.”

This experience is echoed by Ken McAlpine, HBG’s Scotland director, whose firm is set to build Hadid’s £74m Glasgow Transport Museum. Although HBG ended up being the only contractor willing to take it on, McAlpine is sanguine about the work. “This is the first Zaha Hadid building we’ve taken on,” he says, “but I don’t think it’ll be the last. There’s nothing to be frightened of if it’s priced on the right basis.”

None of the big-name architects we work with particularly want to make life easy for us, but why should they?

Bill Price, WSP

McAlpine says the museum has a complex design but having worked on a number of projects with the council and engineer Buro Happold, HBG is confident the project will progress smoothly. “We’ve built complex projects before. Why should this one be any different?” he says.

The success of a complex project rests on how easily the project team is able to solve whatever problems may arise. This job is design and build, so the team has a lot of flexibility. Just as well, given the budget has already swelled by £14m since the project was announced.

Indeed. But somewhere like London, where the market is still overheated, contractors might find delivering a complex design a risk too far. Ken Shuttleworth, whose practice Make Architects has several schemes under way in the capital, says that may be a problem for someone like Hadid.

“There’s been so much work on contractors don’t need to go for it,” he says. “It’s much easier to go for simpler stuff, especially as there’s been a move back to construction management as the credit crunch goes through. There has been a process where radical things are getting scaled back.”

Will Alsop, whose designs are almost as complex as Hadid’s, says there is still an appetite among contractors for difficult jobs, but in the financial climate it is a matter of scale. “I was talking to a contractor this morning, and he said they like nothing better than a medium-sized challenging project, up to about £50m or so,” he says.

The question is, are they willing to do it on a grander scale? Although Hadid’s designs are spectacular, they are difficult to build. “In terms of geography and aesthetic difficulty, the Hadid projects we’re working on are among the most complex that I’ve ever done,” says Price, which is significant given he has worked with Gehry, Nouvel and Calatrava.

“None of these big-name architects we work with particularly want to make life easy for us, but why should they? These guys are knowledgeable about what engineers can do, and ultimately it is a positive thing, because you get a better building.”

Price’s use of the word “guys” may irritate the Cincinnati Arts Centre team, but semantics aside it’s a slap in the face to cynics who say that Zaha’s contribution to a building is a squiggle on a notepad handed to the engineer. In the end, the industry needs architects like her to build impressive buildings. To that end it is to be hoped that contractors are not scared off. Alsop says: “Attractive buildings bring people joy, and happiness saves the country a huge amount of money. And of course they help with tourism, and so on. So, if contractors are fighting shy of building great buildings, then they’re doing the country a huge disservice.”

1 Readers' comment