Construction is full of people whoŌĆÖve lived the Olympic dream. As the Beijing Games kick off, eight of them tell Emily Wright about their years of training for moments of glory. Photography Michael Clement

Andy Beadsworth

Olympics Fourth in Atlanta 1996 and 12th in Sydney 2000

Sport Sailing (three-man keel)

Current job Formerly a civil engineer with Tilbury Douglas, now a full-time sailor and coach, currently working on Sir Robert McAlpineŌĆÖs boat, Panthera

The year before I was selected for the 1996 Atlanta Games I remember thinking to myself ŌĆ£this is something I could be doing for the rest of my life and never get the chance to go to the OlympicsŌĆØ. So when I was chosen, I was euphoric.

In sailing, they select teams a year in advance so people can get over their excitement and refocus, because when you arrive itŌĆÖs incredible and you can easily get distracted.

Competing is a culmination of years of work; it becomes a lifestyle. The hardest thing to cope with is coming out the other side, especially if you havenŌĆÖt achieved what you wanted to. Everything just stops and it can feel very empty. You get over it by looking for the next challenge.

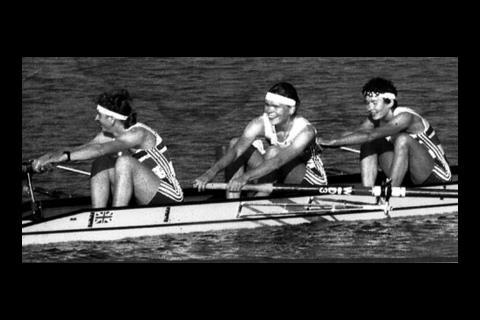

Kate Grose

Olympics Sixth in Seoul 1988 and seventh in Barcelona 1992

Sport Rowing (coxed fours in 1988 and eights in 1992)

Current job Director of Tiger Stripe Architects and Tiger Hill

Reaching the final in Seoul was amazing: we were an inexperienced team and it was unexpected. One of the journalists even filed his report from halfway down the course saying ŌĆ£failed to qualify, as expectedŌĆØ.

Our coach had managed to convince us we could do it, telling us our main weapon was surprise as none of the other teams saw us as a threat.

At the end of the race (pictured) we were knackered, but with none of the head-hanging you get if youŌĆÖve failed so we didnŌĆÖt notice the weariness. We were elated as we were the first British womenŌĆÖs crew to race in an Olympic final.

None of this comes easy, though. We trained twice a day, six days a week leading up to the Games. I was setting up my own firm at the time but luckily I was working with my brother, who was very supportive. We handled what work we could but admittedly a few things fell between the cracks because of my training.

Rowing was a huge part of my life, but it was not my whole life. I am sure that keeping this balance was better; it meant that, after the Games, I could get on with my career in architecture.

James Beevers (on the right of his father, Martin)

Olympics Sydney 2000

Sport 28th in fencing (foil discipline)

Current job Business development executive, Construction Industry Council

Nothing quite prepares you for the overwhelming scale of the Olympics and it is all too easy to crumble under the pressure. You just have to focus. I qualified for the Sydney Olympics in 2000 during my final year at university.

I actually flew off to the Games the day after my graduation ŌĆō quite a week.

What struck me most about the Olympic village was how big it was. It needed an internal bus system to transport athletes around it.

On my return from Sydney I decided to kickstart a full-time career but there were not enough hours in the day to work and train. I would try and get to the gym in my lunch hour a few times a week and spar at a London club in the evenings, but ultimately my training suffered badly. Luckily at the Construction Industry Council I have the flexibility to train and develop my career as well.

These days, a typical week consists of three or four squad sessions, one or two strength and conditioning and sports psychology sessions, and personal training. Life is very busy but I wouldnŌĆÖt have it any other way. The thought of my young son watching me compete at the London Olympics is a huge incentive and one that always gives me a little extra spark at the end of a long day.

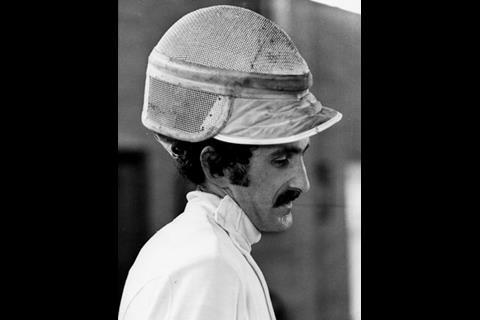

Martin Beevers

Olympics Montreal 1976

Sport Fencing (├®p├®e discipline)

Current job Senior structural engineer, Atkins

I remember how it felt competing in 1976. There was a supercharged atmosphere and we were on a natural high all the time. There was great camaraderie among the British team.

Bizarrely, I was not nervous at any time ŌĆō perhaps I should have been ŌĆō as competing at an Olympic level was something I had dreamed of since I had started fencing.

IŌĆÖm a civil engineer and after the Games I specialised in marine works. By October 1977 I was working on the construction of the port in Abu Dhabi. This was the start of a seven-year period as an expatriate and ultimately spelled the end of my fencing career.

Giving up the sport was very hard. But at least it continues to run through the family. I met my wife Lorna, also an international competitor, through fencing. Now my son James is the third generation of fencing champions in the family as LornaŌĆÖs father was army and combined services fencing champion many times and went on to be the pentathlon fencing coach.

Mark Whitby

Olympics Fourth in Mexico 1968

Sport Canoeing

Current job Chairman, Ramboll Whitbybird

Mexico 1968 was an Olympics of two halves: huge achievements alongside unbelievable repression.

Canoeing is an endurance sport and as Mexico City lies above 6,000ft we arrived in September, six weeks before the Games, to acclimatise. The next day the Olympic village was surrounded by ŌĆ£a military paradeŌĆØ and we were put under a curfew.

Just as the Games were about to open, the student unrest culminated with the massacre of more than 200 people and the arrest of many more at a rally.

As our event was in the second week we took advantage of our Olympic Village passes and I witnessed Bob BeamonŌĆÖs phenomenal long jump, a record that still stands.

We managed a disappointing fourth in the 1,000m semi-finals, but the anticipation of the finals did make my parents finally buy a TV.

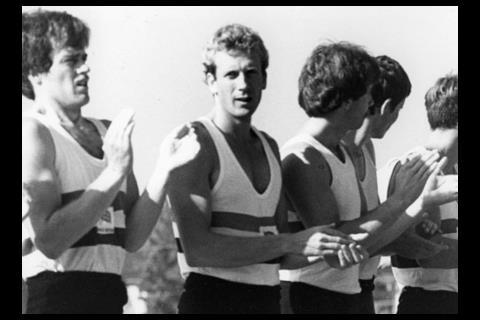

Malcolm McGowan

Olympics Silver in Moscow 1980. Also competed in Los Angeles 1984

Sport Rowing (eights)

Current job Managing partner, Sheppard Robson

Rowing training is tough and competitive. We trained twice a day, every day, all year. Our crew for the Moscow Olympics was formed late, but was a great combination and quickly showed potential. In the final we were just beaten by the East Germans.

After the Los Angeles Olympics I stopped rowing. After seven years in the national squad, I felt I didnŌĆÖt need to prove anything any more, either to myself or anyone else, and I was just not hungry enough.

I was lucky in that throughout my entire competitive rowing career I was an architect student ŌĆō itŌĆÖs very hard to train and hold down a full-time job.

Managing a company requires focus and teamwork and I hope some lessons from my rowing experience have helped me in my job.

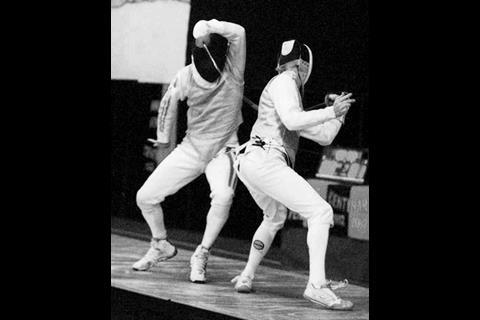

Graham Watts

Olympics Barcelona 1992, Athens 2004, Beijing 2008

Sport Fencing (sabre discipline)

Current job chief executive, Construction Industry Council

My Olympic experience started in 1992 as the captain of the sabre team. Our qualification was a miracle in itself: ranked 25th in the world, the team managed to sneak into the top 12 in the qualifying event.

I remember we went into the Olympic Village before the opening ceremony and spent three weeks there before our team competed on the last day ŌĆō nowadays we aim to get our athletes in just a couple of days before they compete.

Looking back, we were probably the last of a dying breed of good old amateur Brits trying to compete against state-sponsored professional athletes. IŌĆÖm proud of the fact that now the fencers representing Team GB in Beijing can match their opponents for skill and fitness and are every bit as professional.

Chris Houchin

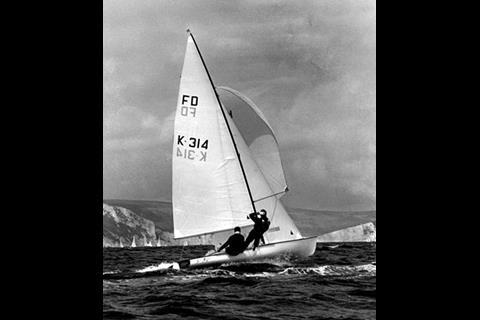

Olympics Selected for Moscow 1980

Sport Sailing (flying Dutchman class)

Current job Business development director, Bovis Lend Lease

I was selected to compete for Great Britain in the 1980 Moscow Olympics, but the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan led to a partial boycott of the Games. The Royal Yachting Association banned us from competing.

Sport and politics should not be mixed. I do think things have moved on since then so maybe we did our bit for future generations of sportsmen and women back in 1980. Having said that, I will be angry about the boycott for the rest of my life and seeing Malcolm McGowanŌĆÖs silver brought it all back ŌĆō I so nearly could have had one!

Support the team

The cost of sending 313 athletes to Beijing (plus 236 support staff) is not funded by the government in any way. The British Olympic Association depends entirely on voluntary contributions to meet the ┬Ż5m cost.

Recognising that the construction industry will benefit from the London Olympic projects, Graham Watts of the Construction Industry Council (alongside Terry Hill of Arup) has joined the BOA council to raise funds to support the British team at the Games.

To support Team GB, please contact Graham at gwatts@cic.org.uk

Postscript

Original print headline 'Nothing quite prepares you for the overwhelming scale of the olympics and it is all too easy to crumble under the pressure. You just have to focusŌĆÖ

No comments yet