It seems that Birmingham is on the cusp of a building boom. Dan Stewart took a stroll to find out

Whoever said the icon was dead? In the centre of Birmingham, Mecanoo’s design for the £193m Central Library has been unveiled and it is a bold architectural statement. This glowing stack of boxes, wrapped in a filigree iron cladding, demands the attention as the latest in a line of regenerative hubs in the Midlands city. Make Architects’ Cube development is in mid-construction, Foreign Office Architects’ revamp of Birmingham New Street station is soon to break ground, and now the self-styled “largest lending library in Europe” is set to complete the trio of design-led buildings going forward in Birmingham. And with £6bn of “recession proof” investment promised by the city council, could it be that while the rest of the UK’s development programme slows to a halt, Birmingham is about to become the dynamic centre of the UK’s building industry?

It would not be unfair to say that Mecanoo’s success in the 2008 competition was a shock. Pitted against such well-known UK firms as Foster + Partners, Wilkinson Eyre and Foreign Office Architects, the little-known Dutch firm was considered an outside bet. But its surprise appointment was merely the latest twist in the city’s seven-year struggle to build a new library. Richard Rogers was appointed in 2002 to design a building in the Eastside area of the city, but budgetary issues and council disagreements led to his design being scrapped. A second competition in 2007 for a site in the central Centenary Square yielded entries from David Adjaye, Glenn Howells and Ken Shuttleworth, but that too led to nothing. Only last year did the council finally find an architect for the library, which will be built on the Centenary Square site between the Birmingham Rep and Baskerville House.

Mecanoo’s appointment may have been a surprise – prior to the competition interview, Francine Houben, its director, had spent just three days in Birmingham – but the adventurous nature of its designs was not, given the practice’s history of designing buildings such as the Delft library in the Netherlands. Houben shies away from the i-word. “Please don’t call it an icon,” she says. “This is nothing to do with my ego. It’s all about Birmingham.” If New Street is Birmingham’s gateway, and Brindleyplace its office, then the Central Library is its living room.

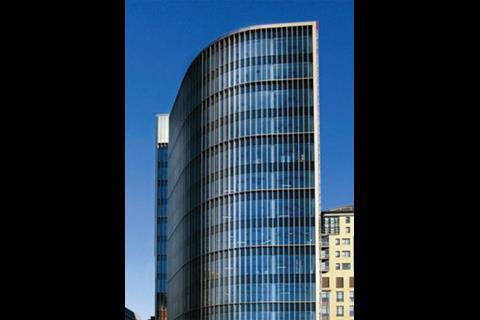

Centenary Square is broadly the central point in a loose, pedestrianised path ‚Äì a ‚Äúred ribbon‚Äù is how Houben describes it ‚Äì from Birmingham New Street to Brindleyplace, the canal-side commercial quarter on the eastern edge of the city centre. At the library‚Äôs launch, Clive Dutton, the city‚Äôs head of regeneration and planning, offered to take ∫√…´œ»…˙TV on a quick tour of that ribbon. First stop is Brindleyplace. The opening last month of Eleven Brindleyplace, Glenn Howells‚Äô commercial scheme, marks the final piece in the ¬£450m puzzle that, after a 15-year development period, has changed the face of Birmingham. ‚ÄúIt‚Äôs the end of an era,‚Äù says Dutton. ‚ÄúBut the completion of Brindleyplace means that our attention can move to the Centenary Square.‚Äù

Although its quaintly landscaped plazas are pleasant enough in a corporate sort of way, Brindleyplace is not studded with architectural gems. The only notable features are a Costa coffee booth designed by CZWG and an aquarium designed by Foster + Partners ‚Äì though this is notable for all the wrong reasons. (‚ÄúNot one of his best, is it?‚Äù says Dutton, as we gaze at its grey panels and garish lettering.) What Brindleyplace does do is provide decent commercial space, thereby bringing people and investment into the city centre. The next stage of Birmingham‚Äôs regeneration ‚Äì the ¬£6bn pledged to such projects as the greenlit ∫√…´œ»…˙TV Schools for the Future programme, Edgbaston Hospital and New Street Station ‚Äì was dependent on Brindleyplace‚Äôs success.

Please don’t call the library an icon. This is nothing to do with my ego. It’s all about Birmingham

Francine Houben, Mecanoo

Houben’s ribbon leads back from Brindleyplace through the International Conference Centre to Centenary Square, where the new library will be built alongside Baskerville House, a listed thirties building. Originally there were concerns that the scale of the library would overwhelm its neighbour. Will there be trouble with the planners? “Well, I’m the head of planning,” Dutton says, “so, no.”

The one thing standing in the way of a through passage all the way to New Street station is the monolithic hulk of the 1974 Birmingham Library, a structure that still divides opinion among locals. The council wants to get rid of it as the sale of the land to Argent is dependent on its demolition. However, Hazel Blears, the communities secretary, may decide to list it, in which case the council could be obliged to refurbish it.

Dutton says such a move would be too expensive, costing as much as £150m, but adds that the Mecanoo library would go ahead “whatever happens to the old library”.

It may be then that Mecanoo’s red ribbon will be blemished by the old library, but it fits into the character of this architecturally unusual city. Gazing across the skyline, you see a panoply of incongruous buildings, from the bulbous mass of Future Systems’ Selfridges to the postmodern glitz of Ian Simpson’s Beetham Tower. Although both Houben and Dutton deny that Mecanoo’s library will be “iconic” – the head of planning and regeneration describes it as an “incident” building, whatever that means – it is yet another building type in a city that is already a cocktail of post-war design fashions. My walking tour concludes at New Street, the much maligned sixties railway hub on which Mace has been appointed to carry out a £600m redevelopment. This incoherent collection of forms is about to receive an architecturally uplifting upgrade. A bit like the city itself, in fact.

Postscript

Original print headline: 'Second city first'

No comments yet