Richard Griffiths moved from engineering to restoring historic structures, cutting his teeth on the derelict Old Dispensary in Stratford, east London. He recalls putting quality over cost, hostile workmen and an electric shock

I had been at Cambridge about two days when I realised that engineering was a big mistake. At school, my talents lay in the sciences, but my interests always sat more in the arts and I found I couldn’t face an entirely technical life.

I needed a path where I could make a bigger contribution to society and which had a cultural and aesthetic aspect. At first I found escape through singing and playing the bassoon in some fantastic locations such as King’s College Chapel, Ely Cathedral and the Snape Maltings arts complex. Maybe it was the sublime conjunction of great music and great architecture that helped me to find my eventual direction. My Damascene moment came at 3am one morning when I woke with a start and realised that I wanted to become an architect. So I started all over again. It was 1974.

At first, I was a rather undiligent student because I was so devoted to music but during my two years out I had a bit of a shock. Seeing things I had drawn being built made me realise that architecture was not just something abstract and I had better make up for lost time if I was to learn all the skills I needed. Architecture is physical and it affects people’s lives. You can go to an opening and, glass of wine in hand, look at something you created and see it being used and enjoyed. That was an extraordinary sensation. It was fantastically rewarding.

Julian Harrap was the pre-eminent architect in his field

I became very interested in the new buildings going up in Cambridge at the time but right from the start I knew that I wanted to work at the interface between old and new. In 1986, not long after completing my studies, I moved to London to join Julian Harrap’s office. He had worked for James Stirling, initially as a model-maker, before making a conscious decision to work with old buildings. He cut his teeth rebuilding the houses in Spitalfields saved by Dan Cruickshank and others following the battle of Elder Street. In my opinion, Julian was the pre-eminent architect in his field.

Instead of an interview, he took me to two of his projects to gauge my reaction. The first was Samuel Sanders Teulon’s St Mark’s church in Silvertown, burnt out in a fire. The re-roofing of the Victorian building with a continental chevron pattern of grey and green Westmorland slates, and the picking out of the chambers of the rebuilt trusses in red, made a great aesthetic impact.

Next, we climbed the tower of St Anne’s Limehouse, a church built in 1730 by Nicholas Hawksmoor. As we stepped into the roofspace and switched on the lights, the alternation of 19th-century restorer Philip Hardwick’s timber trusses and Julian’s new steel trusses painted in a blue-grey colour was suddenly revealed. Rarely have I received an aesthetic thrill more acute.

From here, we would plot the saving of historic buildings in east London

Technically, the design was brilliant too, the new trusses having been inserted piece by piece into the roofspace and then bolted together, without any scaffolding or propping. Their weight was no greater than that of the slates of the bay of the roof that had been removed. This was architecture to which I could relate, combining old and new, and harnessing technical ingenuity to aesthetic ends. I felt that I had arrived.

Each day, I would cycle to the office behind a Turkish watchmaker’s just north of Dalston, then a byword for gang warfare, and enter via a yard shared with an incontinent dog. From here, we would plot the saving of historic buildings in east London, almost all in an advanced state of dereliction.

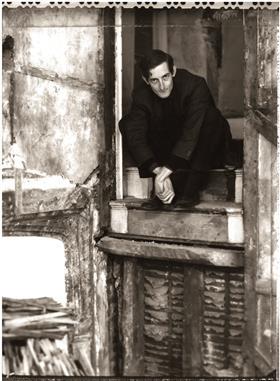

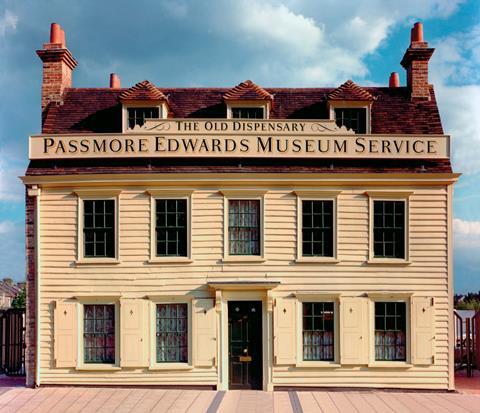

My first project was the repair and conversion of the Old Dispensary, a timber-framed Georgian clapboard house just east of Stratford town centre, into offices for the local museum service. The whole area was being redeveloped and suddenly funding became available. The practice had previously done a sketchy feasibility study for it – suggesting a rear extension you couldn’t access from the main building – but I started again from scratch. I designed the extension, which needed to contain kitchens and loos, as a subliminally classical building sitting below the cornice of the rear elevation, linked by a tall vertical window. This allowed the house, with its 18th-century timber panelling, to be restored and refitted as offices without being subdivided.

It was extraordinary that the building was still standing because it was fantastically derelict, to the extent that the corner posts had been cut off 3m above the ground, the timber sole plate had rotted away entirely and the frame was propped up on wobbly piles of bricks. It was all boarded up and I remember the musty smell and gloom as I walked in. The staircase had collapsed and there were holes in the floor where archaeologists had been trying to find evidence of a Roman road.

They were awkward cusses, who would raise their eyebrows sullenly

The whole thing was a wonderful learning experience. Because the client was the local authority, we had to use a contractor from their approved list, which meant I faced total incomprehension at first from the carpenters who were used to knocking up partitions for housing estates. They were awkward cusses, who would raise their eyebrows sullenly. But I would explain what I wanted and remain immune to their hostile glances.

The wonderful thing about working for Julian was that the priority was always quality and not money. About two-thirds of the way through the job, I realised that I had won them round as it dawned on them that they had created something exceptional.

The project was also an object lesson in how crucial the design of heating and lighting is. We had chosen electric radiant heating panels above the ceiling as an invisible and economic solution in conjunction with full insulation of the timber frame. Indeed, we won a low-energy award.

But just before practical completion, one of the workmen got quite a serious electric shock when he touched a metal architrave bead between a door frame and a light switch. The metal lath supporting the plaster had punctured the electrical heating mat and we realised that it could happen again because timber buildings move. I had a fairly sleepless night but, at that stage in your career, you have the confidence of youth. You don’t have the worry one does as a sole principal.

I had to convene a meeting the next day and explain how all of us could be held negligent if the matter went to court. The only solution was to abandon the existing installation entirely and replace it with radiant heating panels under the wooden floorboards instead. Fortunately everyone agreed and we managed to complete the project only two weeks late.

I learned an enormous amount, partly to do with maintaining relationships on site and the importance of teamwork. You also have to really understand the techniques and materials and what is achievable. I found it fascinating. It taught me something that I still come back to now: that working with old buildings is just as much a matter of architecture as designing new buildings, but with the added challenge of dealing with the layers of history and the texture of age.

Richard Griffiths is the founding director of Richard Griffiths Architects, whose conservation projects include Southwark and St Albans cathedrals, St Pancras Renaissance Hotel and Toynbee Hall in east London. He was speaking to Elizabeth Hopkirk

1 Readers' comment