The site of the notorious Maze prison was going to be the symbolic location of Northern Ireland‚Äôs showpiece stadium and a ‚Äėconflict transformation centre‚Äô. Now, after five years work and ¬£5m spent, the plan is set to be scrapped.

It was supposed to be the project that drew together the communities of Northern Ireland: a 38,000-seat stadium and conflict resolution centre, built on one of the bitterest sites in its history. But instead, plans to turn the Maze prison into a symbol of the end of the Troubles have achieved the impossible: they have further polarised the province.

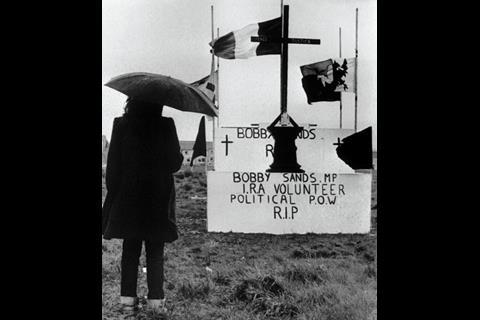

The first problem is the Maze itself. In 1981 it was the site of a hunger strike by IRA and INLA prisoners in which 10 of them died. This has led Unionists to denounce the £240m stadium and the conflict centre as a shrine to Republicanism. They want the project to be built in Protestant east Belfast, which has drawn a predictable reaction from the Catholic community.

Now, with £5m already spent, stakeholders on all sides of the argument expect Peter Robinson, who on 2 June took over from Ian Paisley as Northern Ireland’s first minister, to scrap the stadium any day now. It might even have happened by the time you read this.

The nightmare of history

Nine miles south of Belfast, HM Prison Maze was opened in 1976 as a jail for paramilitaries. Throughout the eighties and nineties, it housed some of the most notorious figures on both sides of the sectarian divide, including the Ulster Defence Association‚Äôs Johnny ‚ÄúMad Dog‚ÄĚ Adair and the IRA‚Äôs Sean Kelly, who tried to assassinate him by blowing up a chip shop full of civilians on the Shankhill Road.

The Maze was closed in 2000 after the Good Friday Agreement, and in 2003, it was announced that a government taskforce would look into regenerating the site. Three years later it unveiled a masterplan, complete with 38,000-seat stadium, also to be known as the Maze, and the conflict centre. Demolition started in October 2006.

David Hanson, then a Labour minister at the Northern Ireland Office, said: ‚ÄúThe Maze has long been associated with conflict. Clearing the site will be part of the mission to transform it into a symbol of economic and social regeneration, renewal and growth.‚ÄĚ

All set to go

Plans for the stadium and the centre are well advanced. HOK Sport and Mott MacDonald have been selected as stadium designers, and a shortlist of consortiums led by Laing O’Rourke, Sisk Group and Bovale Developments has been drawn up for the development partner role. The race to win the design for the conflict centre was contested by architects including Daniel Libeskind and Studio Egret West.

It is understood that winners in both these categories have been chosen, but that ministers were waiting until a definite go-ahead was given before informing the successful teams. Now we may never know who won.

Richard Grover, a project manager for Davis Langdon, the lead consultant on the Maze proposals, said that it would be a great shame: ‚ÄúA lot of work has gone into these bids.They‚Äôve spent six months working them up in the expectation that the project would go ahead.‚ÄĚ

The intention was to create a meeting place and educational centre where people could learn about how Northern Ireland made the journey from the dark days of the Troubles to the power-sharing agreement of today. David West, the co-founder of Studio Egret West, quoting from the bid document, says: ‚ÄúThey wanted ‚Äėa design that would be a sustainable symbol of peace and a catalyst for a society moving from division towards a shared future‚Äô. It was quite inspirational.‚ÄĚ

The practical objections

So how did the executive go from shortlisting development partners less than six months ago to giving the project the thumbs down now? The answer can be found in two reports, one prepared by PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) in March and the other by Drivers Jonas in April. Both give compelling reasons against building at the Maze.

The PwC report, commissioned by the executive, totted up the costs of building a stadium and found them to be about ¬£100m more than had been estimated ‚Äď a total of ¬£126m for the stadium, and ¬£114m for surrounding infrastructure.

According to Grover, this would be a difficult figure to justify. ‚ÄúThere are only 2 million people living in Northern Ireland,‚ÄĚ he says, ‚Äúso a contribution of ¬£100m would represent roughly ¬£50 per person.

If you had the same thing in the rest of the UK, ¬£50 a head would be the equivalent of a stadium worth ¬£2.45bn. Going ahead would be a big decision.‚ÄĚ

The Drivers Jonas report was commissioned by Belfast council and looked at the comparative regeneration benefits of building at the Maze compared with Belfast city. There was no competition, according to Brian Thompson, the partner in charge of the six-month research project.

‚ÄúOn everything ‚Äď commercial use, accessibility, transport, and sustainability in particular ‚Äď Belfast came out top,‚ÄĚ he says. ‚Äúļ√…ęŌ»…ķTV at the Maze would cut across so much government policy on where stadiums should be located in terms of accessibility regulations and carbon footprint. Every case study we had showed the capacity for regeneration is far greater in a city-centre location.‚ÄĚ

Thompson adds that he quoted Rod Sheard, design principal of HOK Sport, in his submission to the council. Sheard once said that to find the ideal location for a stadium you choose a city, stick a pin in the centre and find the nearest available site. ‚ÄúIronically, his team was the one that designed the Maze stadium!‚ÄĚ laughs Thompson.

This is a view shared by David Burnside, an Ulster Unionist assembly member He says the capital would be the obvious choice. ‚ÄúIn terms of economic viability and commercial sense, the only place for a national stadium is Belfast city centre,‚ÄĚ he says. ‚ÄúNobody wanted to build Wembley in Northampton.‚ÄĚ

Drivers Jonas was asked to isolate five city-centre sites that could be used for building a stadium. It duly found them, and sent the findings to the executive. Drivers Jonas has now been asked to narrow down its search to one single preferred site in a city-centre location with a fairly equal balance of Protestants and Catholics.

The centre becomes what it’s about

The two reports were compelling enough, but the practical arguments against building at the Maze were equalled by political difficulties over plans for the conflict centre. Ironically, a building to promote peace caused considerable conflict in the halls of the Northern Irish assembly.

The Ulster Unionists‚Äô Burnside says that the idea of the conflict centre was bound to be cause strife, and should have been taken out of the original proposals. ‚ÄúThere could be a good sporting complex of some kind at the Maze, we‚Äôve no problem with that,‚ÄĚ he says, ‚Äúbut it is completely ludicrous to bring in something that some people will think of as a memorial to the Troubles.‚ÄĚ

Martin McGuinness, the Sinn F√©in deputy first minister, has denied that a conflict centre at the Maze would become a memorial to the prisoners who died there. ‚ÄúI‚Äôm not arguing for a shrine,‚ÄĚ he told assembly members earlier this year. ‚ÄúIf we want a conflict transformation centre, then it has to focus on how we resolve conflict.‚ÄĚ

Sinn F√©in has not said whether it will push for the centre without the stadium, but it has made clear that it will veto a Belfast location for it. But if there is to be no stadium at the Maze, what will be built? The government owns the 350 acres of land surrounding the prison, and parties on all sides of the argument agree that redevelopment is vital for the area. Burnside says a motorcycle racetrack, a showground for equestrian events and an agricultural centre are all possible. ‚ÄúSomething will be built there,‚ÄĚ he says. ‚ÄúThere‚Äôs no doubt of it.‚ÄĚ

Whatever happens, it will only add to the money the government has spent on preparing the scheme, which is estimated to stand at ¬£5m. Burnside seems unfazed by the figure. ‚ÄúThat‚Äôs what governments do,‚ÄĚ he says. ‚ÄúThey spend money on consultants rather than making their minds up.‚ÄĚ

That money has been good news for companies such as Davis Langdon, but Grover sounds genuinely sad that the stadium will never be built. ‚ÄúPeople have put their heart and souls into this project,‚ÄĚ he says. Grover is one of the few to have analysed in any detail the three bids for the development partner role. ‚ÄúNobody wants to see a shopping mall or sheds.They could have built something wonderful.There were some fantastic ideas in the bids. But at the end of the day, nobody ends up with anything.‚ÄĚ

And when Peter Robinson’s final decision is made, the people of the six counties will be just as far from freeing themselves from the mentality of the Troubles as they ever were.

Timeline

2000 Last prisoners leave the Maze after the Good Friday Agreement

2002 Government sets up a regeneration body to examine the redevelopment of the 360-acre site

March 2004 End of public consultation into a stadium

March 2005 After three years of debate, proposals are put forward for 38,000-seat stadium

Jan 2007 Mott MacDonald and HOK Sport are commissioned to design it

April 2007 Laing O'Rourke, Bovale Developments and MLK Regeneration shortlisted as development partners

June 2007 Design competition launched for conflict resolution centre

February 2008 Report by Pricewaterhouse Coopers reveals price of stadium has risen but concludes building at the Maze would be 'best option'

May 2008 Department of Finance officials deliver internal business case to finance minister Peter Robinson, who says the executive will make adecision ‚Äúby the end of the month‚ÄĚ

No comments yet