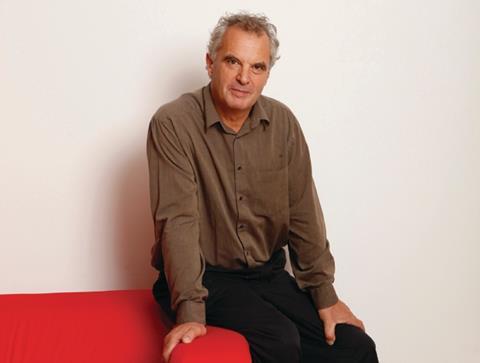

When Mark Whitby retired last year, everyone but him knew it wouldnât last. But after a year working on his garden, heâs finally seen the light ⊠Emily Wright met him as he prepared to open his new venture

Mark Whitby has realised that early retirement isnât for him - a revelation that will come as little surprise to anyone who knows him. When the 60-year-old left structural engineer Ramboll Whitbybird a year ago, his colleagues, clients and contemporaries all predicted that the industry hadnât seen the last of him. âItâs too early,â said one client. âMark has so much more to give and he is so easily bored. He is too young to retire.â âThis wonât last long,â said another. âHeâll be back. He is way too creative to be retired.â

They were right. Whitby is back with a new company, +Whitby because, as predicted, he did get bored. But Whitby himself seemed to be the last to realise this. âDo you know what? Thereâs only so much gardening one can do,â he says. He is referring to his year of âgardening leaveâ, which will culminate in him opening his garden up to the public next June. âThatâs not bad going is it?â he says. âBut I realised something. I am not going to spend the rest of my life being a gardener.â

To that end, he has set up +Whitby with his old friend Des Mairs, the same partner he had when he set up Whitbybird in 1983. By the time the business was sold to Danish engineer Ramboll in 1997 it was turning over ÂŁ40m a year and continued to thrive under its new appellation, Ramboll Whitbybird. The challenge this time round is not only to repeat their previous success, but to use their experience to make it even better - not the easiest of tasks in the middle of a recession.

Whitby had strong ideas about what he wanted to achieve when he set up his first business and now, with decades of experience, he has even stronger ideas. First off, he wants no part in running it. âI donât want to see a single set of accounts,â he says. âI am doing this so I can go back to designing. We are bringing in two younger people from Ramboll who are as keen as mustard to run the business. They are joining in November and December and I wonât be supporting them by running the business. This time they will be supporting me so I can do what I enjoy. When we were Whitbybird my job was five-sixths admin - this time I want to get back to engineering. I want to be at my desk with a pencil.â

Another reason for stepping back from the business side is because he wants to make sure there is a succession plan in place. âBoth these guys are about 40 years old and you need people who wonât just be around for a year or two, but until 2015 at least.â

So he doesnât see himself making another departure in the next five years? âNo, not at all,â he says. âI see myself being around until 2015 certainly. 2020 even. But I donât want people to be relying on me.â

The plan of action

The future of this new business wonât be resting solely on these two young guns from Ramboll, though. Whitby says they will be looking to grow the firm, hopefully to 10 people by the end of this year and to 20 by the end of 2011. This is quite a change from how Whitbybird grew. âWe really rode a tiger with Whitbybird,â he says. âWe grew so fast - 20% per annum and we had over 900 people by the time we finished.â He adds that +Whitby will be looking to hire the same kind of people, though. But, he emphasises, good doesnât necessarily mean Oxbridge. âBack then, we werenât just interested in first-class honours people,â he says. âWe would love the best out of a university like Paisley, which was in a phenomenally rough part of Glasgow. The engineering college there would often take technicians and turn them into engineers. These are people who may have had run-ins with the law. And those people are now serious directors at major QSs.â

Really? Whitby realises he is on awkward territory and moves swiftly on. âWe donât only take Cambridge grads,â he says. âWe love a cross-section of engineers, particularly those with interesting life experience.

â So, hiring a range of people from different backgrounds is one thing Whitby looks set to do again. But what will he do differently?

âWhat weâre not going to do again is services engineering,â he says. âJust structural engineering. We were multidisciplinary before, but we hope a specific focus will make us more money. Plus, it will be great to work with some old friends again. Our enthusiasm to work with certain people means we would find it difficult to turn them down.â

One thing thatâs certain is that it is a risky time to be setting up a new business. But Whitby says that with low overheads, no debt and such a wealth of experience, he isnât worried: âWe wouldnât be doing this if we didnât think it was going to work. We know lots of developers thinking about moving forward, and I really believe that after the Olympics things will look up pretty quickly. When we started Whitbybird we were in the middle of a minersâ strike and like back then, I think things can only get better. It may seem difficult to believe they will, but they will.â

He adds, though, that this wonât be the year for it, and expresses concern at the level of debt businesses are carrying. He says he believes the engineering industry is in a better position than others, however, because of a broader spread of work.

When we were Whitbybird my job was five-sixths admin - this time I want to get back to engineering. I want to be at my desk with a pencil

Then and now

And what of Whitbyâs personal change over the past 17 years? How different is he now compared with when he and Mairs set up Whitbybird? âI am a lot calmer now,â says Whitby. Calmer? âYes. Calmer,â he repeats matter of factly. The response comes as something of a surprise because there are few characters in the industry more extrovert, more chatty or more wildly enthusiastic and excitable than Whitby.

He feels compelled to explain: âMy job was always to worry about what everybody else was worrying about and worry that they werenât worrying enough. If someone came in and said, âI am really worried about thisâ, my sense of relief was enormous because I could share it and get it sorted out.â

Thatâs a lot of worry in one sentence and thereâs more to come: âThere were plenty of people who didnât worry enough. In engineering we take on a huge responsibility. Will things stand up? Will it work? What we do isnât a blasĂ© exercise and people have in the past, and will continue, to get things wrong. Worrying that everything is checked and worrying that past mistakes wonât be repeated is a vital part of the job.â

He adds that itâs not when his staff make mistakes that he gets upset - itâs when the mistakes arenât learned from and are repeated. Even though he wonât be running +Whitby hands on, you get the impression this is a standard he will expect to be upheld.

And it is one he admits he has had to learn the hard way himself too - although, now that he thinks about it, there was a time he didnât take criticism of his own mistakes lying down. âI remember when I was young and working on site and my boss asked me why I was making twice as many mistakes

as everyone else. I replied: âBecause I am working twice as hardâ. He didnât say another word about it.â

No comments yet