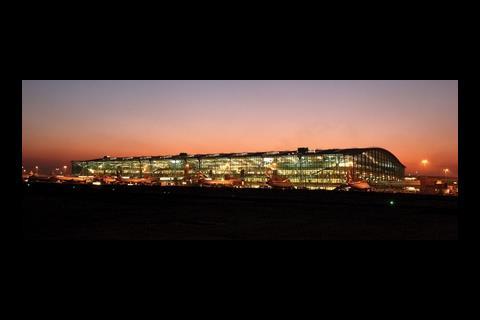

In the glory days of Terminal 5, BAA seemed to be leading construction into a new golden age of peace and prosperity. One takeover and a recession later, thatŌĆÖs looking unlikely. Dan Stewart assesses the future for a key client, and on page 42 we canvass two rather different views on HeathrowŌĆÖs third runway

One year on from the opening of Heathrow Terminal 5, it is clear that most of the claims made for it before it was built have been fulfilled. It was indeed a demonstration of what a modernised, rationalised, Eganised industry could do.

The famous T5 agreement gave BAA the project risk and integrated all 90 first-tier suppliers. Industrial relations were assured with lavish wages, excellent working conditions and bonuses to reward productivity: a skilled operative could earn as much as ┬Ż55,000 a year. BAA also worked with its main contractors to make the most of off-site manufacturing and state-of-the-art logistics. All of these initiatives showed a client that understood how enlightened self-interest required a different kind of construction process.

But one hope has not been fulfilled. The project was to mark the start of a new kind of industry, and BAA was take what it learned at T5 and use future schemes to show clients everywhere the wonders it could work. That prospect is now looking increasingly remote. Saddled with ┬Ż22bn of debt after its takeover by Spanish contractor Ferrovial in 2006, BAA is now focused on cutting costs; one senior source says: ŌĆ£Costs are too high and have to come down otherwise projects wonŌĆÖt be happening.ŌĆØ BAA may still be the industryŌĆÖs biggest client, but its attitude to the construction industry is looking decidedly ordinary.

WhatŌĆÖs in the pipeline

BAA has a forward construction programme of ┬Ż6.6bn, and although the Competition CommissionŌĆÖs ruling last week that it must sell off Gatwick, Stansted and either Edinburgh or Glasgow means that not all of the future projects at these airports will be run by BAA, the Civil Aviation Authority will still require them to be started (see box, below). What is more, those airportsŌĆÖ new owners will be required to carry on BAAŌĆÖs construction programme. Although there will be no requirement to use BAAŌĆÖs framework contractors, sources say that the operator has assured them it will do its best to ensure that they continue to do the work.

Heathrow, the airport that BAA will definitely keep, is by far the biggest recipient of its capital investment. The airportŌĆÖs current development plan, which runs from 2008 to 2013, has a budget of just over ┬Ż4bn. This includes the ┬Ż1.5bn East Terminal phase one, which is to be built by Ferrovial and Laing OŌĆÖRourke, together with a series of smaller projects (see box, below).

This is the most important single project. A year ago, a former director of BAA, who did not want to be named, told ║├╔½Ž╚╔·TV that the ŌĆ£key indicatorŌĆØ in understanding how the company would operate in future would be Heathrow East, also known as Terminal 2a. Those were ominous words, because the project has fallen behind. The disastrous opening of Terminal 5 meant that plans to empty Terminal 4 had to be delayed, and that meant the demolition of that building, required before Heathrow East could be built, has been delayed for six months, from March to October this year.

Sources close to the scheme predict that the opening of the first phase of Heathrow East, originally planned as a gateway for the 2012 Olympic Games, will not be possible until the end of 2013 at the earliest.

Phil Wilbrahams, project leader for Heathrow East, cannot yet confirm an opening date for the first phase of East. He says: ŌĆ£We still donŌĆÖt have a fixed plan. If you look back to T5, we only determined a completion date when we were six months into that programme, so weŌĆÖre not ready for that yet.ŌĆØ The only commitment he would give was that HeathrowŌĆÖs entire ┬Ż4bn construction programme would be complete in 2013/14.

Plans for a third runway and sixth terminal at Heathrow have been approved, but have attracted a level of opprobrium worse than that levelled at T5

Wilbrahams says the two years after that will be critical to deciding how much BAA will spend on Heathrow during its five-year plan. This will, in part, depend on how much it gets from the sales of Gatwick and Stansted. But he adds that there is plenty for the construction industry to do before then. ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖll be building Heathrow East phase two, which will increase the building to the size of T5. There is potential for a further satellite pier, or a terminal pier. There are also plans to further refurbish Terminal 3, which may include a new pier, and improve the transportation system,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£And of course there is the third runway.ŌĆØ

Plans for a third runway and sixth terminal at Heathrow have been approved by the government, but they have already attracted a level of opprobrium worse than that levelled at T5. At the very least, they will be subject to a lengthy public inquiry, and Boris Johnson, the mayor of London has said he will fight them in court.

Wilbrahams concedes that a third runway will be unlikely to be completed during the 2013-18 period ŌĆō ŌĆ£There is quite a process to go through before we can consider a timeframe,ŌĆØ he says ŌĆō but adds that there will be plenty of environmental, architectural and infrastructure work to pave the way for its construction.

The new dispensation

But despite the obvious opportunities, with Gatwick and Stansted sold, and BAAŌĆÖs Scottish airports unlikely to warrant redevelopment on a grand scale, it is unlikely that there will be as much work for BAAŌĆÖs supply chain as there was before, and this is contributing to its present drive for efficiency and reduced costs. This drive began after it was bought by Spanish contractor Ferrovial in June 2006, a deal that left it with about ┬Ż22bn of debt. Since then it has made a ┬Ż1.3bn loss, thanks to a massive writedown of its property portfolio as the economic crisis worsened. Although Ferrovial refinanced its debt last June, the burden weighs heavy on BAAŌĆÖs ability to spend money with the confidence it did on T5.

Sources close to the company predict that, before the end of 2009, BAAŌĆÖs complex built integrator framework ŌĆō the framework of nine contractors that carry out its major building projects ŌĆō could be reduced.

One says: ŌĆ£Even though about 70% of BAAŌĆÖs work is at Heathrow, there wonŌĆÖt be enough work for nine companies. The framework will be cut back to four or five.ŌĆØ

In fact, the role of this framework is already changing. BAA, which on T5 had a large team of in-house construction staff overseeing work by main contractor Laing OŌĆÖRourke, let more than 200 project managers go in January 2008.

As a result, the main contractors now run BAAŌĆÖs main projects without continual guidance from the clientŌĆÖs in-house team; rather they have reverted to the traditional clientŌĆōcontractor relationship rather than one where the client was acting as a construction manager.

These are difficult times. WeŌĆÖre committing to spending this money, but we are going to spend it more wisely

Phil Wilbrahams, BAA

Wilbrahams acknowledges the shift: ŌĆ£On T5, BAA had more than 100 first-tier suppliers, and we were managing all those relationships ourselves. WeŌĆÖve worked with these guys for a long time and weŌĆÖre now in a position to get the right people managing the right risks.ŌĆØ

In addition to the departure of the project managers, the stream of senior departures that began shortly after Ferrovial bought the company has continued. This means that most of those with experience of the construction processes on T5 have now left. Andrew Wolstenholme, the head of capital projects, left in October to head Balfour Beatty Management. Other high-profile figures to leave in recent months include David Bartlett, the head of design, who moved to Lend Lease in December.

The consultantsŌĆÖ frameworks are due to be retendered before the end of the year, and it is likely that these will also be reformatted to address the ŌĆ£new realityŌĆØ of how BAA works. According to one source, ŌĆ£It will have a different emphasis. It will be much more geared to deliverability and value for moneyŌĆØ.

In another change, sources close to the company say the Major Projects Agreement (MPA), which offered generous rewards to productive electricians, is unlikely to ever be repeated. ŌĆ£It will never do that again ŌĆō not with the debts itŌĆÖs got, and certainly not during a recession,ŌĆØ says one source. ŌĆ£Laing OŌĆÖRourke tried to sell the MPA to projects in Ireland and in the Middle East, but it never took off. ItŌĆÖs dead in the water.ŌĆØ

Finally, the Ferrovial takeover may also throw up some additional problems for contractors. There have been persistent rumours of tensions between Ferrovial and Laing OŌĆÖRourke, who are building Heathrow East terminal together. The Spanish contractor, which controls 65% of the joint venture, took the designs by Foster + Partners and handed them to its own executive architect for value-engineering. Laing OŌĆÖRourke was understood to have been left out of the process.

Silver lining?

Although BAAŌĆÖs less evangelical, more practical approach is unlikely to win many plaudits from those who hoped it would continue to pilot the reform of the construction industry, there are some beneficial effects for the industry.

Mike Peasland, group managing director at Balfour Beatty, one of the firms on the complex-build framework, says the hands-on approach BAA used on T5 is unnecessary now that its main contractors have proved their methods of working are reliable. ŌĆ£BAA is not self-contracting, which is what it did before,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£Its main contractors know what theyŌĆÖre doing, so it will let them do it. It has become an intelligent client, rather like Network Rail and the Highways Agency.ŌĆØ

Wilbrahams is also keen to stress that the client is not going to ignore its construction responsibilities. ŌĆ£Look, weŌĆÖre not going to just turn our backs on our work. WeŌĆÖll be taking a full client role [on Heathrow], it will just be in a different way to T5. These are difficult times. WeŌĆÖre committing to spending this money, but we are going to spend it more wisely. There is the opportunity for us to do things cheaper and faster. We are still dedicated to this industry: ┬Ż800m a year is a significant workload in anyoneŌĆÖs books.ŌĆØ

There is also the possibility that the drive for efficiency could lead BAA to more innovations. Colin Matthews, its chief executive officer, gave a hint of this in a speech to the Movers and Shakers breakfast in London last week. He said: ŌĆ£We want to raise professional standards and cut costs by better quality design and by the integration of construction and design. We need to be doing it better and more cost-effectively than before.ŌĆØ

What is BAA building?

Heathrow ŌĆō total of ┬Ż4bn from 2008-13

Heathrow East (also known as Terminal 2a) phase 1 ┬Ż1.5bn

Heathrow Eastern Campus improvements ┬Ż750m

Heathrow East midfield pier (also known as Terminal 2b) ┬Ż500│Š

Terminal 5c satellite pier ┬Ż300m

Terminal 4 refurbishment ┬Ż190m

Terminal 3 refurb/extension ┬Ż120m

Stansted ŌĆō total of ┬Ż1.4bn from 2008-2013

Upgrade of terminal and new pier ┬Ż500│Š

New runway (subject to approval) ┬Ż900m

Gatwick ŌĆō total of ┬Ż874m from 2008-2013

North Terminal extension and South Terminal upgrade

Who builds for BAA?

The contractors on its main framework are Balfour Beatty, Carillion, Costain, Ferrovial Aggroman, Laing OŌĆÖRourke, Mace, Morgan Ashurst, Skanska and Taylor Woodrow

1 Readers' comment