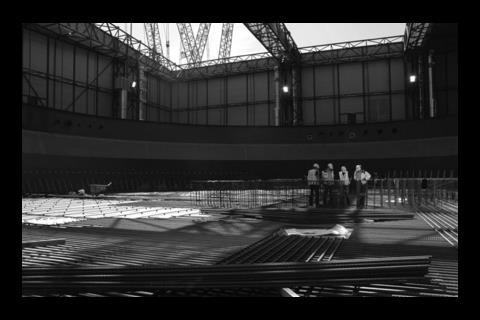

Work has started on Europeâs third generation of nuclear power plants. Problem is, the firms building them are finding it much harder than expected â the Finnish plant in this picture is three years late. Thomas Lane finds out what this means for the UKâs own nuclear plans

Work on Europeâs third generation of nuclear reactors is not going to plan. The first plant is being built in Olkiluoto in western Finland. It was meant to start operating next year, but the present estimate is that it will not be ready until 2012 at the earliest. It will also cost at least 50% more than was originally thought. Meanwhile, at Flamanville in Normandy the same European pressurised water reactor is being built for EDF, and this is going the same way. Recent reports claim that it is nine months behind schedule â which does not bode well for a project that has been on site for barely a year.

For the British nuclear new-build programme, this has grave implications. The European pressurised water reactor, designed by Areva NP, is one of two designs being considered for the UK, which means any technical problems it might have are a concern for Britain, too. Furthermore, most of the problems in Finland and France have been caused by civil engineering work, which would be the same for the UKâs other option, Westinghouseâs AP1000. In Finland and France, this is the reponsibility of Bouygues.

The UKâs programme is due to begin in 2011 (see the timeline), and last week Balfour Beatty announced that it was joining forces with Areva to bid for it. The challenge they face is to find out why the problems have occurred, and how they can be prevented from messing up Britainâs nuclear programme.

On nuclear projects, contractors have to implement designs exactly, ensure that specification is spot on and adhere to stringent quality controls on site. âSafety and quality come first,â says Petteri Tiippana, assistant director of Finnish nuclear regulator STUK. âCost and the schedule donât come into it. There can be no short cuts, even if some procedures might not seem reasonable.â

The trouble is that contractors lack recent experience of building to these standards or meeting regulatorsâ safety requirements: no nuclear power stations have been built in Europe for more than 10 years. For a start, work on site cannot begin until the design has gone through a lengthy approvals process. And when it does get going, time is lost while the detailed design of particular components is worked out. In the UK, the Nuclear Directorate, the body that licenses new plants, is trying to crack this by approving generic designs, so minimal work will be needed to approve plans for specific sites. âWe can quickly get to a position to grant a licence for that reactor on that site,â says Mike Weightman, the chief inspector of nuclear installations and head of the Nuclear Directorate. âIt will lead to minimum regulatory risk.â

Then there are the technical issues. In Finland, concreting work stopped for two months in 2006 because the concrete mix contained too much water. The time was spent checking that the poured concrete would perform as intended, and the regulator had to be satisfied by the new quality control procedures before work could start again.

In France there were similar problems. The concrete slab at the Flamanville plant was poured in two stages because there was a limit to how much could be poured in one go. Unfortunately, the first pour stopped at a point at which there was no rebar to hold the concrete together, which caused cracking.

Thomas HoudrĂ©, who heads the regional division of French regulator ASN that is overseeing the work, says this was a design flaw. âThe contractor followed the design,â he says. âThis will be taken into account in the next project.â

In March, there was another problem. ASN discovered that some stirrups â hoops of reinforcing bar â were missing from the foundation base. âIt wasnât detected by the operator, which demonstrated that the control and surveillance on the site wasnât rigorous enough,â says HoudrĂ©.

Despite this, EDF failed to get its quality control regime up to the required standard. On 6 May this year, a subcontractor noticed that stirrups were missing from another area of the base and reported it. A week later another subcontractor reported that they had been installed. On 14 May, the day of the concrete pour, an EDF controller spotted that the stirrups had not been installed and asked the contractor to put them in before the pour, but this did not happen. âOn the morning of the 15 May we ended up with the base slab poured and the stirrups missing,â says HoudrĂ©. As a result, concrete pouring was suspended for nearly a month while the quality control regime was beefed up yet again, and the missing stirrups reinstated.

Welding quality on the steel containment vessel, which is intended to prevent nuclear contamination in the event of an accident, has also been a problem at both sites. In Finland, STUK found that the welds were substandard because of high humidity levels caused by workers wetting concrete nearby.

In February 2008, ASN discovered that the welders on the French project were not properly qualified and in June welding was suspended because it was not up to standard. Last month, ASN found the welding contractor was working from âvery general documentsâ and that conditions were too humid. Again ASN asked for quality management to be improved.

EDF says the project remains on schedule for completion by the end of 2012 and that it is normal that there will be âissues to addressâ on a development of this size. It adds that there were no issues that would have any effect on the safety of the plant, and that EDF and its suppliers had taken steps to improve quality control throughout the site.

The question is, since Bouygues is working on both plants, why are the lessons learned in Finland not being applied to France? Tiippana thinks this is because the Finnish job is being run by reactor designer Areva whereas in France operator EDF is in charge. âItâs not clear that they are exchanging information,â he says.

HoudrĂ© is more blunt. âASN has told EDF it should be looking more closely at the construction in Finland,â he says. He adds that he wants lessons learned in France to be formally documented so these can be passed to the next project.

Areva and Bouygues declined to comment.

This sharing of information is crucial for the future of nuclear construction. As Weightman points out, the nuclear supply chain is global rather than local, so quality issues are an international problem. âIf you have problems with one supplier it undermines confidence in the nuclear industryâs ability to supply products to time and cost,â he says.

He thinks the industry needs to form an association of approved suppliers rather like the world association of nuclear operators. âIf the UK can sustain excellence in what they are doing they could get ahead in the international market,â he says.

Tim Stone, the governmentâs senior nuclear adviser, says the problems that have occured on the French and Finnish plants are not severe. âItâs a basic construction issue,â he says. âThe trouble is, the guys doing it forget itâs a nuclear site â to them itâs just another slab of concrete.â

He thinks there will be fewer problems when it comes to the installation of nuclear components, because the specialists involved have a better understanding of the work. Like Weightman, he thinks the generic design approval process will take care of any delays caused at the detailed design stage.

However, Tiippana maintains that the installation and commissioning phases are extremely challenging. He says that each time a new phase of the Finnish project has started there have been teething problems, and warns that project teams will have to prepare very carefully if they to want to ensure they meet the required quality standards and keep the project on schedule.

At whichever stage the problems lie, there are still plenty of lessons to be relearned. Letâs just hope they all are by the time work starts in the UK.

Original print headline - How do you build nuclear power stations again?

The problems in Finland

Work started on the 1,600MW plant in 2004. It is being delivered by a joint venture between French nuclear specialist Areva and German company Siemens as a turnkey contract with a fixed price of âŹ3bn (ÂŁ2.6bn). It was originally meant to come on stream in 2009 but the construction problems mean it probably will not be switched on until 2012. Reports say it will cost 50% more than the original budget.

February to March 2006

Concreting work is halted for eight weeks after the foundation concrete was found to be too wet. Work is checked and deemed to be of a sufficient standard, but regulator STUK insists on new quality control measures at the concrete batching plant.

July 2006

STUK issues a report saying the amount of time needed for the detailed design was seriously underestimated when the original schedule was agreed.

October 2006

The steel containment liner is blown off its supporting pallets and damaged.

August 2007

STUK orders welding work on the steel containment liner to stop for more than a month after it finds poor quality welds and deformations in the liner. STUK orders the deformed sections to be cut away and new ones welded in.

The problems in France

The French plant will produce 1,650MW when it is switched on in 2012. Like Finland, it is being delivered by Areva, but operator EDF is acting as its own architect and engineer. Bouygues is responsible for the civil engineering and the cost of building the plant is budgeted at âŹ3.3bn (ÂŁ2.9bn).

February 2008

A flaw in the rebar design leads to cracking in the reactorâs concrete base slab. The cracks are filled with resin.

March 2008

ASN discovers that stirrups are missing from the base slab.

May 2008

Concreting work is halted for almost a month after rebar elements in the concrete base are found to be missing. ASN asks EDF and Bouygues to improve their quality management system including using outside inspectors for the first time.

June 2008

Welding operations are suspended after defects are discovered. ASN then notices the welding isnât being carried out in accordance to the technical standards for nuclear work.

November 2008

ASN discovers that weldersâ quality control procedures are not up to standard and that conditions are too humid.

When can we start on site?

This is the UK governmentâs estimate of the time it will take to build a nuclear power station âŠ

Autumn 2009

Decommissioning work is completed on existing sites

Summer 2010

The planning process for individual sites begins. This is expected to take 18 months, although that depends on changes to the Planning Bill.

Spring 2011

The site-specific licensing procedure begins. This will be complete when an operator is granted a licence to build and operate a specific design on a particular site. The process for each site will take a year and will take place in parallel with the planning application.

Summer 2011

The Nuclear Installations Inspectorate

finishes its safety assessment of the two possible designs, the Areva NP European pressurised water reactor and Westinghouseâs AP1000. The idea is to get the detail design approved before work starts to save time

on site.

Spring 2013

Work starts on site. Each plant is expected to take five years to build so the first stations ought to start generating electribity in mid-2018.

1 Readers' comment