The death of the businessman just after Christmas recalls a bygone age in contracting

“Not a chap I knew, but a reputation as a real gentleman.”

For those that did know him, the passing of Sir Martin Laing a couple of days after Christmas marks the end of an era. Even for those that didn’t, like veteran developer Sir Stuart Lipton, the name sparks memories of contracting in a bygone age.

The rollcall of jobs carried out by Laing is immense. The firm rebuilt the bomb-damaged Coventry Cathedral; it built the first stretch of the M1 – around 60 miles of road – in a little over 18 months; it constructed the Second Severn Crossing, the Sizewell B nuclear power station, a new airfield for the Falklands after the 1982 war. The list goes on…

Martin Laing, as he was then, was born in 1942, the son of Kirby Laing who, along with younger brother Maurice, turned Laing into a construction powerhouse and a household name after the Second World War. He became executive chairman in 1985, a post he held until the construction arm was sold 16 years later.

Most know the story of its decline, felled by losses on a series of jobs in the 1990s, such as the Millennium Stadium in Cardiff and the National Physical Laboratory in west London, which saw it eventually picked up for £1 in 2001 by concrete subcontractor O’Rourke, run by Ray O’Rourke.

“The deal of the century,” former Mace boss Steve Pycroft called it a few years ago. Not for everyone, though.

The story goes that a heartbroken Maurice Laing, who came up from the sites and did not go to university, unlike his Cambridge-educated brother and nephew, wrote a personal letter to Ray O’Rourke with a simple message: “Look after it.”

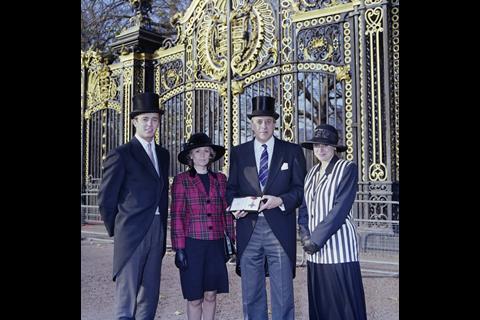

Sir Martin Laing, as he was known by now – having been knighted in the 1997 new year honours which also saw Paul McCartney made a knight of the realm – was the Laing family member in charge of the business when he sanctioned its sale to O’Rourke.

“Towards the end, it must have been pretty painful [for him],” says John Armitt, who worked at Laing between 1966 and 1993, ending up as the chair of its international business and, after Stuart Doughty left, boss of the firm’s civils division.

“He knew Ray very well because he was putting up their frames. I guess it was easy for him [O’Rourke] to come along and make a proposal.”

Bernard Ainsworth, who worked at Laing for 34 years before leaving in 2002, a year or so after O’Rourke’s deal for Laing was concluded, adds: “Ray always wanted to buy Laing. He looked up to it as a company.”

He described himself as an entrepreneur and he was always pushing new ideas

Sir John Armitt

While other famous marques have disappeared – Mowlem, Alfred McAlpine and Wimpey to name a few – the Laing name has remained. “[Ray] knew the value of the brand,” adds Ainsworth, whose last major job at Laing was overseeing the Millennium Dome, now the O2, which it built with Sir Robert McAlpine.

For Armitt, who later went on to head up Costain and Network Rail before being appointed to chair the Olympic Delivery Authority, created to build the 2012 Olympics in London and who is now the head of the National Infrastructure Commission, Martin Laing was the front man for the business.

“He used to call me one of his grey men,” Armitt remembers. “He described himself as an entrepreneur and he was always pushing new ideas.

“He was very much front-end. He liked finding the opportunities and building relationships rather than the sharp end of site management.

“He was always enthusiastic about opportunities. I never got any pushback from him when we bid the job to build the airfield in the Falklands or the Second Severn Crossing.”

Ainsworth, who started as a production controller, “the oik to the site manager” eventually becoming director of Laing Management, adds: “Martin left the day-to-day running to his lieutenants. Maurice and Kirby were more hands-on.”

But Martin Laing would step in when he needed to, to become that face of Laing described by Armitt when required.

Ainsworth, who went to work on the Commonwealth Games stadium in Manchester and after that the Shard, recalls a story about how he and Martin Laing jumped in the Laing helicopter to fly up to Derby to present bid documents in person for the job to build a new car plant in the city for Japanese firm Toyota. “He delivered them personally to the Japanese,” he adds.

They won the job, with work starting in 1990. “He was very proud of [the company], we all were. It was a great business to work in.”

Stuart Doughty says that personal touch has been carried on by Ray O’Rourke, who has often led bids and made sure he has been there when the deal is concluded. Steve Pycroft made a point of doing this, too, notably on Mace’s scheme to build The Shard.

“This is hugely valuable, especially in the Far East and Middle East where these things matter,” Doughty says. “Martin played a very important role in that respect.”

He was very good at talking and communicating with the troops. He was the front face of the company

Stuart Doughty

Doughty, now a non-executive at Balfour Beatty and, like Armitt, a former boss of Costain, joined Laing in 1965, eventually leaving for Tarmac in 1987. He joined as a graduate engineer, starting as a general foreman on the Eggborough power station in North Yorkshire.

He arrived when Sir John Laing, Martin’s grandfather, was still there. “Back in those days, there was smoking in the office and girly calendars on the wall. There was none of that when he came around.

“Everyone stood up and to attention. They did that with Martin as well. The family was really well liked.”

He adds: “Martin was a delightful guy. At a formal do, you’d find him in a corner having a cigar and a whisky and talking. He was very good at talking and communicating with the troops. He was the front face of the company.”

John Armitt also recalls many times spent overseas – at one stage Martin Laing lived with his wife Stephanie in Cairo – in Martin’s company. “He liked a whisky and a cigar late at night, chewing the cud. I have lots of fond memories of him and the company.

“It was a privilege to be at a company like that. We had our own labour force, design team, kit. We owned everything.”

Others to pass through the firm included former WS Atkins chief executive Mike Jeffries, who joined the business as a 19-year-old in 1963.

“I joined as an unqualified and green architectural assistant. I was given the job of doing the drawings for an extension to Kirby Laing’s house close to their offices in Mill Hill, even though I had almost no prior training.

“On one occasion, visiting the property, I met Martin. But I left the company when I was 22 and I had no further contact with the Laing family after the extension was completed.”

He says the pair renewed acquaintance when he joined Atkins in the 1970s. “We were part of some overseas trade missions which Martin latterly led and subsequently in relation to consortium joint ventures between our two companies.”

His last dealings with him were on the Cardiff stadium job, where Atkins was the engineer. “He rang me to say that Laing thought that Atkins were being unreasonable in the way we were enforcing the terms of the contract and I intervened personally to ascertain whether this was indeed so. I had to report back to him that this was not the case – which he accepted.”

This kind of conduct, even when dealing with difficult contract disputes, was typical of the way that Laing people were brought up to behave, Doughty says.

“People did jobs right, there was a pride in working for Laing. All the people there were trained to do things right – and in the key tenants of life as well.”

Sir Martin Laing, born 18 January, 1942, died 27 December, 2023

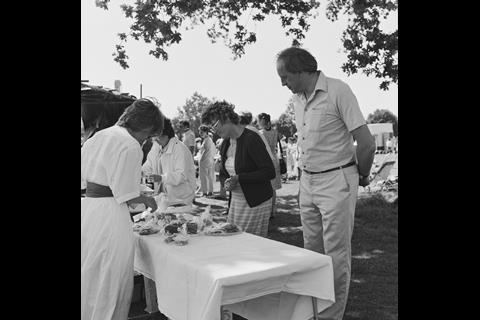

In 2012, John Laing gave its entire collection of 230,000 images to the government’s heritage adviser Historic England. begun by Historic England and the John Laing Charitable Trust.

All images Historic England Archive/John Laing Photographic Collection.

No comments yet