How project director Hiley climbed out of the £400m hole Bovis had got itself into on the hideously complicated joint hospitals scheme

The Manchester joint hospitals project will go down in history as one of the most complicated and expensive PFI schemes ever. The ¬£480m scheme involved rebuilding five big hospitals on a 44-acre site in the middle of Manchester, which made it the biggest single-stage, lump-sum design-and-build project in the world. The whole scheme consists of 6,800 rooms ‚Äď and to get this in perspective, it took someone a whole day to eyeball each of the 2,500 rooms in one of the hospitals.

The scheme will also be remembered for contributing most of a £48m writedown suffered by the northern division of Bovis Lend Lease in 2007.

The ideal solution to the renewal of the hospitals would have been to knock the lot down and build them on a new site. But as none was available in the area, Bovis had to build new facilities on the existing site, move in their occupants and rebuild their old home. Problem was, the site had evolved in a piecemeal fashion over 100 years and was a jungle of clinical buildings, car parking, energy centres and offices. Although most of the hospital is now finished, a walk around it gives you a good idea of the difficulties. There is a high-level service bridge linking two buildings that passes a few millimetres from the roof of an old biochemistry lab that has just been vacated ‚Äď the bridge‚Äôs column was piled and built a couple of metres away. Next door an old Victorian ward has been half demolished to allow the new hospital to be built; the broken-off ends are sealed up with plywood to allow it to continue operating.

What went wrong?

With the benefit of hindsight it is obvious that Catalyst, the PFI arm of Lend Lease, did not take into account all the things that could go wrong and bid too low. ‚ÄúPFI is the toughest contract in construction,‚ÄĚ says Graham Hiley, the Bovis project director responsible for turning the job around. ‚ÄúThis is a third wave PFI project; with each wave the NHS has got more sophisticated and tougher.‚ÄĚ Catalyst knew it was cutting things fine but it had spent a fortune bidding for the job and did not want to lose it.

So Catalyst was vulnerable to anything which pushed the cost of the job up. This included a year-long delay while the government changed the terms and conditions of former NHS workers who transfer to the public sector. Not only did the team spend a year twiddling its thumbs while this was thrashed out, it also meant that Bovis was hit by rampant construction inflation. The Manchester boom pushed up labour rates and material prices shot up, too, because of insatiable worldwide demand. ‚ÄúIt only takes a few per cent on ¬£400m to be a long way out,‚ÄĚ Hiley says.

But this is only part of the story. Once the job got going it began to suffer from horrendous delays. Straightforward stuff was not a problem; a car park built on a vacant plot was handed over early. But once the team started on buildings linked into the site-wide service supply, things started to go wrong. ‚ÄúWe discovered the condition of the existing services was much poorer than anticipated,‚ÄĚ says Hiley. For example, the team would try to isolate steam and water supplies to an area but found the valves were seized up. This meant shutting down the supply further up the line so the offending valves could be fixed. But Bovis could not go around shutting down essential service supplies wherever it felt like it. ‚ÄúYou have to apply to the trust to shut down the services and you might have to wait a month just to do the remedial work to get you back to the point you started with,‚ÄĚ sighs Hiley.

Asbestos was another big problem. ‚ÄúWe expected to find the asbestos lagging on the pipes but it was in such poor condition that it was falling off, so we couldn‚Äôt encapsulate it,‚ÄĚ says Hiley. ‚ÄúThis meant we had to seal off the affected areas and strip it all off, which equals a lot of time and money.‚ÄĚ Traces of asbestos were found in the roofspace of the nightingale wards, so it had to be carefully stripped out before they could be demolished.

By Autumn 2007 we had our heads down, bums up and were going for it

Graham Hiley

Six months into the job the team was behind on the mental health buildings and a heart and renal unit. ‚ÄúThe build programme was very optimistic for the early buildings because of all the service diversions,‚ÄĚ notes Hiley. This had a knock-on effect on the rest of the job. For example, the delay on the heart and renal unit meant the nightingale wards could not be emptied and demolished to allow work to start on the new eye hospital. ‚ÄúWe hadn‚Äôt even started demolishing the nightingales and we only had 18 months to hand the eye hospital over,‚ÄĚ says Hiley. The delays with the mental health buildings prevented work starting on the children‚Äôs hospital which by now was 40 weeks behind.

Things were getting so bad that Bovis had to take radical action. Jason Millett, the chief executive of Bovis at the time, wanted Hiley to take over the job but he was busy finishing another PFI hospital at Romford. ‚ÄúJason was desperate to get me up here but I said there was no point in creating two problems by pulling me out early,‚ÄĚ says Hiley. By now Peter Leaman, the original project director, had left so the job was placed in the hands of John Hyne, a caretaker project director who had been running the Scottish parliament job.

Hiley arrived in Manchester in July 2006. ‚ÄúThe project was overbudget, behind programme and the team were pretty low,‚ÄĚ he says. ‚ÄúOur relationship with the trust was horrendous.‚ÄĚ

What did Hiley do to sort out the mess?

Hiley says the first thing he did was establish the project‚Äôs financial and physical position so he could work out the best way forward. ‚ÄúWe had to draw a line in the sand,‚ÄĚ he says. ‚ÄúWe had to reset the programme to one that was tough but doable and restructure the finances so we had a budget that was also tough but realistic.‚ÄĚ

This exercise included looking at the strengths and weaknesses of the team and restructuring it. Some people had to go and Hiley brought in key members of his team from Romford. He also asked for the authority to do whatever was necessary to make the project work. By now Murray Coleman had replaced Millett and kept a close eye on the job, but he gave Hiley the authority to run the job as he thought fit.

Hiley recast the programme which meant changing the handover date for the eye hospital from October 2008 to June this year, the women‚Äôs hospital from January 2009 to May 2009 but amazingly, given it was 40 weeks behind, the children‚Äôs hospital handover date did not change. Hiley now had to sell the revised programme to the hospital trust. Unsurprisingly it was suspicious at first. ‚ÄúOnce they started to realise I was being open and honest with them they relaxed a bit,‚ÄĚ Hiley says. He persuaded them to provide an extra temporary ward which enabled Bovis to start work on one building earlier than originally planned. Hiley says it took six months to work out what needed to be done, and another six months for everyone to settle down and get used to the new regime. ‚ÄúBy Autumn 2007 we had our heads down, bums up and were going for it,‚ÄĚ says Hiley.

Did the strategy work?

We had to reset the programme to one that was tough but doable and restructure the finances so we had a budget that was also tough but realistic

Graham Hiley

This strategy has paid off as Hiley says he has delivered on all his promises. ‚ÄúThere have been 24 handovers in the past three years and every one has been on time,‚ÄĚ he beams. The past 10 months have been particularly frantic as all the big hospital buildings have been handed over during this period. Hiley says that when you are handing over 6,800 rooms, you have to start signing them off nine months earlier. ‚ÄúYou can‚Äôt leave it all until the week before the end,‚ÄĚ he says. ‚ÄúThat means every week we have to complete between one and two hundred rooms. That‚Äôs equivalent to 30 flats ‚Ķ none of the housebuilding boys have to deal with those sorts of numbers.‚ÄĚ

Picture of health: rationalising the hospital site

The first hospital opened on the site in 1902 and has evolved piecemeal over time. ‚ÄúThe existing hospital was all over the place; it was a labyrinth of corridors and buildings that have grown up in an unmanaged way over the past 100 years,‚ÄĚ says Bahman Tavacoli, the practice director of architect Anshen + Allen.

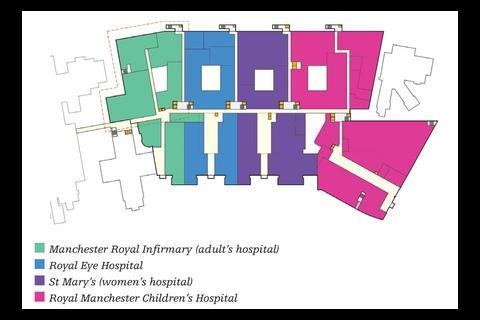

The plan was to rationalise the site and bring in two children’s hospitals located on remote sites. This would mean the site would contain a large children’s hospital, a women’s hospital, an eye hospital and an adult general hospital. There are also child and adult mental health services and outpatient facilities.

The existing adult hospital, the Manchester Royal Infirmary, would be retained and extended but the existing women’s hospital, St Mary’s, would be demolished once the new building was completed. Several listed buildings to the south of the site would be retained and refurbished as administrative buildings. If that were not enough, the top three floors of the new hospital contain high-level research facilities.

The four big hospitals have been arranged within one large building at the north of the site. The existing adult and new mental health buildings are located on either end of the new building. A plaza has been inserted between these and the existing buildings on the south end of the site. ‚ÄúThis layout also gives the site clarity, which was one of the most important factors in the trust choosing our design,‚ÄĚ says Tavacoli.

The arrangement does make the site legible. Patients arrive in the plaza and can enter the relevant hospital through its own dedicated entrance ‚Äď in the case of the children‚Äôs, eye and women‚Äôs hospitals, these open into a large, airy atrium. An internal ‚Äústreet‚ÄĚ runs the entire length of the building at each level, and each hospital is colour coded so people know where they are. Ambulances and service vehicles use a service road to the north of the new buildings, the facilities management and energy centres, are located on the other side of the road.

All the hospitals will be operational by August but the job still has 15 months to run. St Mary’s hospital occupies one end of the plaza and has to be demolished. Numerous other smaller buildings occupy the plaza and will be demolished, too. This central area will then be landscaped.

It only takes a few per cent on £400m to be a long way out

Graham Hiley

The Hiley philosophy

Graham Hiley is a Bovis man through and through. He joined the company in 1978 and apart from a brief spell working for a medium-sized contractor as a site manager, he‚Äôs been there ever since in a variety of roles. These include a stint as contracts manager in the Marks & Spencer division of Bovis. Hiley says they were a demanding client. ‚ÄúYou never handed a project over late or overbudget,‚ÄĚ he says. ‚ÄúIf they asked for an extra floor on a building without changing the completion date, you just did it.‚ÄĚ

Hiley also spent some time in the special projects division road testing a variety of contract types. His first brush with a hospital was the redevelopment of St George’s hospital on Hyde Park Corner into the Lanesborough Hotel. He’s done shopping centres and offices and run the commercial division of Bovis in London and the South-east. He has also done 13 Tesco supermarkets, the Crossrail station box at Paddington Central and Romford Hospital, his first public sector project.

What is the Hiley philosophy of successful project management? He says the trick is to not be daunted by the scale of big projects but to break them down into manageable chunks. These are then given to someone to look after all the way through. ‚ÄúThe big thing is to give people responsibility, accountability and ownership for their section of the job,‚ÄĚ he says. ‚ÄúPeople work better if they know their boundaries.‚ÄĚ

Hiley‚Äôs role is more strategic; he liaises with senior Bovis management. ‚ÄúI‚Äôm a strong advocate of the management team owning the programme,‚ÄĚ he says. ‚ÄúIt‚Äôs up to the construction management team to work out the best way of implementing the strategy, although they don‚Äôt do this in isolation.‚ÄĚ

Careful specialist contractor management is also key to timely project delivery. He schedules monthly meetings with the directors of specialists. ‚ÄúThere‚Äôs a tendency for them to slacken off at the end because they think they have less to do than actually remains to be done,‚ÄĚ he says.

All the packages are monitored to check the work is up to standard.

‚ÄúIt‚Äôs about detail and proper validation processes and ensuring everything is done in order,‚ÄĚ says Hiley. ‚ÄúIt‚Äôs very disciplined with regimented sign-offs. You don‚Äôt accept what subcontractors say, you always check their work and assume it will need snagging even though it‚Äôs all signed off.‚ÄĚ

Postscript

Original print headline: ‚ÄėThe project was overbudget, behind schedule, the team was low and our relationship with the client was horrendous‚Äô

No comments yet