Yes, itâs on again, folks â the rescue and renovation of one of Londonâs most famous landmarks, that is. This time itâs Treasury Holdingsâ turn to make what it can of the art deco power station. Thomas Lane looks at the scale of the job and the chances that this time, finally, something will come of it. Photographs by Matt Livey

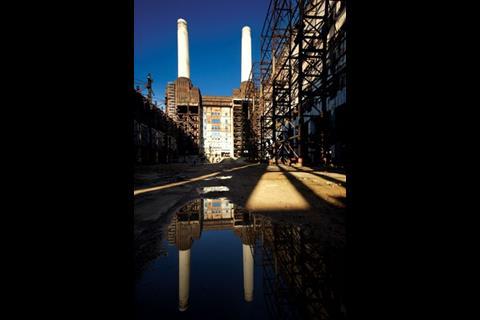

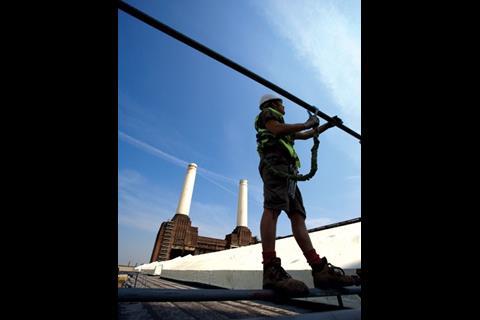

If new Battersea Power Station hopeful Treasury Holdings feels the need for a reality check on its grandiose development plan for the site, itâs not difficult. All any of the staff has to do is scale the side of the huge brick structure to a platform at the base of one of its four massive chimneys, where you get a fantastic birdâs eye view of the whole site and London beyond. Away from the building, things look rosy enough; to the east, west and south there are large expanses of empty space, punctuated only by weeds and grass, which are ripe for developing Treasury Holdingsâ ambitious Rafael Viñoly-designed scheme (see box, below).

But the closer you to this vantage point you look, the worse things get. You look straight down into the huge, roofless boiler house below, and see how badly corrosion has eaten away at parts of the buildingâs steel frame. The days of rock concerts inside this massive space are long gone; a 30m exclusion zone has been placed around each of the four big chimneys because of the risk of bits falling off and injuring people below. Standing next to the base of the chimneys, itâs obvious why. The concrete is riddled with cracks and the rebar has corroded to the point that the only option is to demolish and rebuild the chimneys. The turbine halls and annexes on either side of the boiler room still feature roofs with central glazing but glass is falling into the space below.

Tackling these not inconsiderable problems is Treasuryâs first job. The initial phase of its scheme is centred on the existing power station, so renovating the building is a priority. Even more pressing is making the structure safe. âAccess was incredibly restricted when we first bought the site â almost the whole thing was an exclusion zone,â says Rebecca Beveridge, Treasury Holdingsâ assistant development manager. Because of this, Treasury is spending ÂŁ2m on making the building safe and preventing further crumbling while the new proposals wait for planning permission. âItâs a combination of stopping the deterioration of the building and opening it up to give us access,â says Beveridge. âIt demonstrates our commitment by putting our money where our mouth is,â she adds, obviously mindful of the history of lack of action by previous Battersea developers.

So what does Treasury Holdings need to do to restore the building to its former glory?

The power station has barely been touched for 25 years. The first developer, John Broome, actually damaged the building by removing its roof, and the last developer, Parkview, made almost no impact. âParkview attempted to clean a few drains and put up netting to keep the pigeons out, but that was as far as it went,â says Jim Solomon, Buro Happoldâs conservation engineer on the scheme. He adds that Treasury Holdings is âdoing a far more comprehensive jobâ.

The mortar is one of the hardest mixes I have ever come across, a specific type of sharp sand and white cement. You canât salvage anything from it

Bob Davies, Szerelmey

Solomon says there are two key areas that need tackling to bring the building back to a useable state. The first is the fabric of the chimneys. Solomon says there are significant levels of chlorides in the concrete. âWe suspect they used river water to mix the concrete, which is of course saline,â he says. There are also high levels of carbonation â both these problems lead to corrosion of the steel reinforcement, which causes spalling and cracking.

One solution to the problem is cathodic protection. This is an electrochemical process in which another metal corrodes sacrificially rather than the original steel. However, for this to work, an electrical current needs to pass through the concrete and cracks in the chimneys prevent this. Solomon says the chimneys could be patched up, but this would only last a few years. âYou would end up replacing the chimneys before the project was finished, which doesnât make any sense whatsoever,â he says. In the long term, the chimneys simply canât be saved.

The second big issue is the interface between the buildingâs steel frame and the brickwork. Battersea Power Station may be Europeâs largest brick building, but those massive walls are only 225mm thick and are supported by a steel frame which in many places is embedded in the brickwork. âThe steelwork is corroding as itâs encapsulated in the brickwork, which has got very wet over the years. The brickwork is cracking because the steel is expanding and forcing the brickwork apart,â says Solomon.

Dealing with all this is going to cost about ÂŁ150m. One of the first jobs will be to demolish the chimneys and rebuild these exactly as the originals, using insitu concrete. This means the 30m exclusion zone can be removed. The chimneys do not go down to the ground, but are supported by a steel frame that will also need strengthening. This area was known as the wash tower, a feature of the old power station, where water was sprinkled on the coal smoke to wash out the sulphur. Unfortunately, this creates a dilute sulphuric acid, which has corroded the steel. Rather than replacing the steel, a 300mm thick concrete liner will be built to take the weight of the chimneys.

According to Solomon, the chimney replacement and wash tower strengthening work will probably hoover up half the ÂŁ150m budget. Much of the remaining money will be spent on the brickwork and steelwork. The lack of the main boiler house roof and leaks in the roofs elsewhere have caused the steel frame to rust, particularly the parapet support beams. These will need replacing and the brickwork will have to be repaired. The building has cracked near its corners because of the lack of movement joints; again, this will need repairing. Cathodic protection will be used to prevent any further damage to the steel frame.

The peregrines are a schedule one bird and we will have to accommodate them. Itâs a merry dance.

Rebecca Beveridge, Treasury Holdings

Locally based contractor and restoration specialist Szerelmey has already started work on stopping the structure deteriorating any further. Central to this is stopping any more water from getting into the building. The first job was to fix the guttering. âThe rainwater pipes were broken and smashed up but now they are repaired and clean so water goes through them to the ground rather than through the building,â explains Bob Davies, Szerelmeyâs contracts manager for the job.

Szerelmey has carried out temporary repairs to the flat roofs on either side of the boiler house, which involved patching up the existing roofs and in some cases re-covering them with asphalt. It has also taken out the glass from the rooflights and removed asbestos sheeting. To make them watertight, the rooflights have been covered with a plastic sheeting called EnviroWrap. When the building is restored, the roofs will be renewed.

The brickwork is being repaired where it is still dangerous, which involves replacing it in some places and stitching it together in others. Again, much of this will have to be redone; for example, the parapet beams will have to be taken out and the parapet rebuilt later on. âWe are limited in what we can do as we are working off cradles. Also, some of the steel has to come out so thereâs no point in doing permanent repairs,â says Davies. New bricks have been specially made for the repairs as the originals canât be salvaged because the mortar is so strong. Davies says: âIt is one of the hardest mixes I have ever come across, a specific type of sharp sand and white cement. You canât salvage anything from it.â The river wall also needs attention where barges have damaged the brickwork; this work is further complicated by having to be done at low tide.

In its years of disuse, the empty site has attracted a lot of wildlife, including a pair of peregrine falcons, which has delayed the job for two months. âWork had to be suspended and the area sealed off because peregrine falcons were attempting to nest at the top of the boiler hall wall,â says Davies. Work finally started again three weeks ago as the peregrines didnât successfully breed. Treasury Holdings has put up a temporary tower near the river in an attempt to persuade the peregrines to nest there instead, as otherwise they could cause more delays to the project. âThey are a schedule one bird and we will have to accommodate them,â says Beveridge. âItâs a merry dance.â She could be describing the past 25 years. The real test for Treasury Holdings now is getting planning permission for the scheme, raising money and consigning the dismal view from the base of the derelict chimney to history. Thatâs really quite a challenge.

A brief history of Battersea

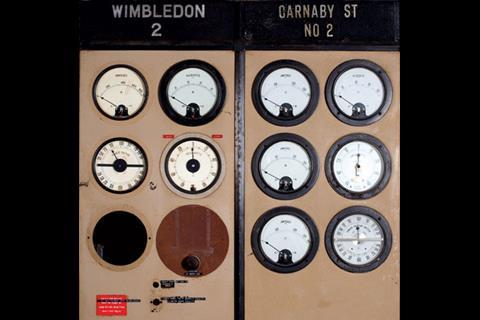

Battersea Power Station was built by the London Power Company to replace an ad hoc arrangement of numerous small stations supplying power to industries, with any spare sold to the public. It was designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott â who also designed Bankside Power Station and the red telephone box â and built in two halves. The A station was completed in 1933 and consisted of one side of the boiler house, two chimneys, the turbine hall and transformer and switch rooms. The B station was completed 20 years later, and mirrored the A station to give the building its distinctive symmetrical appearance that has proved so popular.

Power generation ceased in the A station in 1975, and with the end of Batterseaâs power generating life in sight a campaign was launched to preserve it, culminating in its grade II listing. All generation stopped at Battersea in 1983 and the electricity board held a competition to find an alternative use for the site and power station.

This was won by John Broome, of Alton Towers theme park fame. He proposed to turn the building into an US-style theme park, an plan backed by the then prime minister Margaret Thatcher. Broome bought the site in 1987 for ÂŁ1.5m and started work by removing the boiler house roof, asbestos and generating plant.

With costs escalating Broome soon ran out of cash and work stopped in 1989. He cobbled together another plan which included offices, a hotel and retail, but without money the plan languished.

In 1993 Hong Kong developer Parkview International bought the site for ÂŁ10m. It submitted a plan for a ÂŁ500m leisure and entertainment complex which it revised in 2000 to include offices, residential and more retail space. Over the next 13 years the plans were continually revised, but virtually nothing happened onsite. In 2006 Parkview sold the site to current owner Treasury Holdings for ÂŁ400m.

Can treasury succeed?

Treasury Holdings is Irelandâs largest property developer, indeed one of the largest privately owned property developers in Europe. It has 60 developments on the go and a portfolio worth âŹ3.7bn (ÂŁ2.9). One of its most high-profile schemes is eco-city Dongtan in China. Back in Dublin it has a multitude of schemes on its books including mixed-use town centre developments, shopping centres and offices. It certainly seems to have the clout to redevelop Battersea.

But can it do it? The first big challenge is transport links â Treasury Holdings has said a new tube station is crucial to the success of the Battersea scheme because of its isolation, and the fact only a tube link can handle the potential passenger numbers generated by the development. Because this is going to cost some ÂŁ350m, Treasury is hoping it can get its neighbours to help raise the money. Next door to Battersea is New Covent Garden, which plans to sell one of its two sites for development, the Post Office and developer Ballymore.

The other big challenge is the ÂŁ4bn needed for the development. Treasury say it doesnât have the money yet; instead it will focus on getting planning permission for the development over the next 2-3 years, then raise the money. It is hoping the worst effects of the credit crunch will have worn off by then, institutions will be willing to lend, and people will be prepared to snap up the properties as they are completed up to 2020.

Given the current state of the market and the failure of the two previous developers to actually build anything come boom or bust, it is hard not to be sceptical about the schemeâs prospects. And those who hate the Rafael Viñoly masterplan will be praying it shares the fate of the schemes that have gone before it.

The new ÂŁ4bn scheme: homes, offices, retail â and a 300m-high chimney

Treasury Holdingsâ proposals are the latest in a long line of very ambitious, some would say over the top, schemes for the site. The current Rafael

Viñoly-designed plan is the biggest yet, weighing in at £4bn for 750,000m2 of residential, office and retail space, with the controversial element of a giant 300m-high translucent chimney that will tower over the power station.

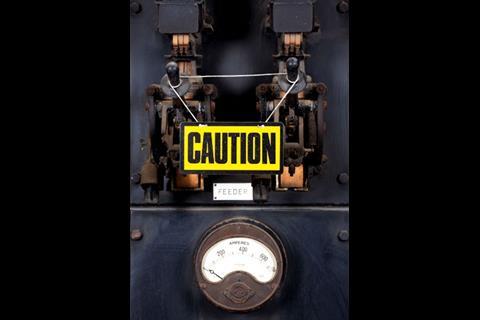

The first phase includes spending ÂŁ150m repairing the power station and transforming it into a hotel, apartments and retail premises. The boiler house will remain open to the elements and will contain apartments and a hotel facing onto an open, public space. The turbine halls to either side will also be open to the public and will include retail and leisure facilities. Treasury Holdings also wants to hark back to the buildingâs original function with an energy centre housing a combined heat and power plant running on biofuel and waste, and using two of the buildingâs chimneys as flues. The original art deco control room, the perfectly preserved jewel in the crown of the power station, will become an energy museum.

So far so good. The really controversial bit is the office space which will sit under 45,000m2 of ETFE roof supported by a cable net structure. This is shaped to funnel air up the 300m-high, 32m-wide chimney. The idea is for the warm air rising up the chimney to pull cool air from outside into the atrium of the offices inside the roof, through the office floors and out under the ETFE roof. Treasury Holdings says this will save energy demand to the tune of 67% because the offices wonât need air conditioning.

Does the chimney need to be quite so big? Treasury Holdings says that if the chimney was any smaller it wouldnât work properly, so the plan is to construct the top 60m from a translucent material to minimise its impact. But the plan to encircle the chimney with apartments below this doesnât exactly help. Treasury Holdings says the plan has been well received by all the bodies it has consulted with, including English Heritage. But it has been panned by the architectural community for overpowering the centrepiece of the scheme, the power station. For its part, Treasury Holdings points to the approval of the nearby 180m high Broadway Malyan-designed tower at Vauxhall for developer St George, which was criticised for its design quality.

Whether this scheme will get planning permission is impossible to say. The downfall of previous schemes hasnât been in getting planning, but funding. However, this is the most visually audacious scheme yet and a new, anti-tall building London mayor may mean the chimney gets the chop.

Downloads

Proposed development

Other, Size 0 kb

Postscript

For videos of Battersea Power Station and Viñoly talking about his design go to www.building.co.uk/buildingtv

Original print headline 'Battersea: the story continues'

3 Readers' comments