If a judge wants a specific document prior to trial that one party has never heard of, you’d expect someone to ask for clarification. Not in this, unnecessarily expensive, case

The costs of coming to court are embarrassing. T’was ever thus. Rare though to get a judgment published about a construction case which talks about the costs consequences, when mere procedures well before trial become ragged. Frightening costs began to run.

Let me tell you the story. Lansdowne House (St George’s Hill) is the current owner of a large house in Surrey. Seemingly the previous owner carried out extensive repair and refurb works. Lansdowne says the work done was bad. It has the benefit of one of these defects insurance schemes. Premier Guarantee runs the one here. Its website tells us that it is the market leader of structural warranties. Since 1997 it has arranged over £30bn of cover across the UK, Ireland and Spain. The scheme covers ingress of water caused by defects in the waterproof envelope for five years and major structural damage to the building for 10. Lansdowne has felt obliged to sue both Premier and the structural engineer Williamson Partnership.

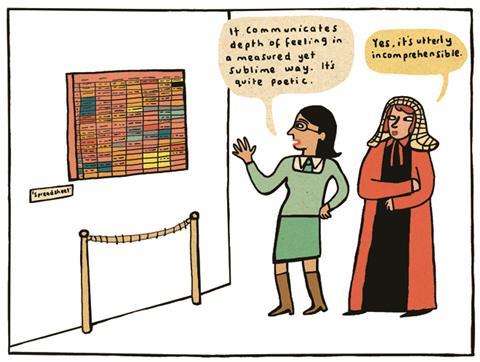

Lansdowne served up a very impressive spreadsheet, which it probably was very proud of. Useless for litigation, though

The court action got under way last year. At the case management conference the judge ordered Lansdowne to prepare and serve a document known as a Scott Schedule. Easy really. It simply sets out line-by-line the defects alleged, and item-by-item monies claimed against Premier and against the structural engineer. Lansdowne served up a very impressive spreadsheet, which it probably was very proud of. Useless for litigation, though. It cross-linked principle sums with more detailed breakdowns.

But the court wanted a simple money figure against the defect. And then there were global costs for scaffolding. Claims overlapped with other claims. Premier’s lawyers speak the language of litigation and this fancy spreadsheet flummoxed them.

The two defendants complained and got nowhere; so they complained some more, this time to the judge. Are you beginning to hear the lawyer’s money meters running? Writing letters and coming to court and all the preparation time has to be paid for by their clients. Then their clients complain that these bills wouldn’t arise at all if the other party had done what it was told. So, there we are all three parties, no doubt by now with solicitors and barristers in what I call a satellite argument, not at all about the defects, instead all about how to manage the rigmarole to eventually decide about the defects.

The judge ordered Lansdowne to go away and have another go. He also coaxed them to get a quantity surveyor on board. He set a date for everyone to come back to him to scrutinise the second effort.

Those wasted costs came to a total of £58,000 and £40,000. All this money in fees has absolutely nothing to do with the defects in a trial

And when everyone came back to court, it still wasn’t what he ordered to be done. So the two defendants are now calling for an order for their wasted legal costs to be paid out by the claimant. Those wasted costs for the first defendant came to a total of £58,000. For the second defendant it was £40,000.

All this money in fees has absolutely nothing to do with arguing the issues about defects in a trial. The case is nowhere near ready for trial. These are costs to do with procedure - the court, the legal system in the preparation period, the time when the claimant is still explaining its case to the two defendants. No, these are the actual attributable lawyer fees arising out of the toing and froing because the claimant didn’t obey the judge’s order.

Nor was the judge being awkward. All he was asking for is something he has seen numerous times: a Scott Schedule.

I suppose it made sense to the claimant to do this sort of task in house. Seemingly, Lansdowne’s finance director compiled the spreadsheet, and he relied on the information provided by the contractors who carried out the works. The judge also hinted that the court had taken for granted that Lansdowne knew what a Scott Schedule is. It’s rather like those of us in construction using jargon; we use short cuts in communicating. Dangerous.

If it is that Lansdowne was rowing its own litigation boat, and doing so to save fees, it can’t do so at the expense of the opponent. Judges can only go so far with a helping hand. Time is money.

No comments yet