HereÔÇÖs a court case of an adjudication that went to enforcement, in which all four arguments a party used in its defence were defeated ÔÇŽ

The drainage works at Smiths Dock in North Shields was a fair size subcontract. Volker Stevin, the major international civil engineering main contractor, engaged Holystone Contracts, the long-established road and sewer contractor, under the NEC3 subcontract. Four months into the drain laying Volker terminated the subcontract, much to HolystoneÔÇÖs dismay. It called for an adjudicator who decided, no doubt creating more dismay to Holystone, that Volker was right to terminate. Adjudicator two now came along at VolkerÔÇÖs request to decide the level of loss because Holystone said VolkerÔÇÖs calculation under NEC3 for compensation was too high. In the event he said ┬ú561,993 should be paid by Holystone. But the firm baulked. The parties came to the High Court on enforcement.

The idea of adjudication is to do broad justice within a tight timetable. If a load of new stuff keeps on being hurled at the adjudicator, even broad justice goes out the window

The case is interesting because it is ordinary. ItÔÇÖs what goes on in adjudication and what happens if you come to court to torpedo the adjudicatorÔÇÖs decision. Holystone complained on four points: the adjudicator allowed in new material; the adjudicator allowed the referring party to change its case half way through the process; the referring party wrongly made the adjudicator aware of a ÔÇťwithout prejudiceÔÇŁ settlement offer; if the court makes Holystone pay up, it would have a crippling financial effect on Holystone.

So, whatÔÇÖs the problem with new material coming in part way through the adjudication? Fairness, thatÔÇÖs what. The whole idea of adjudication is to do broad justice between the parties within a tight timetable. And if a load of new stuff keeps on being hurled at the adjudicator, and he is running out of time, even broad justice goes out the window. It wouldnÔÇÖt surprise me if Holystone felt under pressure in trying to find answers. The duty on the adjudicator is to do his best to see that the process is fair. In this context, fairness means ensuring enough time to comment on the new material or questions put by the adjudicator. Holystone didnÔÇÖt complain at the time so, said the judge, it canÔÇÖt complain now.

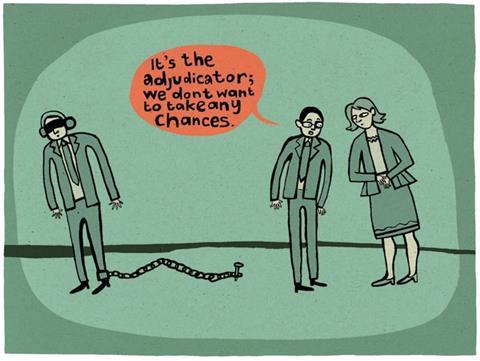

ÔÇťItÔÇÖs the adjudicator; we donÔÇÖt want to take any chancesÔÇŁ

Point two was that VolkerÔÇÖs claim for ┬ú667,000 was changed mid-adjudication to a different figure. The judge recognised that such changes are inevitable once argument begins to flow to and fro. So nobody can complain. I dare say that changes of this type are a matter of degree. If a change drives the other party to begin an inquiry with the building team it could cause yet more panic and soak up time. Meanwhile, the adjudicator has to sit on his hands. The judge said Holystone had no real complaint here.

Point three happens in adjudications periodically. Prior to the second adjudication, there had been meetings between Volker and Holystone to attempt to reach a compromise. Those meetings were ÔÇťwithout prejudiceÔÇŁ. This means that what is said in these events is not to reach the eyes or ears of the adjudicator. He is to come to the arguments afresh. In this adjudication, Holystone included in its documents information about the private meetings. It was a mistake to put this in front of the adjudicator. He was asked to resign, since he may be influenced by the offers of money to settle. It was argued that the test for bias was satisfied. Put simply, it asks if these circumstances would lead a fair-minded observer to conclude that there is a real possibility or danger that the adjudicator would favour or disfavour a party. The adjudicator dealt with the problem well. He reassured the parties that none of his decisions had been influenced by the letters. In any case, offers come as no surprise to anyone, especially since adjudication number one had decided liability and adjudication, two was about the money consequences only. So Holystone could not complain of bias.

If change drives the other party to begin an inquiry with the building team it could easily cause yet more panic and soak up time

As to the contention that enforcing the payment would push Holystone into liquidation, a plea of poverty is irrelevant to enforcing an adjudicatorÔÇÖs decision. Mind you, it might have impressed the court if Holystone had by now started an arbitration on the question in adjudication number one, whether Volker was entitled to terminate the subcontract. An arbitrator worth his salt could decide that in 28 days flat. Who knows, it might reverse the adjudication. And who knows what that would do to the amount awarded by the second adjudicator.

Tony Bingham is a barrister and arbitrator at 3 Paper ║├╔ź¤╚╔˙TVs Temple

No comments yet