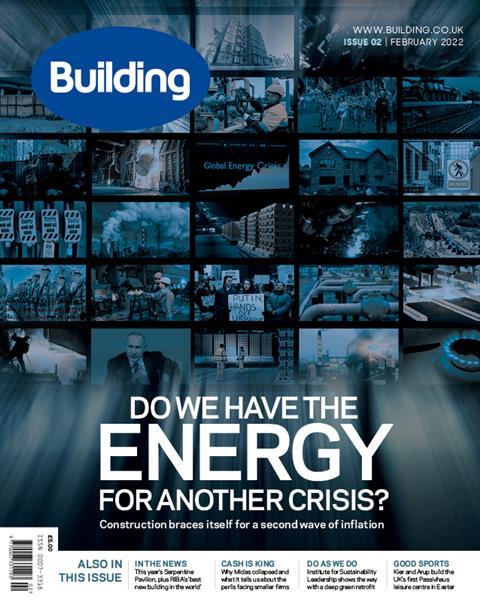

Impact on businesses is not yet part of the public debate – but it should be

Petrol prices hit 148p a litre over the weekend, a new record mostly driven by the cost of wholesale energy shooting up in response to the build-up of Russian troops on the Ukraine border. At the time of writing, diplomats warned a Russian bombardment “could happen at any time”.

But even before this threat became so real, media headlines focused on how spiralling energy costs would create a cost of living crisis for millions of UK households. Earlier this month the chancellor announced a £350 rebate (£200 of it a loan) to help people pay their bills ahead of the energy price cap rising in April.

While it seems we are all hyper-aware of feeling the pinch in our pockets, the impact of higher energy costs on businesses is not really part of the public debate at the moment. It should be.

In the construction sector the sharp end is where construction products such as bricks, steel, concrete, ceramics and aluminium are manufactured. According to UK Steel, electricity and gas costs for steel manufacturers in the UK have quadrupled over the past year.

And the pain is then passed on through the supply chain as prices jump – for example, fabricated steel rose nearly 60% in the 12 months to the end of last year. Forterra, the brick manufacturer, says prices will have to go up by about 10%.

This acute pressure from input costs is not comfortable for any firm, whatever the size

Not everyone is equally affected, however. Large contractors and housebuilders often have long-term supply arrangements and through bulk buying can avoid some of the extreme price peaks. Smaller firms do not have that buying power, and arguably are more exposed to the domestic build market which faces a lot of belt-tightening as household budgets are squeezed. But this acute pressure from input costs is not comfortable for any firm, whatever the size.

And do not forget that this is all happening at the same time as volume housebuilders and certain product manufacturers face additional regulatory costs as Michael Gove, secretary of state for levelling up, housing and communities, looks to legislate to make good on his commitment to force industry to pay for building safety remediation costs. While no one thinks leaseholders should foot the bill, some housebuilders would argue that if costs fall disproportionately on to one section of the industry, it could put government housebuilding targets at risk.

But back to the energy crisis. Energy-intensive industries in the UK say they face higher energy costs than in Europe because of carbon pricing methods and less government subsidy for firms’ decarbonising commitments. UK Steel says the price of electricity in the UK is 61% more than in France and 51% more than in Germany.

The Energy Intensive Users Group has led on this argument, criticising the government’s lack of action over rapidly rising carbon pricing. It says the rate of these rises should have triggered an intervention. On top of that, the group thinks that other government measures designed to bring relief to businesses are inadequate.

For its part, the government says it is working with industry to mitigate the impact of high energy prices, and a spokesperson even added in a comment to ∫√…´œ»…˙TV that it sees no sign construction product costs will delay building projects.

That attitude may surprise many readers, who face the incredibly hard challenge of delivering construction jobs that were priced before recent hikes in the cost of labour and materials.

> Also read: Is construction ready for a full-blown energy costs crisis?

But it is not just the risk of more delayed projects that is at stake. The collapse this month of Midas, a near ¬£300m-turnover regional contractor, points to how perilous life already is for many building firms that have been severely weakened by the disruption of the pandemic. One corporate recovery specialist told ∫√…´œ»…˙TV he expects insolvencies to keep rising throughout Q2 and Q3 this year.

Of course, insolvencies in construction are nothing new, but what might play more on ministers’ minds is the risk to key parts of their agenda if energy costs really do start to slow down the industry’s ability to deliver.

Take two central planks of this administration’s mission: levelling up and net zero. The Energy Intensive Users Group’s most forceful argument could well be that its members are the ones leading the way in the creation of essential green jobs in the north of England and elsewhere. British manufacturers are putting the case very strongly that, along with providing well-paid jobs in red wall areas, they have also taken on the net zero challenge. If they are forced to reduce their capacity, then they say construction projects may end up importing products with less sustainable credentials.

In the political realm, there are voices questioning whether the UK can now afford to pursue its net zero ambitions, which the government set out so clearly at COP26 in Glasgow last year. Construction firms, which stand to gain so much from investment in the green economy, should be putting forward the counter argument: net zero is about job creation and to some extent energy security. That message needs to come across loud and clear. As the saying goes, never waste a good (energy) crisis.

Chlo√´ McCulloch is the editor of ∫√…´œ»…˙TV