MPs have slammed them but Energy Performance Certificates could be a powerful tool in tackling climate change, says Martyn Reed

MPs are the latest group to have a moan about Energy Performance Certificates. The , all of whom pointed out that the calculation of Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs) is based on standardised data and presented in a way that gives emphasis only to an estimate of how much a home might cost to run. The main criticism is always that EPCs do not provide information on the actual, real-life energy usage and performance of the buildings to which they are attached.

Thatâs all true. EPCs were designed primarily as a cost-based asset rating, and while they actually generate more insights than most people realise, at first glance they do look like a blunt tool in todayâs policy context.

But there are also many misunderstandings about the EPC methodology. For example, the EPC uses terms like âassumedâ or âdefaultedâ, when what it really means is that an authorised figure is being used that reflects the fabric built at the time according to building regulations. Using the correct values is the only way to undertake effective energy assessments of existing dwellings. The words therefore are unhelpful and mean that many people think it is not accurate, which is untrue.

Taking our cue from food labelling, we already have a clear idea of how we could present key performance data for a property in a visually engaging way

Despite the issues with EPCs, they should be retained. Itâs too easy to underestimate just how important they have been over almost 15 years of use, especially in terms of identifying households at risk of fuel poverty and in the setting of benchmarks for energy efficiency improvements.

Thanks to EPCs â widely recognised as a world-leading system â the UK, its homeowners, landlords, tenants and policy-makers now have access to a vital data record of more than 20 million homes and non-domestic buildings. That mass of information is incredibly important as we try to tackle energy inefficiency on a grand scale.

> Also read: How EPC requirements could leave buildings at stranding risk

So in an era of fast-developing insights and powerful intelligence through the linking and analysis of data sources, what needs to happen next to take EPCs to the next level?

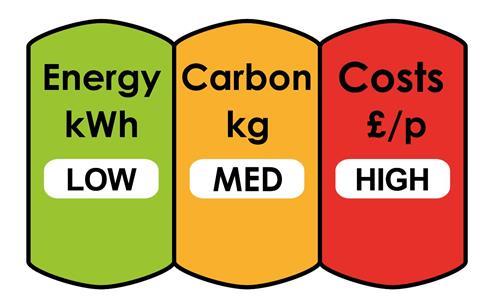

First, we must redesign the label itself to reflect the full extent of information we have gathered. The proposal from the EAC mirrors exactly what Elmhurst has suggested: we need to redesign the certificate so that it shows cost (ÂŁ), carbon (CO2) and energy (kWh). Legislation can then refer to the metric that it is intending to improve â for example, fuel poverty legislation could continue to be based on tracking the cost metric, and climate change policies could focus on targets using the carbon metric.

Taking our cue from food labelling, we already have a clear idea of how we could present key performance data for a property in a visually engaging way, and giving equal prominence to carbon emissions, energy demand, running costs and fabric efficiency.

Second, to address the accuracy and performance gap issue, the routine measurement of actual energy performance should be combined with updated EPCs using the newest version of the Standard Assessment Procedure (SAP). The government is already consulting on this for the largest 7% of industrial buildings, but this easily could be done for smaller buildings and homes through the use of low cost SmartHTC technology too.

Finally, trigger points for the commissioning of EPCs must also be increased. We estimate that there are about 14 million properties in the UK without an EPC as they have never been sold or rented out in at least the last 10 years. By increasing trigger points and reducing their expiry date to three years, we can ensure EPCs feed more up-to-date information into the database for benchmarking the roadmap to net zero, and that they enable better-informed decision making for home improvements.

EPCs are not without their problems. But theyâre also not redundant and we shouldnât look to a replacement system so easily. By leveraging the information contained within them, redesigning them to make them more useful to government and user friendly for homeowners, and tweaking the policy that exists around them, we can create a really powerful tool in our fight against climate change.

Martyn Reed is managing direct of Elmhurst Energy

2 Readers' comments