Ciara Walker of Arcadis highlights the programme of investment in infrastructure and tourism-related construction driven by the Dubai City Plan 2021, exemplified by World Expo 2020

01 / Introduction

In the last two decades, Dubai has cemented its place as a leading international city, in particular as a bridging point between East and West. The city is an icon of trade, tourism and connectivity, exploiting the opportunity of having two-thirds of the world’s population within an eight-hour plane journey. Sustained development in the built environment has given Dubai many of the world’s largest and most innovative buildings, including the Burj Khalifa, and booming commercial, hospitality and leisure sectors.

Dubai is now focused on maintaining a path of sustainable development. The Dubai City Plan 2021, launched in 2014, includes objectives for Dubai to become the capital of the economy of the Islamic world, to become a smart city, and to continue the diversification of the economy. With global trade picking up, Dubai is well set to continue to develop in the run up to the World Expo 2020 and beyond.

Table 1: City indicators

| City-region indicator | Data |

|---|---|

| GDP (2016) | £80���� |

| Year-on-year economic growth (2016) | 2.70% |

| Population (2017) | 2.7m |

| Population growth rate (annual) (2016) | 4.9% |

| Overnight stays (2016) | 14.2m |

02 / Economic and political overview

Economics

Dubai is a bright spot in a region which has recently been affected by lower oil prices. Oil and gas provides no more than 5% of GDP, and Dubai has focused on diversifying its economy for many years. This has helped to cushion the impact that a lower oil price has had on other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) markets.

An important feature of this diversification is Dubai’s free economic zones. Jebel Ali Free Zone for example is the world’s largest free trade area, hosting 7,000 businesses, supporting 144,000 jobs and driving 50% of Dubai’s exports by value. With a recovery in the price of oil and a wider pick-up in the global economy, increased tourism and trade will provide a further boost to Dubai’s growth.

Dubai’s biggest revenue generators are trade, which accounts for 27% of GDP, manufacturing, financial services and transport. Tourism, real estate and construction also play an important role in Dubai’s outward looking and diversified economy. For example, Dubai is ranked the fourth most visited city in Mastercard’s Global Destination Cities Index.

Dubai’s population is also booming and is anticipated to grow at around 5% per annum to 3.1 million by 2020. Dubai is forecasting 3.1% GDP growth in 2017, a steady increase compared with 2016’s 2.7% growth.

Politics

Dubai is part of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), a federation of seven emirates. Dubai is a monarchy that is partially governed by the Federal Supreme Council of the UAE. The pace of local government reform is set primarily by the Emir of Dubai, Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid al Maktoum, who launched the Dubai 2021 vision. Dubai is considered one of the most advanced emirates in terms of reform, with huge investment over recent years to diversify the economy with a focus on tourism, retail and real estate. Politics and economics are closely intertwined in Dubai and the royal family is associated with many major Dubai-based enterprises.

03 / Innovation and Sustainability

Dubai Plan 2021

The Dubai Plan 2021, developed by the government of Dubai, covers the period of 2016 to 2021. Its mission is to “plan, develop and manage an excellent city that provides the essence of success and sustainable living”. Key elements of the plan include the launch of an initiative to transform Dubai into a capital of the economy of the Islamic world, a smart city strategy and an industrial strategy. Dubai’s success in securing World Expo in 2020 is an important part of the strategy but by no means is the only area of development focus.

The plan covers six main areas including:

- People Equipping people to contribute to the continuing development of Dubai

- Society ��ɫ����TV a cohesive, sustainable and inclusive multicultural society

- Experience Making Dubai the preferred place to live, work and visit

- Government Focused on meeting the needs of society in an efficient and transparent manner

- Economy Aiming to be a top five global centre for trade, logistics, tourism and finance

- Place A smart and sustainable city with a fully connected and integrated infrastructure.

Evidence of this long-term thinking includes investment in additional attractions such as theme parks to sustain growth in tourism post-Expo.

Similarly, a significant volume of planned infrastructure investment will also go a long way to ensuring growth is sustainable and that the needs of the rapidly growing population continue to be met.

Innovation

Dubai prides itself on being innovative and experimental. Recent tests of drone taxis, and other smart city investments, emphasise that Dubai is always looking and preparing for the next big thing. This is exemplified by a recent deal to evaluate the potential of Hyperloop, an ultra-high speed mass transit system that could potentially reduce travel times for the 65 miles between Dubai and Abu Dhabi to 12 minutes.

Focused on other aspects of innovation, the Dubai Roads and Transport Authority (RTA) has recently announced a five-year roadmap preparing the ground for autonomous transport, aiming for 25% of all trips to be autonomous by 2030. This plan envisages the implementation of 34 projects ranging from autonomous drones to self-driving buses and taxis. Dubai aims to be ready for future technologies by developing safety standards and introducing relevant legislation (for instance, for driverless cars) as well as building the required infrastructure.

Sustainability

Dubai aims to become one of the world’s top 10 most sustainable cities by 2020, taking a myriad of actions to achieve this goal, including implementing green building rules (with a target for the rehabilitation of 30,000 buildings), and investing in renewable energy, including the world’s largest solar park. With a goal to reduce energy and water demand by 30% by 2030, the government has so far helped to conserve 1,344GW of electricity, 5.6 billion gallons of water and 714,000 tonnes of carbon emissions.

04 / Infrastructure

Dubai is investing across many infrastructure sectors, with the most investment in rail and road infrastructure. Dubai will continue to leverage its geographical advantage as a transit point between East and West with massive investment in airport infrastructure. The mega airport expansion under way at Al Maktoum International Airport has been named as one of the world’s five largest infrastructure developments by Knight Frank.

The airport is designed to complement existing facilities, and once complete, will have the capacity to handle 16 million tonnes of freight and 220m passengers per year. The existing Dubai International Airport overtook London Heathrow as the world’s busiest airport in 2015, and handled 84 million passengers in 2016.

With the population of Dubai set to double by 2030, further investment in Dubai’s public transportation infrastructure is necessary to keep up with the forecast growth rate. The Dubai Plan 2021 sets targets for transport improvements, including reducing average travel time in peak hours from 1.89 hours in 2016, to 1.55 hours, and growing the share of journeys taken using public transportation from 14% to 19.6% by 2021. In June 2016, the RTA awarded a much-awaited extension to the Dubai Metro Red Line. This £2.2bn extension will serve the Expo 2020 site. Work on the 15km long extension started in 2016, with operation commencing in May 2020.

Congestion remains a challenge in some parts of the city. This is partly managed with toll roads, whose prices have recently been increased. There is also significant ongoing investment aimed at improving the road system, including regular road maintenance, the Shindagha Crossing Bridge, and RTA’s five-year plan to pave internal roads for 16 residential districts in Dubai.

In addition to core public transport investments, Dubai is also investing in:

- Waste infrastructure, including the £2.6bn Dubai Strategic Sewerage project, commencing in July 2017, aiming to modernise the sewerage system and to expand capacity

- Power infrastructure, including a 800MW phase of the Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum Solar Park, which will be the world’s largest single site solar power generator, with a planned capacity of 5,000MW by 2030, involving a total investment of £10.5bn

- Water infrastructure, including the massive project to extend the Dubai Canal, joining it back to the sea, providing additional space for mixed use waterfront development, as well as creating the opportunity for water taxis.

Table 2: infrastructure projects pipeline

| Aviation | Consolidated infrastructure packages | Marine | Rail | Road | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value of projects ($bn) | 4.1 | 1.7 | 4.5 | 42.7 | 10.6 |

| Number of projects | 7 | 26 | 21 | 18 | 141 |

Source: BNC Project Intelligence Database

05 / Construction and Real Estate Markets

Dubai has a large pipeline of construction projects to be delivered over an extended timescale. Dubai’s largest development, Dubailand for example, is a 25-year mixed-use programme of over 350 projects collectively worth £50bn. Dubai’s backbone of large-scale development is cyclical and the market is set to be very busy for at least the next three years in the run up to the Expo.

The increasing diversity of the construction economy, with large-scale infrastructure investments extending beyond 2020, has increased the predictability of workload. The current active pipeline of private and public projects puts the industry on course for steady growth of at least 3% in 2017, with potential for further expansion in the lead up to the Expo.

One of the challenges for the construction market could be the volume of work planned to be delivered by 2020 to coincide with World Expo 2020, and the need to attract sufficient capacity into the market. Though there is a nationality quota for construction workers, like other cities in the region, this does not limit labour supply due to the maturity of the market and wide pool of labour available to Dubai contractors. Like most Gulf Cooperation Council construction markets, not all materials are manufactured locally and some therefore need to be imported, which can be a cost driver when other regional markets are also busy. Given this limitation, there is a potential risk of inflation due to the volume of work being planned to be delivered in support of the 2021 plan. However, because of the impact of the weak oil market on demand for construction across the GCC region, Dubai has been able to deliver its programme in a less inflationary market than might have been the case.

Table 3: Selection of mega projects worth over £1bn

| Project | Status | Sector | Estimated net project value (GBP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dubailand | Construction | Mixed-use urban development | 50bn |

| Al Maktoum International Airport Phase 2 | Study | Mixed-use urban development | 14bn |

| Downtown Jebel Ali | Procurement | Mixed-use urban development | 11bn |

| Dubai Creek Harbour | Construction | Mixed-use urban development | 9bn |

| Al Jadaf Culture Village | Construction | Mixed-use urban development | 8.5bn |

| Deira Island | Construction | Mixed-use urban development | 6bn |

| Mall of the World Entertainment District | Design | Retail mall | 4.5bn |

| Dubai South Villages | Construction | Residential | 4.5bn |

| Dubai Wholesale City | Construction | Free trade zone | 3.5bn |

| Sobha Hartland Development | Construction | Mixed-use urban development | 2.5bn |

| Dubai Metro Red Line extension | Construction | Transport | 2.3bn |

| Dubai World Trade Centre | Construction | Commercial development | 1bn |

Source: MEED

06 / Residential

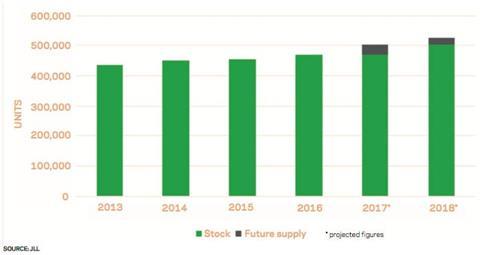

After a period where investor demand declined due to low oil prices and a challenging economic climate in Russia and China, the sales prices for both apartments and villas show signs of stabilising.

Dubai saw only a 1% decline in prices year on year for apartments, and 2% growth for villas, though transactions were down in Q4 2016.

Meanwhile, rental indices continue to fall for both apartments and villas, with an annual decline of 6% for apartments and 8% for villas in 2016.

However, despite falling asset values, the Dubai residential market outperformed most regional competitors, including Abu Dhabi.

A total of 14,600 residential units entered the Dubai market in 2016, the highest level since 2012. Strong supply is expected to continue, with 31,000 units slated for completion in 2017. Oversupply of prime housing is driving prices down.

Shifting investment from prime to affordable housing would not only provide a social benefit, it would likely alleviate downward pressure on prime prices as well.

The disconnect between the performance of the rental and sales markets is expected to continue into 2017, with the sales segment likely to see recovery first, with a slight lag for the rental market.

Figure 1: Dubai residential supply

07 / Commercial

Dubai’s economic free zones, including the Dubai International Financial Centre, have contributed to consolidating Dubai’s position as a global financial and business services hub. In addition to global banks and financial institutions, multinationals including Microsoft, Hewlett-Packard, Dell, Oracle Corporation and IBM have chosen to locate headquarters in Dubai.

Given the steady demand for office space, the Dubai office market has been more resilient in recent years than other cities in the GCC. However, there has been evidence of companies delaying expansion plans until late 2017/2018 by opting to extend existing leases in the short term.

Delivery of 129,000m2 of office accommodation in 2016 was brought to market, including notable completions such as Westbury Square, and the Butterfly ��ɫ����TV in Dubai Media City.

Average grade A rents remained stable throughout 2016, at £409/m2, while in Abu Dhabi rents fell by 5%. Occupancy rates remained strong due to steady demand and limited supply.

The performance of the commercial sector has become more polarised, and a widening gap between the primary and secondary segments is expected in 2017. With pre-leasing activities remaining buoyant, further office development is expected, and until additional high quality supply is added, upward pressure on rents can be expected.

To respond to this, approximately 300,000m2 of office space is in the pipeline for 2017, with supply shifting from the traditional central business district to other areas of the city such as Business Bay and Silicon Oasis.

Figure 2: Dubai residential supply

08 / Hospitality and leisure

Everything in Dubai is set up to make it a great place for tourism. The quality of facilities is first class, services are excellent and the government has proven very responsive to the changing leisure demands of its citizens and tourists.

The city focuses both on regional tourism aimed at the rapidly expanding Islamic market as well as its role as a high-end global getaway. Dubai is aiming to attract 20 million annual visitors by 2020, and around 25 million are expected to visit the Expo.

The importance of hospitality to the economy is illustrated by the number of hotel rooms per capita, which in Dubai is significantly higher than other tourism hubs (for instance, 27.9 keys per 1,000 population, compared to second ranked Singapore, at 10.5). Dubai’s focus on the premium segment is illustrated by the ratio for luxury rooms per capita (12.9 per 1,000, compared to next highest New York, 2.6 per 1,000).

An increase in new room supply, coupled with a strong currency changed the balance in supply and demand in 2016, which has resulted in lower room revenues. Average daily rates (ADR) decreased by 9.5% in the year to August 2016 and revenues per available room (RevPAR) fell by 6.3%.

However, hotel occupancies have remained more resilient, down by only 0.5% in the year to August 2016 despite an increase in the number of rooms.

While hotel occupancy rates have been maintained at relatively positive rates in 2016, competition will increase in 2017 as new hotels come on-stream. It is also worth noting that the budget and mid-market segments remain underserved and the performance of this segment could be very strong.

In order to sustain tourism demand after World Expo 2020, Dubai has invested in the first big theme parks in the Middle East. In September 2016, the world’s largest indoor theme park opened, the £800m 140,000m2 IMG Worlds of Adventure.

This was followed in December 2016 with the launch of the £2.7bn Dubai Parks and Resorts, comprising three internal parks totalling 2.8m m2.

The last park in this complex, the £540m Six Flags Dubai is under construction, and scheduled to open in 2019.

These parks will give Dubai another point of differentiation in the region, and further cement its position as a global tourism hub.

09 / Industrial

The UAE aims to generate 20% of GDP from industrial sectors by 2020, in a continued drive to diversify its economy away from natural resources. Dubai has been in the vanguard of this diversification strategy, aiming to make Dubai an international hub for innovation and sustainable industrial activities. Under the 2021 strategy, six industrial subsectors are being targeted: aerospace, maritime, pharmaceuticals and medical equipment, aluminium and fabricated metals, fast moving consumer goods, and machinery and equipment. The industrial sector has demonstrated solid growth and Dubai now has 18 industrial areas, eight of which are within free zones.

Many of these areas are jointly used for industrial and logistics activities, which reflects a focus on trade and logistics and demand for these facilities. Enquiries from the industrial and manufacturing sector are growing, an indicator that the industrial strategy is working. Unilever announced plans to build a £210m factory in Dubai Industrial Park to manufacture for export to 80 countries in the Middle East, North Africa and Europe.

Falling oil prices weakened investor and consumer confidence in 2016, however, and Grade A rents remained flat over the year. This is partly due to a lack of supply of quality warehousing, particularly in on-shore locations. As the quality of supply has improved, Grade B rents have fallen by 13% on average across the submarkets, largely as a result of the modernisation of industrial building standards and regulations. Rents range from £57-£113/m2 per annum depending on the quality of an industrial zone’s facilities. The relatively weak performance of the global trade market has affected the performance of the sector in the short to medium term. However, looking forward, with global trade picking up, and with the UAE’s commitment to diversifying its economy through continued investment in industry, demand is likely to improve, accelerating rental growth and demand for new space.

10 / Conclusion

While the attention of the world might be on the World Expo 2020, Dubai continues to deliver a broader based development programme aimed at ensuring the long-term diversity and sustainability of the economy. Massive investment in infrastructure, although targeted for completion in time for the Expo, is designed to enable Dubai to meet the demands of its growing population and to enable the vision of the 2021 Plan. By investing in tourism, commerce and industry, Dubai is continuing the diversification of the economy, investing in greater resilience in anticipation of a more dynamic and competitive world economy.

Preparations for a programme as critical as the Expo are inevitably becoming an increasingly significant part of the work of the construction industry - contributing to sustained growth in the sector. The industry also continues to focus on meeting the needs of other parts of the economy including commercial and residential.

Dubai is one of the safest locations in the world, and has the will to drive the changes needed to address challenges associated with its growing population and economy. Given the investment needed to underpin this future, prospects for construction in Dubai will continue to be strong over the coming years.

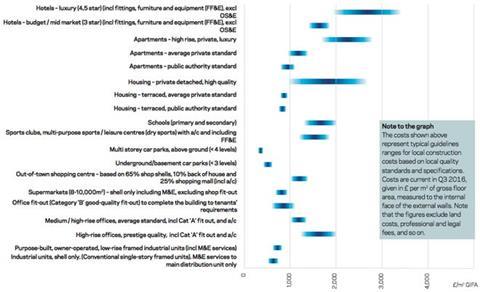

Figure 3: Indicative costs per m2 in Dubai (costs in £/m2 GifA)

No comments yet