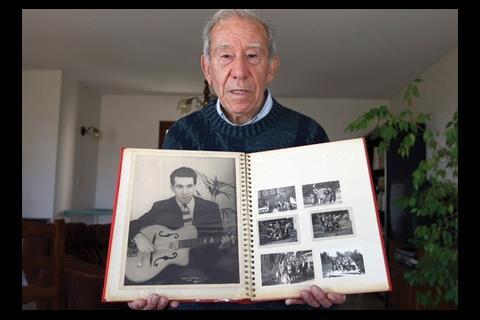

Sixty-five years after he entered Auschwitz, Albert Veissid tells Ben King the extraordinary tale of how his fictitious construction skills helped him survive

Albert Veissid is one of the few people who can say that his building skills saved his life. The irony is, he never had any.

In 1944, aged just 20, Veissid was sent from his home in Lyon in the south of France to Auschwitz, the extermination camp in Poland where more than 1 million people, mostly Jews, were murdered between 1942 and 1945. As he was standing in line waiting to have his head shaved and a prisoner number tattooed on his arm, he made a snap decision that became a matter of life or death.

ãWhen I entered Auschwitz I said I was a mason,ã says Veissid, now 84 and living in Provence. ãI actually worked selling clothes in a shop, but I remember my friend leaning over and quickly saying to me, ãItãs better that you write masonã. If you look up the camp documents you can see I am marked down as someone with construction skills.ã

Veissidãs lie about his skills meant the Nazis selected him to work in a construction unit reinforcing a large underground bunker near the camp with six Polish men.

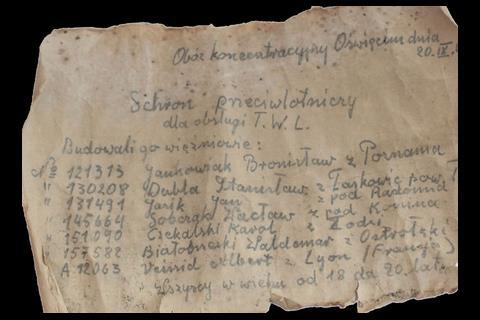

Last month, builders working at the same site dug up a bottle hidden in the concrete wall of the school that now stands there that brought Veissidãs story to the worldãs attention. The bottle contained a note with ã9 September 1944ã and the names, camp numbers and home towns of seven young prisoners aged between 18 and 20 from France and Poland written on it. The discovery has stirred up horrors that Veissid had spent years trying to forget. Indeed, he canãt even remember writing his name on the paper, though, having seen it, he is convinced he must have. ãOn that document there is my first name, surname, my camp number, as well as ãLyon, Franceã,ã he says ãIt was I who wrote that on the bottom. Itãs my handwriting.ã

He refers to the message as a ãwitness statementã penned by men who knew they might not live to tell their tales in person. Now, after years of silence, Veissid has decided to do just that and give a few select interviews about his ãinfernal existenceã in the camp and how posing as a builder kept him alive. ãThis is what you might call a scoop,ã he says. ãAfter this, I wonãt talk about it any more.ã

A means of survival

Veissidãs job in Auschwitz was to use stone blocks to reinforce a bunker which he was told would be used as an air raid shelter. Often, though, these structures were put to use as gas chambers or crematoriums. He did not know this at the time.

Veissid says manual labour was preferable to the life of a standard prisoner. ãWe were very lucky to work somewhere without the attention of kapos [inmates, mostly convicts, who worked as supervisors] and the SS, because the kapos would beat you, and the SS would beat you even more,ã he says.

A Hungarian man he was working with knew a bit more about construction than Veissid, so helped him pick up some basic skills. ãHe knew how to mix cement with water and that sort of thing; enough for us to get by,ã he says. ãI wouldnãt say he was a professional mason, but he knew enough for us to fool the kapos.ã

He also struck up a friendship with his workmates. Among them were the six Polish builders also named on the message, who smuggled him extra rations of vegetable soup, as non-Jewish Poles were given more food than deportees from abroad. ãNormally the Poles would have had nothing to do with a little Jew from Lyon,ã he says. ãIt was very difficult to survive on the rations of the deportees, but because I was working in this group with the Polish, they had more to eat. I was able to eat some of their soup and build up my strength. They helped saved my life.ã

In another stroke of luck Veissid was largely unsupervised by the guards for several weeks, so his lack of building skills went unnoticed. This also meant he was able to rest and build up his strength ã something almost unheard of for most concentration camp inmates who, if they were not executed, were likely to be worked to death.

I worked selling clothes in a shop, but my friend said, ãitãs better that you write masonã. I was marked down as someone with construction skills

But this grace period didnãt last long. When the kapos inspected his work and realised how little had been done, he was brutally punished ã something he refuses to discuss. ãI was lucky they didnãt hang me,ã he says. ãTo them, what I was doing was effectively sabotage. They did things that I canãt explain, but they spared my life. At least they spared my life.ã

Having escaped death at the hands of the kapos and guards and buoyed by the strength he had mustered resting in relative privacy in the bunker, Veissid was able to survive several more weeks until the Soviet army began its approach in January 1945.

The prisoners were moved westwards towards another camp, at Buchenwald in Germany, away from the Russians. ãIn France, we call that ãthe March of Deathã,ã says Veissid. ãIt was the middle of winter, there was deep snow and it was extremely cold. I was able to go on because I had built up my strength.ã

Rescue and recovery

Veissid was rescued by the Allies, after walking all the way to Karlovy Vary, in what is now the Czech Republic. He does not remember how long he had been walking for. He spent the next three months in a sanatorium, recovering from an attack of tuberculosis. When he had fully recovered he was able to resume his career selling clothes in Marseille and the neighbouring towns.

While he was in Auschwitz he had met an old neighbour ã a 17-year-old boy named Rafael Carraco ã who told him his close family had escaped capture. ãHe said, ãAlbert, donãt worry. Your parents headed off to hide themselves long agoã,ã says Veissid. ãI gave him a piece of bread to say thank you, because he rescued my morale, because I was relieved to know that my parents were hidden.ã It later emerged that his father had sheltered in a cinema, his mother at a farm 20km from Lyon and his brother under a bridge. They all survived the war.

ãIt was very lucky I was the only one of my family to be deported. I can name many families where the mother, father, sons, daughters, cousins were all deported ã and never came back.ã

When Veissid was repatriated to the Hotel Lutetia in Paris, he sent his family a telegram saying he was still alive. They were reunited at Lyon Perrache station in June 1945.

Looking back

Now, an elderly gentleman with children and grandchildren, Veissid is focused on living his life rather than looking back. He says that this is why he has not spoken of his time in Auschwitz for so many years, and explains how caring for his family has spared him from survivorsã guilt and helped him move on. ãThere are deportees who live their whole lives with this,ã he says.

ãI donãt have the traumas any more, because life carries on,ã he adds. And with that, Albert Veissid turns his attention back to his life in Provence after deciding, just for a few days, to tell the world the remarkable story of the clothing salesman who posed as a builder to survive Auschwitz.

Postscript

Original print headline: 'I told the SS I was a builder, and it saved my life'.

No comments yet