...when we came out of college, people used to sweep the site before we went to visitŌĆÖ

How they made it Things might not be as groovy as they were when he was designing swinging-sixties boutiques and painting houses pink with impunity, but CZWGŌĆÖs Piers Gough tells Olivia Boyd he could never imagine doing anything else

What made you want to be an architect?

When I was 16, my dad suggested it to me and it seemed like a great idea. I remember thinking modern architecture was so terrible that I couldnŌĆÖt help but do better, so I started drawing buildings whenever and wherever I could. I had a year off between school and going to the Architectural Association (AA), when I did tons of drawing in the street.

Did you enjoy your time at the AA?

I adored it. It was the height of the swinging sixties and London was an amazing place to be. There were terrific people around ŌĆō Peter Cook was the fifth-year master, in the year above me was Nick Grimshaw and just after me was Will Alsop, so I was in a sandwich of brilliance. The AA had the feeling of flying.

Who were your idols?

IŌĆÖve always liked architects beginning with ŌĆ£GŌĆØ. One of my great heroes is Bruce Goff and I like Antoni Gaud├Ł, Hector Guimard and Bertrand Goldberg, who did the Marina Towers in Chicago. Then, of course, thereŌĆÖs Frank Gehry ŌĆō probably the greatest ŌĆ£GŌĆØ of all. I think the Gs had it in the 20th century, so I was born with the right initial.

Were you very ambitious?

Oddly enough I wasnŌĆÖt. I was ambitious not to work for anyone else, which is a sort of negative ambition. I didnŌĆÖt have the kind of ambition that said I must build a major railway station before I turn 50.

How did you go about starting up?

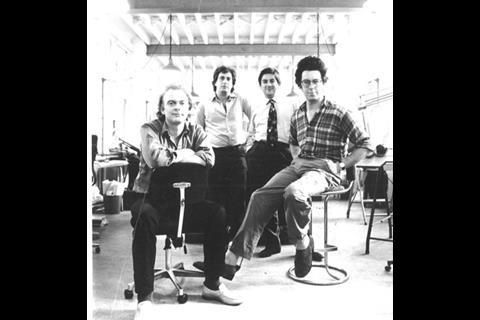

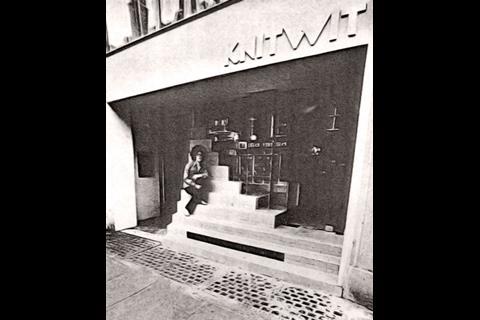

At college I teamed up with Rex Wilkinson, Nicolas Campbell and Roger Zogolovitch, who later became my partners at CZWG. We took an office in the school and even had a telephone, which in those days was quite hard to get. We did our first job while still at the AA in 1968 ŌĆō a trendy boutique in South Molton Street that sold angora wool clothes. It wasnŌĆÖt at all intimidating ŌĆō planners were nice in those days and builders were great. We even had set painters from films painting the shop. It all seemed very benign.

What were the early years like for CZWG?

It was tough. We got a nice-sized project for our first job in 1975, which was an auction house in Bayswater. We painted it pink and got quite a lot of amused press coverage ŌĆō someone described us as ŌĆ£interior decorators unwisely let loose on the outside of a houseŌĆØ. After that I guess we thought the phone would just ring, but it didnŌĆÖt really. It was quite hard work in the first years. There was a recession too, so the mid-seventies wasnŌĆÖt a great time.

Did you ever consider changing career?

No. After spending that long as a student and setting up a business, doing something else was inconceivable. Roger was thinking exactly the opposite and went off and became a property developer, but the other three of us were going to pursue this, come rain or shine.

Was there a turning point?

Things really picked up in the eighties with the Docklands. Planning there was much easier than anywhere else because it wasnŌĆÖt democratic. There were four men who sort of ruled and if they liked your building, you got to do it. That was exhilarating because you could design what you wanted rather than just what was acceptable, nice or friendly.

What was your greatest achievement?

I love the Green Bridge in Mile End. It was an idea from scratch, without a brief. I was lying in the park, looking at the sky, thinking: ŌĆ£What would be great?ŌĆØ and I came up with: ŌĆ£A bridge carrying the park over the road.ŌĆØ Persuading the Lottery to pay for it and building it was a good feeling.

What has been your toughest challenge?

The competition to design an extension to the National Gallery. That period was so screwed up by postmodernist buildings, it was bloody difficult to do postmodernism well. I was torn between what I felt the gallery wanted and what I felt I should do. Eventually, Robert Venturi won the competition ŌĆō he was the master of that sort of complexity and contradiction. That was the toughest time and one I regret the most. I had the chance to do it and I didnŌĆÖt get it right. It would be easier now IŌĆÖve been around the block a few times.

How did you persuade Frank Gehry to design a Brighton leisure centre?

Frank swears that until he was hooked on the project, the developer Josh Arghiros and I slightly forgot to mention that the King Alfred leisure centre was a competition not a straight commission ŌĆ”

Is architecture a tougher job these days?

The trouble is architects are lower down the pecking order now. You are almost seen as a subcontractor who provides drawings. When we came out of college, people used to sweep the site before we went to visit. However young, spotty and inexperienced you were, you were the architect, so you were important. You canŌĆÖt really say that anymore. Maybe it is more friendly not having a hierarchy, but I donŌĆÖt think it quite reflects what architects do. It is a stupendously difficult job.

We hear youŌĆÖre mates with Janet Street-Porter. WhatŌĆÖs she like?

Janet takes a tigerish relish in being tall, loud, unsentimental and design super-savvy. She is the scourge of the philistine establishment. And can she cook.

What do you look for in job candidates?

Enthusiasm is absolutely number one. It is so dispiriting that people can do seven years of study and not be nuts about the subject ŌĆō it is amazing how flat some people who come to talk to us are.

Give us some advice

DonŌĆÖt do things half-heartedly. Architecture is too harsh, too badly paid and too poorly respected to be lukewarm.

The story so far ŌĆ”

Piers Gough, 61

1946

Born on 24 April in Brighton

Late 1950s

Began at Uppingham School, Rutland

1971

Graduated from Architectural Association School of Architecture

1975

Co-founded Campbell, Zogolovitch, Wilkinson and Gough (now known as CZWG)

1998

Awarded CBE

2002

Awarded Royal Academician status

Postscript

For more careers advice and hundreds of jobs, go to www.building4jobs.co.uk

No comments yet