The stereotype of back-to-back housing as cramped and poorly lit is overturned by Signal Townhouses, where thoughtful design has maximised natural light and outdoor space. Ike Ijeh takes in AHMM’s new 16‑home Greenwich scheme. Photography by Tim Soar

There can be few more historically reviled building types than back-to-back housing. Even today, over a century after the 1909 Housing Act that effectively banned their construction, back-to-back housing is still synonymous with many of the social and public health ills that afflicted large swathes of 19th- and early 20th-century urban Britain.

Poor ventilation, limited daylight, cramped space, low-quality, non-existent amenity space and substandard accommodation were just some of this housing type’s drawbacks. These all helped ingrain stubborn social prejudices that negatively associated such homes with the slums and rookeries of the poor, factory-working underclass. Their location barely helped in this regard: while the East End of London had its fair share of back-to-backs, they tended to be concentrated in the industrial cities of the Midlands and the North of England.

However, back-to-backs did offer two singular advantages. They delivered relatively high densities and they were cheaper to build than traditional terraces. This is exactly why back-to-back housing has of late been making something of a quiet, tentative comeback.

Over the last decade Urban Splash has applied a modernised form of the typology to its 1,700‑unit New Islington development in Manchester. And in Newham, east London, Peter Barber Architects’ superb McGrath Road scheme from 2016 brilliantly recalibrates negative perceptions of back-to-backs by enigmatically embellishing them with sculptural arches and crafted brickwork.

The latter feature also makes a significant contribution to the latest offering among the growing contemporary inventory of innovative back-to-back reinventions. Signal Townhouses, designed by AHMM, was last month announced as one of the winners of the 2018 Housing Design Awards. The double terrace of 16 three-bed, three‑storey houses is located in south-east London, halfway between Greenwich town centre and Greenwich Peninsula.

They are also located just east of the massive Lovell’s Wharf and Enderby Wharf residential schemes being built along the Thames riverside by BPTW Partnership and Simpson Haugh respectively. The Telegraph Works site was previously owned by neighbouring French telecoms giant Alcatel-Lucent and is thereby yet another example of the long, slow de-industrialisation of the Greenwich riverside.

But of course the defining feature of Signal Townhouses is its back-to-back housing composition with, in this case, eight townhouses placed on either side of a central party-wall spine. So, why opt for back-to-back housing at this location in the first place and, more pointedly, how has it been made to work?

Why back-to-back?

For AHMM partner and co-founder Paul Monaghan, an early reason for choosing back-to-back was that it offered a neat townscape solution. “The development faces a new development of much larger seven- to 16-storey blocks of flats to the north, the Alcatel factory to the east and rows of typical London terraced streets to the south that predate 1900,” he says.

“By not aligning the new houses to the street, they assume a north-south orientation. This means that they avoid looking onto the factory or the largest flat blocks, but they instead face onto the backs of the existing terraces to the south.”

With the new houses’ vertical proportions, deep recesses and flecked buff brickwork, they are clearly inspired by the Victorian terraces that they overlook. Even the rhythmic sequence of projecting full-height bays that partially segregate the new townhouses could be viewed as a more forceful projection of the bay windows so synonymous with Victorian and Edwardian domesticity. Unlike the gross townscape incursion of the larger blocks of flats opposite, Signal Townhouses makes a handsome, restrained yet carefully contemporary contribution to the traditional residential townscape that typifies London and forms the southern boundary to the site.

Monaghan argues that had the traditional house and rear garden format of the adjacent Victorian terraces been used on this site, it would have accommodated only half the amount of units that the back-to-back approach has allowed. And this touches upon a key economic observation that Monaghan also offers for justification of the typology.

“If you look at the ratio between elevational area and plan area on a traditional terraced house, the back-to-back version is much more efficient as it essentially halves the amount of elevation required for the same size house.

This makes it a much more efficient and cost-effective proposition,” he says.

Monaghan also cites orientation as a key driver for the back-to-back choice, pointing out that had flats been built on the site, half of them would have been north-facing and single-aspect, a far from desirable accommodation solution.

The townscape, cost and orientation considerations might explain why the back-to-back concept was chosen as the design solution for this site, but there are other ingredients that demonstrate how the typology was made to work. One of the most important of these refers to the building footprint.

Unlike traditional back-to-backs, which were historically sometimes less than 4m in width, the homes at Signal Townhouses are a generous 6m. This obviously leads to more spacious internal dimensions, combatting a key criticism of historic back-to-back housing.

Additionally, the townhouse footprints are L-shaped rather than rectangular, which means that they incorporate a deep recess in their frontages. Not only does this animate a potentially flat streetscape, but it also cleverly increases the amount of elevational surface area available for windows. By optimising the amount of windows on the elevations and ensuring that the windows themselves are large and commonly of floor-to-ceiling height, the floor plans combat yet another core criticism of back-to-back by maximising the amount of daylight admitted.

Increased amenity space

The L-shape also resolves another longstanding back-to-back problem: the lack of amenity space. Obviously, back-to-back housing replaces what would traditionally be a rear garden with another house – theoretically a clear violation of modern amenity standards.

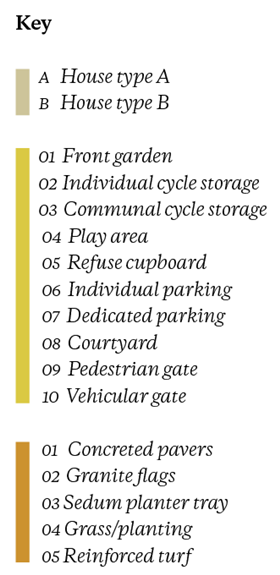

But Signal Townhouses gets round the problem by utilising the L configuration to allow space for a ground-floor terrace for each home to be inserted into the frontage’s deep recesses. This also establishes a staggered pattern of recessed terraces on the upper floors of the building, all culminating in a generous roof terrace that occupies more than one-third of the top floor. As well as this, the mews onto which each row of townhouses faces is configured as a communal hard-landscaped courtyard, which discreetly allows space for parking and bins.

Internally, the floor plan too works hard to address the flaws of historic back-to-back housing and establish its creditability as a modern residential solution. There are just two house types used across the site, and in the main they are very similar. Both feature a front door placed on the side wall of the L-shaped frontage, near to the angle of the L. This cleverly ensures that the darkest corner of the front elevation is occupied by a door rather than a window.

It also ensures the front door is near the centre of the plan, opening into a generous open-plan area that features a kitchen to the left (along the front facade and thereby benefiting from generous daylight) and a living area to the right overlooking the recessed terrace.

But the one key area in which the two house types differ is the staircase. One type features a dog-leg staircase running the full height of the building, while the other reveals a single-flight staircase to the first floor with a separate dog-leg to the second.

Arguably, the second configuration is the more ingenious of the two. This allows for the insertion of a rooflight above the lower staircase, which admits yet more light into the interior, filtered right into the living area through a perforated timber staircase screen.

But the key feature unifying both options is that the staircases are always placed right at the back of the plan, which in back-to-back housing is always the darkest internal point. By placing the staircase here – and in the second configuration even allowing a rooflight to punctuate this area – the design skilfully ensures the area of the house that potentially benefits least from natural light is filled with circulation rather than habitable space. In so doing, yet another intrinsic limitation of back-to-back housing is reversed.

Monaghan speaks of “creating another version of a typical townhouse that is part of a new typology of back-to-back housing”, and at Signal Townhouses it is difficult to deny that this is exactly what has been achieved. In market terms the transition has already been achieved. Back-to-back housing was traditionally associated with low-income accommodation, but at Signal Townhouses all 16 properties are for market sale and prices start at £875,000.

For some, back-to-back housing will always be too socially, architecturally and environmentally tainted to ever again be considered a widely accepted residential design solution. But Signal Townhouses proves that skilful design and inspired reinvention can rehabilitate even what was once the most toxic of architectural typologies.

Project Team

Architect: AHMM

Client: U+I

Main contractor: Weston Homes

Structural engineer: Walsh Group

Services engineer: XCO2 Energy

QS: Quantem Consulting

Landscape architect: East/Plan-it

No comments yet