Rather than get too excited by whizzy green technology for new homes, we should focus our efforts on the 21 million houses built before 1980. But will homeowners be ready to make the effort?

The inescapable rise of the sustainability agenda has coincided with government pronouncements including the £60,000 house competition (Design for Manufacture), the carbon neutral house competition (the Carbon Challenge), a 60% reduction in carbon emissions by 2050 and 3 million new homes by 2020. It is not surprising therefore that most news coverage has focused on new homes and the latest sexy green technology they can feature. Eco-bling has captured the imagination and in a game of sustainability Top Trumps, solar panels and wind turbines will leave loft lagging, cavity wall insulation and double glazing for dead in just about every category except actual performance.

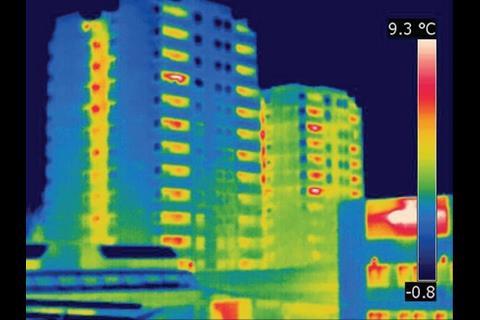

But this focus can be dangerously simplistic. Great Britain has approximately 25 million individual homes of which nearly 21 million were built before 1980. If we are to respond effectively to the environmental challenges ahead, the energy efficiency of these buildings has to be brought up to scratch. Frankly, the carbon footprint of new homes is irrelevant if existing homes (which produce 27% of all carbon emissions) are left behind. It is a fact that 70% of all houses that will exist in 2050 have already been built, but the DCLG’s 2006 Review of the Sustainability of Existing ��ɫ����TVs presents a sorry picture:

- 6.1m homes lack adequate loft insulation

- 8.5m homes have uninsulated cavity walls

- 7.5m homes with solid external walls could be insulated.

If this were addressed (and the first two measures have the shortest payback of any improvements), up to 8.5 million tonnes of carbon (1.5% of total emissions) could potentially be saved annually. But, as a footnote in the 2006 budget revealed, 95% of owners believe their home to be OK.

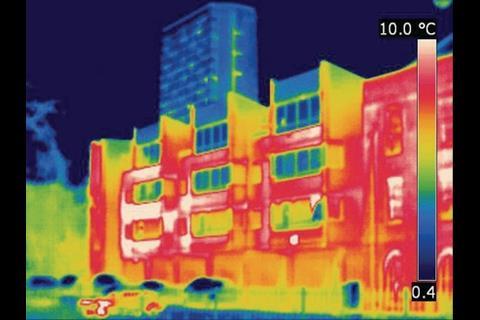

The national standard assessment procedure (SAP) ratings for calculating a home’s energy efficiency and costs give further proof of the problem. SAPs are scored on a scale from 1 (highly inefficient) to 100+ (highly efficient). To be deemed “energy efficient” a home must score at least 80 but current social stock averages 57.4 and private stock 46.8. Most new homes score 80+ with many reaching 100+. In other words, and allowing for SAPs being a little broad-brush, the vast majority of our existing stock falls considerably short (see charts).

In 2006 the Housing Health and Safety Rating System (HHSRS) replaced the Housing Fitness Standard and assesses “29 categories of housing hazard” including “excess heat/cold”. It is therefore a risk assessment, rather than ecological, measure but its requirements for E E efficient heating and ventilation include such measures as structural thermal insulation; the option of south-facing glazing to increase solar heat gain and individual heating controls. More important, it is now the “statutory component” for Decent Homes. The standard did not, and still does not, include any measures aimed specifically at sustainability though it does stipulate that a home must meet “thermal comfort criteria” through effective insulation and efficient heating. Registered social landlords have also been encouraged, though not compelled, to exceed the standard and install extra insulation, double glazing, new condensing boilers and to “consider” using low carbon, renewable or other innovative technologies.

The adoption of HHSRS has made it harder to meet the thermal comfort criteria and, as a result, the 2006 English Housing Condition Survey (January 2008) shows that more than 3 million private and more than 750,000 social dwellings fail for this reason.

However, it should be remembered that failure is due more to heat not being provided than to it being wasted so meeting the criteria may well increase total energy expenditure rather than reduce it. That estimates for the number of people living in fuel poverty are as high as 4 million also indicates that total domestic energy consumption could rise.

It costs £25,000 to retro-fit a home with an extensive compliment of green and energy-saving measures for an annual saving of less than £500

So, yes, the Decent Homes standard could have been more vigorous, but there is no doubt that a home brought up to meet it will be more energy efficient. Just a few RSLs will fail to comply by 2010 and while approximately 30% of social housing remains non-Decent, the figure is slightly higher in the private sector where rental properties are the worst performing of all, with approximately 40% failing. As the sector is not obliged to implement the standard, major improvement is not guaranteed though local authorities can force private landlords to meet HHSRS. Fortunately, these properties only represent 4.5% of total stock.

The 1.25 million owner-occupied semis, detached houses and bungalows are of more concern. Accounting for 55% of all properties with a SAP rating of 30 or lower, many owners simply compensate by turning up the thermostat and/or leaving the heating on for longer. Indeed, energy remains cheap enough for many to waste and the difference in energy costs for average usage between two identical three-bed semis with SAP scores of 45 and 90 is likely to be only a few hundred pounds a year.

So what can be done? In the social sector, though environmental grants and funding remain available, it seems unlikely a sustainability drive covering existing stock on the scale of Decent Homes will be implemented in the near future. The private sector accounts for 82% of the total housing stock and is far more problematic. The driver is likely to remain cost and payback rather than any altruistic concern for the environment, especially in the absence of legislation to enforce improvements.

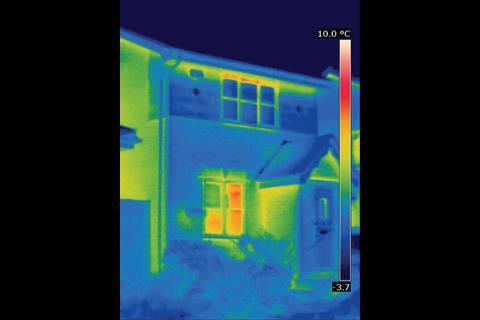

A Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors’ recent report shows that it costs approximately £25,000 to retro-fit an average existing home with an extensive compliment of green and energy-saving measures from insulation to solar panels – for an annual saving of less than £500. Given that, on average, people move every 14 years (and about 20% every three years), a 50-year payback is not especially enticing. So while the British Research Establishment (BRE) has estimated that 19 million homes are suitable for solar panels and 10 million for photovoltaics, as long as the payback period exceeds both the lifetime of the technology and the average occupancy, take-up is likely to be slow and is not being helped by applications for grants continuing to outstrip the funds available.

Other innovations will help, but only marginally. For example, domestic LED lighting will offer genuine energy savings, but their widespread adoption is some time away. Fortunately, new white and brown goods minus a stand-by will be in the shops much sooner – but their efficiency is unlikely to compensate for the growing demand for those very appliances. Heavy demand from China is pushing down the price of photovoltaics, but even BRE’s best estimate suggests they will still have a 14-year payback in 2050.

Home sellers and landlords seem more willing to entice takers with the aroma of freshly brewed coffee than by an extra layer of loft insulation. Nor do many purchasers or private tenants appear especially put off by a low SAP rating. Until there is a significant financial advantage to improve a dwelling (perhaps linking Stamp Duty to Energy Performance), things are unlikely to change. On a positive note, global warming may render older brick and stone built (thermal mass) stock more energy efficient but in the meantime, the stark conclusion remains that, in the absence of legislation, real improvement will probably only come when energy costs rise exponentially and/or attitudes change and a low SAP rating becomes socially unacceptable.

Source

RegenerateLive

Postscript

Terry Keech and Stuart Buckley specialise in sustainability and Decent Homes at calfordseaden

No comments yet