Construction companies are going bust at the rate of about one every 36 hours and regional contractors are under particular strain. Dave Rogers reports on the reasons for their demise â and what others are doing to buck the trend

David Chambers has a story for our times.

The 63-year-old chair of Lindum, the ÂŁ164m turnover Lincoln contractor set up by his father John more than 60 years ago, is talking about the spate of high-profile collapses which have bedevilled the sector over the past year.

He stops and recalls his own firmâs apparent brush with the grim reaper. The manager in charge of its office in Peterborough had shut early one Friday afternoon last August. Suddenly, the firmâs head office was getting calls from panicked suppliers. âThey thought weâd gone bust.â

Glyn Mummery is a partner at FRP Advisory, the firm handling the administrations of two of those casualties to hit the headlines in 2019 â Simons Group and Shaylor, which between them had accumulated 125 years of trading.

Mummery, who began his career 30 years ago in the teeth of the recession of the early 1990s, says modern-day collapses are almost always aided and abetted by the rumour mill. âThe speed of the rumour mill can be ferocious,â he says. âIf there is a cash pinch and creditors go unpaid, people can start sharing information [on their mobile phones] and the speed at which a business can decline is frightening.â

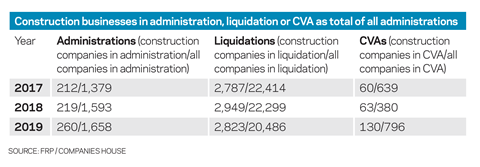

Data produced by FRP shows just how precarious being in the construction industry really is. Using Companies House records, the firm claims that last year the industry was responsible for the second-highest number of administrations across 20 sectors analysed â only manufacturing fared worse. In the past three years, construction has remained in the top three of worst-performing sectors for administrations, along with manufacturing and retail.

In the last quarter of last year, 57 construction firms went under â a rate of roughly one every 36 hours

Insolvency specialist Begbies Traynor said last week that construction and property accounted for the steepest rise in financially distressed firms â those companies that have county court judgments against them â for the last quarter of 2019. And KPMG says that in the last quarter of last year, 57 construction firms went under â a rate of roughly one every 36 hours.

Steve Absolom, a partner at KPMGâs restructuring practice, says: âWe saw decisions on investment and capital projects delayed in the run-up to the general election. That, coupled with a question mark around the UKâs position on Brexit, prompted a number of businesses that had already been teetering on the edge of insolvency to run out of cash to keep afloat.â

âBrexit is a factor but there are others as well,â says FRPâs Mummery. âWeak management, weak management information and [lack of] cash in the business.â He says firms have been trying to find work in non-core areas when work in their traditional markets has become harder to win. âThey find the skillset isnât there.â

Sticking to your knitting

One firm which knows all about this is Interserve, which did exactly that with its foray into the world of energy-from-waste (EfW) â a sector in which Clugston, another firm that collapsed last year, was also heavily involved. Saddled with a huge debt and losses of more than ÂŁ200m on the EfW schemes, Interserve collapsed into a pre-pack administration last March. It restructured and split into three businesses with one, its construction business, headed by Paul Gandy who was appointed last September.

[Regional firms] have brought in external leadership rather than family and overreached on competency and geography

Paul Gandy, Interserve

Gandy says his ÂŁ450m turnover business is a regional contractor and has a view on why some regional firms have hit the buffers. âI think theyâve overreached themselves, theyâre a certain size, want to be bigger and for various reasons have brought in external leadership rather than family and overreached on competency and geography.â

Gandy, whose CV includes spells working at Multiplex, Balfour Beatty, Carillion and Lendlease, adds that managers brought in from tier-one contractors can often send a smaller firm down the road to oblivion. âThey might have been in charge of a ÂŁ300m construction business and now theyâre in charge of a ÂŁ50m one. They might think âthis needs to growâ.â He adds: âIf they stuck to their knitting, they might still be here.â

Bringing in outsiders to run a business can mean relationships with clients become irreparably damaged, Lindumâs Chambers says. âA lot of firms [which have gone under] have chief executives from outside the family and, when I say âfamilyâ, I mean the company family,â he adds. âNational contractors who are involved in those companies are not understanding what a regional player has to have â which is, if they take on work, they need to know their client.

âAlmost all jobs, in some way, do go wrong and you need to be able to get on the phone to your client and have a proper discussion.â

Financing

Looming over all of this, though, is the waning appetite of banks to keep bankrolling contractors. Laing OâRourkeâs group finance director Stewart McIntyre spoke to șĂÉ«ÏÈÉúTV last week about just how difficult it was getting the firmâs banks to agree to a refinancing. âBanks are trying to reduce their exposure to construction,â says Cenkos analyst Kevin Cammack. âItâs not easy [for a firm] convincing the local bank manager, whoâs been given instructions by head office to reduce the construction book, to stick with them.â

Cammack says regional firms, like their larger peers, have been hit by the structural changes going on in the sector. âItâs much harder to get pre-payment and upfront payments than in the past.â All this means less money coming in and, for firms with fixed overheads, more money going out. âWhat brings a business down is cash flow.â

Ian Marson, UK head of construction at accounting giant EY, says: âThe regional construction firms are just as exposed to the challenges in the sector as the big tier ones â with working capital shortfalls and financing constraints increasingly coming to a head.â

He says initiatives such as the prompt payment code (PPC) â nominally a good thing as it compels tier-one contractors to pay up more quickly â have caused some headaches for regional firms. âPPC suspensions arenât typically an issue for most regional firms, and the changes should eventually be of benefit to subcontractors when they have worked through,â he says. â[But] the adjustment dynamics themselves are causing tightening against available financing, which is still very tight.â

Marson says that those firms which work for the bigger contractors are also feeling the pinch from the efficiency initiatives being rolled out higher up the supply chain. âMany regional firms that take on subcontract work are also now being actively impacted by the cost reduction programmes that are well under way in the main contractors, which have moved beyond the lower hanging fruits of internal headcount removal, into a wider supply chain focus to control costs and challenge invoices â potentially further increasing payment days.â

Mark Beard is the chairman of Beard, another well-known regional firm, which was set up in 1892 by his great grandfather Edward, who was just 14 at the time. The firm now employs 320 people from four offices in southern England and has a turnover of ÂŁ160m. Beard, who is due to become the president of the CIOB this summer, says regional firms need to keep things simple. âYou need loyal staff, a loyal supply chain. These are the basics you have to get right. Paying the supply chain on time gets their goodwill.â

We like to churn out 2% year-on-year and reinvest the profit rather than take it out

Mark Beard, Beard

He also says that some firms can become too obsessed with trying to improve margins to unobtainable levels. âOur ambition is to make 2%-plus margins year-on-year and weâve done that for the last 10 years.

âWe like to churn out 2% year-on-year and reinvest the profit rather than take it out. People who go on about 3%, 4% or 5% are sowing the seeds of their own demise.â

KPMGâs Absolom says the pursuit of turnover to cover overheads means margins feel the pinch and the number of problem contracts for regional firms pile up as a consequence. âThis has exposed them to disputes that negatively impact their top and bottom lines.â

After it was appointed to handle Simonsâ collapse at the end of October last year, FRPâs joint administrator Nathan Jones mentioned âcontract delays result[ing] in unsustainable cash flow difficultiesâ.

Just before Christmas, when Manchester firm Bardsley slipped into administration with the loss of 200 jobs, the joint administrators at Duff & Phelps also made reference to the firmâs disputes with clients as a reason for its demise.

And, announcing a rejig last month, Rugby-based Stepnell, whose construction business posted a pre-tax profit of just ÂŁ50,000 on turnover of ÂŁ164m, said it had been hit by âdifficulties experienced in closing certain larger contracts, where there had been significant client variations resulting in substantial additional works and consequential delaysâ. Stepnellâs joint managing director Tom Wakeford promised: âWe will be more selective about the projects that we bid for.â

The perils of uncertainty

Most agree that political uncertainty caused by Brexit has not helped. EYâs Marson says: âThe uncertainty of the past couple of years has meant many clients have cut down or delayed plans, which has resulted in a prolonged stagnation. This has been exceptionally challenging for many smaller firms to try and trade through, especially given the ongoing rise in input costs both labour and materials.â

Laing OâRourkeâs McIntyre adds: âUncertainty is a really dangerous thing. When was the last new hospital project awarded?â

The result of the general election, though, is encouraging some to think that some sort of normality is returning. Beard reckons it will take another year for firms to feel more comfortable, a sentiment echoed by FRPâs Mummery. âThe election has given certainty, people can make decisions knowing Brexit is happening. Indecision is the biggest crime of all. Firms plan start dates and staged payments. Delays make a mockery of that.â

Management teams at struggling firms need to make their lenders aware of the problems as soon as they surface

Still, an 80-seat majority for Boris Johnson will not suddenly wipe out the threats facing firms overnight. âWell respected contractors can fall over,â Mummery warns.

So what to do? He says management teams at struggling firms need to make their lenders aware of the problems as soon as they surface. âAs long as they have good management information that they can rely on, [a firm] can put forward a case to protect the business and turn it around.

âMore sophisticated management teams will get in early with the banks.â

Mummery says that banks âare more supportive than they used to be, so long as you go to them and demonstrate where you are and keep them in the loop. Do not feel embarrassed about getting advice [from specialist restructuring firms] early.

âDoing so means there is a far greater chance of turning the business around and avoiding problems.â

Staying in business â how not to blow it

Lindum will record its 12th straight year of profit when it publishes its annual results later this spring. Turnover was ÂŁ86m in 2008, growing to ÂŁ164m by the time it filed its lastest set of results for the year to November 2018. Growth, in other words, has been steady rather than spectacular. Typical jobs average around ÂŁ5m.

The firmâs chairman, David Chambers, has been in the post since 1991 and is happy to eschew big schemes, saying: âIf we had five ÂŁ20m jobs, it probably means we donât know the clients because theyâre choosing anybody. Itâs not a good way, it wants to be on the basis of relationships really.â

He says firms can too easily fall into a trap of taking on too much work if things are going well. âOften there is too much work out there and thatâs the problem, of course, because if youâre doing well, people start to think youâre quite good and like anything they start to give you more work and suddenly you end up too busy and of course then you blow it.â

The firm has around 680 staff, with its contracting business its biggest division â accounting for ÂŁ133m of revenue. It also has a land and development business, waste recycling arm, owns its own plant and carries out vehicle servicing for, among others, Lincolnshire Fire and Rescue.

Chambers sees CVs from potential employees asking for more money than he earns. âI think company directors are really bad sometimes in that they take too much and theyâre greedy. Iâm not quite sure what they spend it on. If you make any money, you need to leave some in the company to make sure that you carry on.â

How does he deal with those who ask for eye-watering salaries, then? âYou have to be polite,â he says. âI just donât want to see them. They donât see the need to be involved closely.â

By contrast, even though his two sons hold senior positions there, he remains very much involved. âI do it deliberately because I want people to feel like weâre not just one of these companies thatâs working for a chairman who doesnât know what heâs doing.â

No comments yet