Simon Henley and Gavin Hale-Brown met at the University of Liverpool in 1986 and have been friends ever since, forming their award-winning practice together in 1995. Here the pair tell Ben Flatman about their early influences, design philosophy, and commitment to improving access to the profession

We often forget that the origins of many successful architectural practices lie in happenstance ŌĆō a fortunate coincidence or shared formative experience. For Simon Henley and Gavin Hale-Brown, founding principals of award-winning Henley Halebrown, who have been working together for almost three decades, this moment was their meeting at Liverpool School of Architecture in the mid-1980s.

It was a time when Liverpool was on its knees, but full of latent opportunity, and exciting architectural horizons seemed to be opening up, especially internationally.

The pair met in their first year at the University of Liverpool in 1986, where they both studied for their Parts 1 and 2. This was a time when the west coast of America and Japan were attracting particular attention.

For Henley, the draw of the US was not so much the emerging LA scene of Eric Owen Moss and Morphosis, but the mid-century modernism and Californian work of Louis Kahn. Meanwhile, Hale-BrownŌĆÖs gaze was focused eastwards, towards the unique blend of modernism and traditional craftsmanship that had evolved in Japan.

Liverpool

But before the travelling came the fundamentals of a rigorous grounding in building and architectural history, all experienced amid the faded grandeur and chronic decay of 1980s Liverpool. Henley Halebrown is now among the most-respected London-based practices, but both men still speak fondly and animatedly about their formative experiences in the great Merseyside port city, sharing references to old tutors, and the lessons they learnt together.

ŌĆ£It was almost post-apocalyptic,ŌĆØ says Henley of Liverpool at that time. ŌĆ£It was just after the riots,ŌĆØ adds Hale-Brown, ŌĆ£and the rate of population decline was so rapid that the predictions were that the last person would leave Liverpool in 2020-21.

ŌĆ£But we had some really good teachers,ŌĆØ he adds, singling out Peter Richardson for his lectures on construction and the commonplace flaws young architects could expect to encounter in their careers. ŌĆ£Every single building has a flaw, and each of his lectures focused on a single building and on the things that went wrong.

ŌĆ£These were the best lectures you ever had. And we can still remember all of them ŌĆō all the potential mishaps that he made us aware of.ŌĆØ

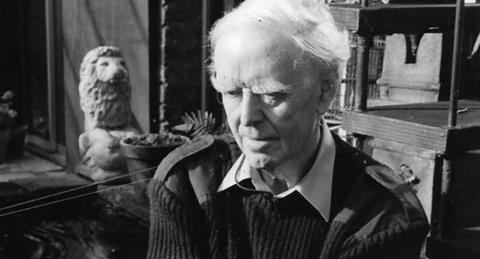

They both also fondly recall Quentin Hughes, a long-serving member of the architecture faculty, who had been a member of the SAS during the Second World War and would later help to secure LiverpoolŌĆÖs (now rescinded) UNESCO world heritage site status. ŌĆ£He was an amazing man,ŌĆØ says Hale-Brown of the respected academic.

It had this legacy of all this extraordinary stuff, most of which people didnŌĆÖt know what the hell to do with. So it all just sat there. It was an extraordinary city, but it was completely on its knees

Simon Henley on Liverpool in the 1980s

ŌĆ£He had been blown up during a night-time raid on a German airfield, had one eye and limped.ŌĆØ

And, in their third year, they were taught postwar British architecture by David Thistlewood, covering the emergence of the Independent Group, as well as the relationship to Team Ten and parallel traditions on the continent.

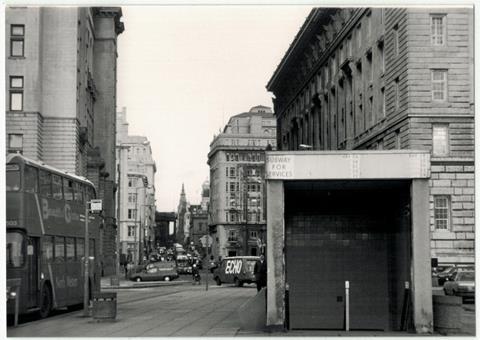

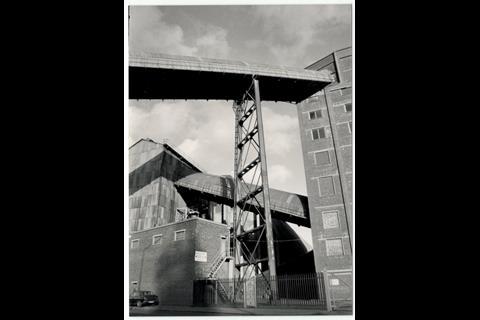

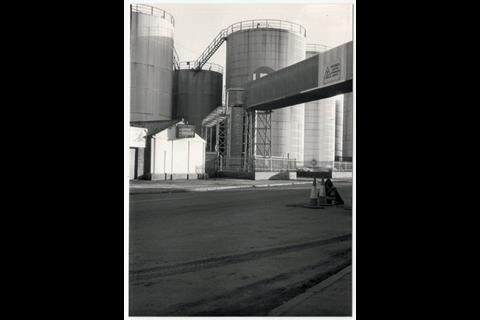

They also clearly gained a huge amount from soaking up their context. Henley refers to the imposing commercial office buildings and the industrial architecture ŌĆō much of it now demolished ŌĆō of the port, while Hale-Brown points out the way in which LiverpoolŌĆÖs late 19th and early 20th-century architecture had a powerful influence on the emergence of modernism, in Chicago in particular.

ŌĆ£It had this legacy of all this extraordinary stuff, most of which people didnŌĆÖt know what the hell to do with. So it all just sat there. It was an extraordinary city, but it was completely on its knees,ŌĆØ Henley explains.

ŌĆ£There were great swathes of Toxteth that were just abandoned, burnt out. They had flattened lots of urban blocks, so you literally saw streets just going through an empty landscape.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£It was quite incredible,ŌĆØ says Hale-Brown, ŌĆ£but that left us with Georgian houses to live in ŌĆō just ludicrous five-storey houses which had nightclubs. It was absolutely fascinating. And, at the dockside, we used to have parties in what are now grade I listed buildings, because you could.ŌĆØ

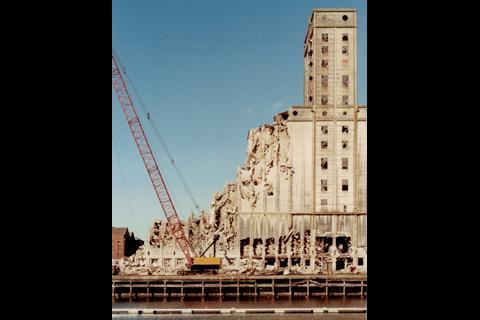

ŌĆ£That heritage of dock buildings was fantastic,ŌĆØ Henley says, ŌĆ£but what we tragically saw was the silos ŌĆō these fantastic industrial cathedrals ŌĆō being taken down, which was shocking.ŌĆØ

As they both note, the city has mounted a formidable recovery in recent years, although it still faces significant challenges. A key turning point, as so often in the regeneration of struggling cities, was the decision to start celebrating LiverpoolŌĆÖs architectural heritage, rather than demolish it. Henley identifies the opening of StirlingŌĆÖs Tate Liverpool in the Albert Dock in 1988 as a pivotal moment.

It is clear that the lessons they learnt during this period ŌĆō both formally and informally ŌĆō have been critical to their development as architects who value both the technical process of building, and the wider cultural significance of architectural practice. The re-use of existing buildings has also fed into their own practice.

Returning to LiverpoolŌĆÖs architectural influence, Henley points out: ŌĆ£There was this very strong connection to America because, although it wasnŌĆÖt an industrial city, it was a port. It had a really strong insurance and assurance business. I think it historically had the biggest financial district outside of London ŌĆō there were these two great legacies of the dock and the financial services that sat alongside them.ŌĆØ

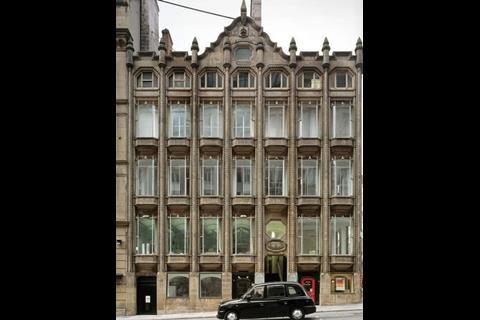

ŌĆ£There were all sorts of good buildings but there was one architect called Peter Ellis who produced two amazing office buildings, one of which was called the Oriel Chambers,ŌĆØ explains Henley. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs basically a facade of glass oriel windows. ThatŌĆÖs pretty amazing.

ŌĆ£You could see how this architecture was heading out towards the rest of the world. One assumes that the architecture of the US grew out of North America, but there is this strong heritage connection with Liverpool.ŌĆØ

A budding partnership

After completing their Part 1 studies in Liverpool, they headed south for their year-out work placements. ŌĆ£We both came down to London together,ŌĆØ explains Henley. ŌĆ£We did our year-outs down here and actually started doing competitions together then.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£We have been working together since we were 19,ŌĆØ Hale-Brown adds. ŌĆ£We did the competitions while working at two offices in London. We would be up until two oŌĆÖclock in the morning, printing stuff out and driving around the city in a Fiat 500.

ŌĆ£We presented competitions and got my girlfriend ŌĆō whoŌĆÖs now my wife ŌĆō to judge them,ŌĆØ Hale-Brown continues. Did they win any of those early competitions?

ŌĆ£Of course, not!ŌĆØ says Henley. But the experience was clearly foundational in cementing their professional relationship.

At the time, Henley was working at CZWG. He attributes his getting a job there to a particular student project that he presented at his interview with Piers Gough.

ŌĆ£Probably part of the reason Piers and I got on was I designed a corset carpark to sit on Liverpool docks,ŌĆØ he explains. ŌĆ£If you imagine a split-level multistorey carpark and you imagine a corset, and you pull the floors apart and tie them back together again with the ramps, which act like the laces ŌĆō that is what I showed to Piers.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£Obviously I thought CZWG was one of the places that I wanted to work, and of course I got my portfolio out and he was like, ŌĆśthatŌĆÖs good, you can have a jobŌĆÖ!ŌĆØ

Henley enjoyed his first six months but then increasingly found aspects of the work frustrating. ŌĆ£But, with 30 years of hindsight, you realise they were just dealing with many of the same challenges that we have to deal with.ŌĆØ

Hale-Brown spent his year out at Alan Power Architects, a small west London practice. ŌĆ£In my year-out I was getting to do everything,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£We had quite different experiences.ŌĆØ

The United States and Japan

After his year-out in practice, Henley took advantage of the opportunity to spend the first year of his Part 2 in the US, studying in Eugene, Oregon. At the end of the year, he set off on a 13,500-mile road trip, criss-crossing the country, taking in Louis Kahn buildings and much else.

ŌĆ£One of the things which has been a great inspiration has been all the places we went to early on,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£There are so many things that influence what weŌĆÖve done in practice.

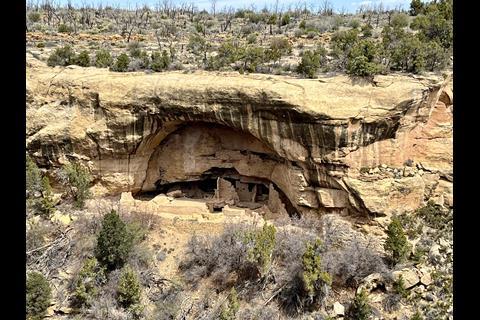

ŌĆ£Perhaps naively, but also perhaps because of the zeitgeist, I was fortunate to be very close to LA. My view of architecture has been hugely influenced by mid-20th century American architecture, but also the landscapes, and the Anasazi American Indian settlement structures in certain places like Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde.

ŌĆ£T│¾┤Ū▓§▒ Anasazi sites teach you really key environmental ideas,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£They farmed the mesa top because it was closer to the sky, because thatŌĆÖs where the precipitation was, due to the microclimate. And they would climb down ladders from the mesa top where the cliff overhangs and build a village. During winter, the low-angle sun would hit the village and warm it up, while during summer the overhang would shade it ŌĆō utter genius.ŌĆØ

Meanwhile, Hale-Brown had decided to remain in Liverpool, delaying his travels until after finishing his Part 2. ŌĆ£Going from Liverpool to Japan was fascinating,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£There was a bubble economy there at the time. Everything was getting built and demolished, built and demolished. I worked right out in the sticks in a place called Yonago.ŌĆØ

The whole construction industry is set up to deliver the building the architect designs. They just want to build what youŌĆÖve designed and find a way of building it, which is just a breath of fresh air

Gavin Hale-Brown on the benefits of working in Japan

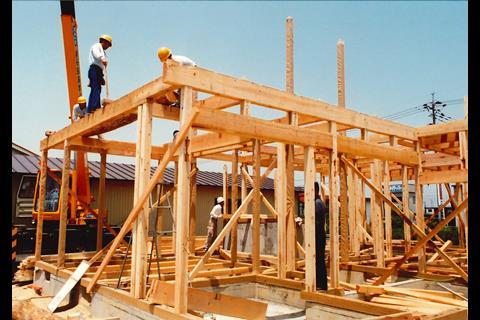

He worked for the townŌĆÖs local architect, called Kinemura & Associates. ŌĆ£You wonŌĆÖt find him anywhere ŌĆō just the local architect. Everything was focused on detail. I built traditional houses, working in timber.

ŌĆ£You would work on a house and map it out on the basis of a tatami mat, and then youŌĆÖd go to the joiner, who would turn up on site with everything already cut.

ŌĆ£They would have cast the foundation and then the frame gets dropped in. ItŌĆÖs just logs and beams and it smells wonderful. And the joiners have two-toed soft shoes so they can climb up the frame, and they just knock it all together. By the end of the day, youŌĆÖve got a two or three-storey house.

ŌĆ£This was all cut off-site and it was all pre computers. Everything was drawn by hand and cut by hand and they just knocked it together with big mallets. There were no mechanical joints. And every time it just worked.ŌĆØ

Hale-Brown still clearly marvels at the precision of the work that he witnessed. ŌĆ£The Japanese work with incredible contractors that we do lack here in the UK, although weŌĆÖre probably getting to work with better contractors now.

ŌĆ£There the whole construction industry is set up to deliver the building the architect designs,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£They just want to build what youŌĆÖve designed and find a way of building it, which is just a breath of fresh air.ŌĆØ

Practice

It was on Hale-BrownŌĆÖs return to the UK that they set up the practice, which was founded in 1995. Looking back to the early years of collaborating on competition entries, Hale-Brown observes: ŌĆ£We still work in the same fashion, although we lead on different things, but we donŌĆÖt silo the practice.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£We work on everything together, pretty much,ŌĆØ says Henley, ŌĆ£although Gav does know his way round a contract better than me.ŌĆØ

There have been other directors, including Ralph Buschow and Ken Rorrison, both of who played key roles in the early development of the practice, but who have since moved on.

To help ensure the smooth day to day operation of the practice, Henley Halebrown has now had an office manager for 16 years, but it has never grown larger than around 35 people. ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖve hovered around 25-30 for 20 yearsŌĆØ, says Henley.

ŌĆ£Having done this now for 29 years, and occasionally got up to 35 and occasionally got down to a dozen, I donŌĆÖt think either of us can pretend that weŌĆÖre growing this business to be enormous,ŌĆÖŌĆÖ says Henley. ŌĆ£And weŌĆÖve never wanted to,ŌĆØ Hale-Brown adds.

Maintaining a manageable size where they can both remain meaningfully engaged in projects remains key to the practiceŌĆÖs approach. ŌĆ£I think part of it is that you can maintain a level of curiosity if youŌĆÖre hands on,ŌĆØ says Henley. ŌĆ£As a practice we also teach and write, and we think all these things are inter-related.

ŌĆ£We are acutely aware of the cultural side of practice. While we are a business, weŌĆÖre really interested in each project. The benefit of not doing too many is that you can still have an ambition for that project that you can discern from the next.ŌĆØ

If you look at our work, youŌĆÖd see a lot of care in how you plan, detail and build a building. But what underpins all of the work is the social logic. In a way it is social work

Hale-Brown on the pairŌĆÖs philosophy

Henley also believes that one of their key strengths as a practice is their understanding of work environments, with each project and client informing their approach to the next commission. ŌĆ£What we learnt from working for a client like WPP [the advertising agency], with their 600 staff, influenced how we worked with healthcare clients, and understanding how their organisation worked. And then you do a school and actually learn how a school works together.

ŌĆ£What we find is that, by doing a mixture of types, they all inform each other. And, if you look at our portfolio, weŌĆÖre not one-dimensional. WeŌĆÖre not housing architects, weŌĆÖre not healthcare architects, although weŌĆÖve done a lot of both. We produce a lot of work environments, eschewing fashion and trying to understand how people work together.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£I think, if you look at our work youŌĆÖd see a lot of care in how you plan, detail and build a building,ŌĆØ says Hale-Brown. ŌĆ£But what underpins all of the work is the social logic.

ŌĆ£In a way it is social work. We are genuinely interested in how people use buildings.ŌĆØ

Henley describes the approach as being about ŌĆ£beneficial buildingŌĆØ ŌĆō a concept that he has been advocating at Kingston University, where he teaches. ŌĆ£That could be taken to be very prosaic but, if you think of what you really mean by something being ŌĆśbeneficialŌĆÖ ŌĆō the experience, the quality of light, the pleasure, happiness, dignity ŌĆō those are the kind of things you bring to people as an architect.ŌĆØ

Henley sees the practiceŌĆÖs emphasis on workplaces, social organisation and sustainability as recurring themes that have preoccupied them for the past three decades. ŌĆ£YouŌĆÖre always dealing with real people and real communities and people who donŌĆÖt choose to use the building ŌĆō they have to use it. ItŌĆÖs about having respect for all of those people.ŌĆØ

Many motifs and concepts reappear in their projects, including courtyards and external workspaces, and a preoccupation with natural ventilation and how people interact. ŌĆ£All those soft things that, 20 years ago, people werenŌĆÖt talking about, the market is now demanding,ŌĆØ he points out.

Hale-Brown points to how these ideas have fed through to more recent projects such as Hackney New Primary School. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs got external decks, natural ventilation and a focus on people interacting.

ŌĆ£It didnŌĆÖt overheat during the summer of 2022. When it was 40C outside, that school kept going. And the teachers could explain to the children why this was a good building from an environmental perspective because they could literally physically experience sustainability, as something that has something to do with comfort and life.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£And that comes from starting the building with how people are going to use it, where the kids are going to sit,ŌĆØ adds Hale-Brown. ŌĆ£At the school, theyŌĆÖve got deep decks so you can work outside on them. At Talkback it was the same, you can work outside.ŌĆØ

The importance of narrative

ŌĆ£I think itŌĆÖs really important that what underpins a lot of these projects is a narrativeŌĆØ, says Henley. ŌĆ£So, for example with Talkback [the TV production company based in central London], we talked about it being collegiate - almost a medieval cloister, and so that analogy was something that you could very literally use to evoke this image of a place.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£What was also really striking with Talkback was that their activities mapped very closely onto that of an academic environment. They do a lot of research, and so youŌĆÖve got this core group of very idiosyncratic and very talented older people. And then they had this through-put of very young people working in the production teams, who would work typically for six months.

ŌĆ£You could see this parallel with university culture of postgraduate researcher, and academics, and this sort of undergraduate force that flowed through the building. So we described it like that, and we described this place that, although it was only 100m away from Oxford Street, was kind of about a community of people thinking about things and making things. And we responded by giving them a social, intimate workspace, that could also take a party of a thousand people.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£The building was designed to be flexible, which now is just an obvious thing to do,ŌĆØ says Hale-Brown. ŌĆ£The four corners could be sublet, and the whole building could be divided up into five parts. We even put a residential unit at the top, which they could hive off to fund the rest of the building. That flexibility was built in.ŌĆØ

TalkbackŌĆÖs offices were recently converted into a hotel, with minimal changes, and much of Henley HalebrownŌĆÖs fabric retained ŌĆō testament to the designŌĆÖs flexibility and robustness.

ŌĆ£A lot of principles that you could trace back to Talkback keep recurring,ŌĆØ explains Henley. ŌĆ£If you look at Copper Lane [LondonŌĆÖs first co-housing scheme], and then Hackney New Primary School, more often than not we have been trying to plan a building through its relationship to outside space and certainly its relationship to a primary space.ŌĆØ

Future of the profession

Both men believe strongly in contributing back to the profession, and helping to deliver outreach and mentoring to young people. Creating a profession that is diverse and open to all is a key priority.

They are intrigued by ARBŌĆÖs proposed reforms to the education system, which ARB says are partly intended to help improve access to the profession, but not entirely convinced that the regulator has yet settled on the right model.

ŌĆ£There has to be some way of enabling more people to study architecture,ŌĆØ says Hale-Brown, ŌĆ£but whether ARBŌĆÖs reforms are the right approach is still an open question.ŌĆØ

Pointing out that the current tripartite education system dates from 1958, Halebrown observes that ŌĆ£lots of good architects who qualified before 1958 didnŌĆÖt go through a university education, so thereŌĆÖs nothing wrong with changing the model.ŌĆØ

On ARBŌĆÖs proposal to stop accrediting Part 1, Henley is sanguine, partly because he was taught within the US system, where an undergraduate degree is not a requirement to qualify as an architect. ŌĆ£It doesnŌĆÖt really seem to deprive anybody of anything because you can still do an undergraduate degree in architecture,ŌĆØ he says.

ŌĆ£When I was studying in the States, there were people who were doing an undergraduate degree in English and then they would come and do a masterŌĆÖs in architecture.ŌĆØ

Hale-Brown does express concern about the number of competencies ARB will require schools of architecture to deliver. ŌĆ£The idea theyŌĆÖve got 49 specific areas of competency, that seems a lot.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs like when we have a scope of services and someone tries to list everything that an architect does ŌĆō thatŌĆÖs not what you want to do with a scope of services. Because how do you measure those things? I do worry that itŌĆÖs easier to tick something off on a list rather than really challenge the students.ŌĆØ

He also worries that students going into an architecture masters degrees without an architectural undergraduate degree may be in for a shock. ŌĆ£I do think thereŌĆÖs a danger you end up going into a masters not understanding what an architect does.ŌĆØ

To help a younger and more diverse group enter the profession, the practice does a lot of work on outreach and mentoring. ŌĆ£We go into primary schools and we build domes with them, and we spend a day talking to them and helping them understand what an architect does,ŌĆØ says Hale-Brown, whose wife is a school teacher.

ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖve done that with years 4, 5 and 6 [eight to 11-year-olds]. And itŌĆÖs really interesting because kids really donŌĆÖt understand what an architect does. But by the end of the day a lot of them want to be architects,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£That might be good or it might be bad, but a lot of them do.

ŌĆ£And the thing where I see a real danger with ARBŌĆÖs reforms is people having done an English or history degree and thinking, actually, that architecture is really interesting, and then start doing a masters in a subject that they donŌĆÖt necessarily understand where it really takes you.

ŌĆ£Part 1 allowed you to feel your way around it. Lots of people drop out after Part 1 because they realise itŌĆÖs actually quite a hard thing to do. To be an architect is really not a straightforward thing, itŌĆÖs not like on the TV or films.ŌĆØ

Bringing in people from local schools to help them actually understand what an architect does is fundamental. You have to start right there if you want a diverse profession and to encourage people to join

Hale-Brown

For the practice, a bigger issue than education reform is the challenges their EU staff face in getting their qualifications accredited since Brexit. ŌĆ£We are funding some people to get codified,ŌĆØ says Henley, ŌĆ£but it is a vast amount of money that ARB are charging to do that process.ŌĆØ

Of a mutual recognition agreement with the EU, Hale-Brown adds: ŌĆ£ThatŌĆÖs an obvious thing to do and, from my point of view, ARB should do that first.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£There are a whole series of people for whom different things matter,ŌĆØ observes Henley. ŌĆ£Clearly thereŌĆÖs a diverse population of people who might want to be architects who might be disadvantaged, and presumably the ARB move is to address that.

ŌĆ£Then, equally, in the context of diversity, actually having a studio that has a really rich mix of people ŌĆō whether theyŌĆÖre from Europe or further afield ŌĆō thatŌĆÖs something which again, politically, within the profession, is equally important.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£ThatŌĆÖs why we also focus on 16-18 year olds,ŌĆØ explains Hale-Brown. ŌĆ£Mentoring through school, bringing them in here so they understand. There is no doubt that thereŌĆÖs nepotism in architecture. And there is no doubt that, if youŌĆÖve never met an architect, youŌĆÖve got no idea what they do.

ŌĆ£So bringing in people from local schools to help them actually understand what an architect actually does is fundamental. You kind of have to start right there if you want a diverse profession and to encourage people to join.ŌĆØ

He also welcomes new course models being developed by schools such as the London School of Architecture, and the wave of new apprenticeships. ŌĆ£I think the model of apprenticeship is much more beneficial to young people,ŌĆØ he argues. ŌĆ£They donŌĆÖt get such big debts. They get much better real experience.

ŌĆ£Mentoring people through A level is another really key thing for architects to do, which isnŌĆÖt talked about enough. WeŌĆÖve done invited competitions in London boroughs where part of the bid has to be us funding a student from 18 to Part 3,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£And thatŌĆÖs the contribution they want.

ŌĆ£That means one person gets a golden ticket. ThatŌĆÖs not going to create diversity. ItŌĆÖs got to be something that addresses the systemic issue.ŌĆØ

As the practice contemplates its approaching 30th anniversary, it is clear that Henley Halebrown remains as committed to architectureŌĆÖs wider social purpose as ever. And its founders, whose shared vision of practice was formed through early experiences in Liverpool and overseas, are focused on passing on their passion ŌĆō and knowledge ŌĆō so that a new generation can thrive.

>> Also read:

No comments yet