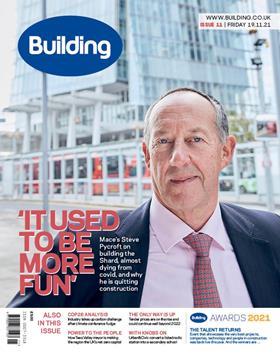

As Mace chairman Steve Pycroft prepares to bow out, he will be remembered above all else as the man who delivered the Shard â and delivered it in style. Dave Rogers talks to him about the project that changed everything.

Steve Pycroft has a word to describe things when they get a bit hairy. âIt could have got a bit tasty,â he says of the decision to build the Shard.

Others in Mace at the time were less convinced of the probity of a move to build Londonâs tallest tower for a fixed price of ÂŁ500m. âThere were discussions at board level saying, âcan we not not do this?â, âDo we need to do lump sum because there is a major concern it will send us bust?ââ

He recalls his daughter telling him after he had been discharged from a second spell in hospital with covid-19 last spring just how perilous things had got. She had managed to get a flight back from Australia, where she was travelling, to be at his bedside in spirit as visitors were banned from seeing those stricken with the virus in person.

And stricken her dad was. He spent nearly four weeks on a ward in an induced coma. Doctors later told him it was touch and go whether he would pull through. âIt was only after Iâd got out, Jessica said: âDad, you know it got fairly tastyâ.â

If Mace had a godfather, Pycroft (pictured) would be it. It is still extraordinary to comprehend that, around the year 2000, Mace had a turnover of something like ÂŁ65m and yet, seven-odd years later, was taking on a ÂŁ500m contract to build a tower whose design had already caught the public imagination because of its resemblance to a shard of glass. It could not have been a higher profile scheme for a firm to make its major contracting debut.

For those who know the 63-year-old, who is calling time on his career at the firm next month after close to 30 years at the business, what he now says about the Shard and battling coronavirus wonât surprise them a bit.

âThere was never a doubt we could build it,â he says of the tower. And his brush with death and covid-19? âI didnât think it was that life threatening.â

>> Click here to read more industry interviews

But Pyrcroft is sharp enough to know deep down that building a very tall tower for a lump sum above one of Londonâs busiest railway stations could have sent the firm under. And he also knows that he was one of the lucky ones last spring. He survived, but thousands didnât.

He is leaving Mace and construction behind, he says, because he is not enjoying it as much as he used to. âIâve fallen out of love with it a bit,â he concedes. âI used to love every minute of every day. Now it doesnât have that kind of appeal anymore. If youâre not enjoying it, stop doing it.â

Iâm a dinosaur. The dinosaurs are dying and Iâm one of them

Pycroft admits that he misses the rough and tumble of the old days, when deals could be done in a pub or over the phone.

âI wonât hide from the fact that Iâm a dinosaur. The dinosaurs are dying and Iâm one of them. When I listen to how much IT is involved on projects these days, weâre using this and doing that, using this kind of software for recruitment and I go: âYeah, itâs not me.â Iâm sad that itâs not me, but itâs not me.

âThe world has changed. Thereâs corporate governance, it is more strict on accounting since Carillion went bust.

âAccountants have got a lot more paranoid about everything and anything. The whole fun of running a business has slowly dwindled away. [Decisions are] more driven by corporates and group decisions, not by single individuals who are willing to put their head above the parapet. Thereâs too much scrutiny, criticism, question marks.â

It sounds like a lament â and some of it is â but he is self-aware enough to know that times have changed and itâs time to get out.

Strong relationships

To give an example of just how things have altered, he remembers the time he helped to put together the CLM team that was charged with making sure the venues and infrastructure for the 2012 Olympics got built.

Mace was speaking to CH2M Hill, a US company that was little-known in the UK at the time. It was interested in the Olympics role and was hoping Laing OâRourke might be too.

But there was a problem. The Americans were having difficulty getting hold of Ray OâRourke. âSo I rang Ray,â Pycroft recalls. âHe said he was up for listening, we went down to Dartford [where Laing OâRourke is based] and he said: âyeah, letâs go for itâ.â It took half a day for the joint venture to be born.

âRelationships throughout my career have always been important,â he says. None more so than perhaps his ones with developers Gerald Ronson and the late Irvine Sellar.

Ronson, who successfully rebuilt his reputation after being handed a one-year prison sentence for his role in a 1980s share trading fraud, was the developer of the Heron Tower, the KPF-designed scheme built by Skanska, where Mace was the project manager.

Ronson was sufficiently impressed because Pycroft, who counts Ronson as a personal friend, says: âGerald said: âHave a word with my little mate about a job heâs gotâ.â

That person turned out to be Irvine Sellar, who started out as a fashion retailer in Londonâs swinging 60s, later buying up the site of the Shard, then the headquarters of accountant PwC, in the late 1990s.

âIf we hadnât had a good relationship with Irvine, we wouldnât have built it,â he says. But it was Pycroftâs rapport with Sellar that was key.

âAll credit to Irvine, he said he wanted Mace. He wanted an individual he could relate to and I was lucky enough for that to be me. I got on well with Gerald, was fairly well known in the industry and that ticked boxes for Irvine.â

Sellar died four years ago but Pycroftâs relationship with the developer remains strong, turning out recently for the topping out ceremony of its Paddington Square scheme which Mace is building in west London, where he made a speech alongside Sellarâs son James.

Finances

The Shard had been in the pipeline for some years before work in earnest started in 2009. On-off for several months, Sellar eventually got through the 2007/08 crash and secured the funding needed from a consortium of Qatari investors. But Pycroft knew there would be a problem. âThe weakness was the Mace balance sheet. We didnât have one.â

Pycroft had to sweat it out as others, notably Sir Robert McAlpine and Laing OâRourke, took a look at the job. Rival interest cooled, perhaps put off because they knew Sellar would try and stick with Mace. âAll credit to Irvine because [in his discussions with the Qataris] he said: âI want Maceâ. But Mace hadnât got the balance sheet until Irvine stepped in and helped provide us with forward funding in terms of placing orders with contractors.â

Pycroft only met the Qataris a few times during the project. âThe questions were fairly direct and succinct,â he remembers. âIf there was flak to come from the Qataris, Irvine would always shield us from it. He would turn around and say: âJust make sure itâs delivered, Stephenâ.â

I know a number of others said Mace would never deliver it in the programme. We had constantly got this comment from other major contractors that we werenât regarded as one

The deal was a game-changer for Mace. Previously, its typical jobs were around ÂŁ40m and some rivals sneered at it for just being a construction manager. As the Shardâs procurement process dragged on and funding chopped and changed, Mace progressed from a project manager to a construction manager to, finally, the main contractor.

âIt put us in the premier league of construction,â Pycroft says. âThere was no doubt it was a massive surprise to some. How can Mace be doing a ÂŁ500m job? Why has Irvine supported them in delivering this? I know a number of others said Mace would never deliver it in the programme. We had constantly got this comment from other major contractors that we werenât regarded as one. âItâs alright being a CM but you never take the risk. Itâs all easy.â

âThere was a lot of verbals, lots of chit chat, âyou never have skin in the gameâ and for me it was, you know what, letâs just go and show them all what we can do. Letâs just go and show them we can deliver it. If we were going to pick a job [to do that], we may as well pick one thatâs the highest one in London.â

He adds: âI do look back and think: âWow, weâre just stepping into a ÂŁ500m, two-stage bidâ. Perhaps I should have been more twitched. If the market changes, 2% or 3% margin can just be lost on inflation.â

The outsider

If Mace was an outsider at the time, perhaps it was a reflection of where Pycroft came from. He grew up in Bradford, his interest in construction sparked by his father, Arnold, a painter and decorator. Like many who make their way to the capital from the regions, Pycroft had something to prove. âIâve been 40 years down in London. The plan was to pop down from Bradford, make a few bob and go back up North.â

He graduated as a quantity surveyor from Trent Polytechnic in the early 1980s, joining Gardiner & Theobald. He stayed there for 18 months before deciding that he didnât like it anymore. âBovis came along and said, âweâll employ you as a QS, but you will have the chance to become a project managerâ.â

His degree and experience at G&T was not to be wasted, though. âI think some of the best project managers are quantity surveyors by profession. It gives you an understanding of what is real cost and value, a bit more of a grounding in how decisions should be made.â

He remembers his first job at Bovis in a flash. â35-38b George Street in Richmond. A little cut and carve. Office and retail, ÂŁ3m to ÂŁ4m. I never looked back.â

At Bovis he met Ian Macpherson, who would later help to set up Mace in 1990, and it was Macpherson who gave him his first major project manager role at Bovis â the ITN building on Grays Inn Road in London in 1988.

Those who worked on it read like a whoâs who of the industry. Developed by Peter Rogers and Stuart Lipton when the pair were at Stanhope, QS was Davis Langdonâs Paul Morrell â later to become the governmentâs first construction tsar â the architect was Norman Foster, with those from the practice working on it including Ken Shuttleworth, later to found Make, and Grant Brooker, now its head of studio.

The late Tony Fitzpatrick, the structural engineer whizz from Arup, who would later work on the Shard, was also there. âRay OâRourke was pouring concrete,â he adds.

Macpherson left to set up Mace after Bovis began to eschew the CM route. âIan Mac said to them: âIf youâre not going to do CM anymore, Iâm going to go and form my own companyâ. So he did.â

Pycroft knew the call would come from Macpherson at some stage â he had told him to expect it â and it did, in 1993. He joined as a project manager and on his first day Macpherson sent him off to a job in Smithfield Market. âIt was a combined heat and power scheme. I thought I had come in to run a big job at Mace and Ian Mac said âpop down there for a couple of weeks and look after it, Stephenâ. A year later I emerged from the basement, two stone lighter, to eventually go and do the job I was brought in to do.â

That turned out to be 1-19 Victoria Street, a refurbishment scheme that would later become the central London base for the Department for Trade and Industry.

His rise at Mace was meteoric, leading a management buyout in 2001 when Macpherson decided to sell his one-third stake. âNone of us were business people at the time and Ian was very helpful in trying to make sure there were no major cashflow issues.â

Weâve all been on major projects that have gone wrong. We did some resi in Birmingham that cost us money, resi in Manchester that cost us money

Pyrcoft took over as chief operating officer, becoming chief executive in 2004 and executive chairman in 2008. âMe and Ian Macpherson would pinch ourselves. Did we think weâd be this ÂŁ2bn turnover company? No, not at all.â

For every Shard, the firm has had its share of schemes it would rather forget. âWeâve all been on major projects that have gone wrong. We did some resi in Birmingham that cost us money, resi in Manchester that cost us money.â

They were more than a decade ago but Pycroft cautions: âWe moved out of our power base in London and we didnât have that sway with the supply chain and it cost us money.â

In London itself, the firm lost around ÂŁ40m on the Nova office building in Victoria. Finished four years ago, the job was fixed at around ÂŁ400m but the design had not been completed and the cost of wages and materials began to outstrip what it had agreed with Landsec to build it for. âNova was probably the biggest [loss],â Pycroft says. âYou realise how fragile profits are.â

He picks the Shard as his favourite job. âIt was a time and a place with a great group of people. We all had some good fun, it was tough, but we all enjoyed it. There was rarely any recrimination or finger pointing.â

He will miss construction, the tales and the yarns, the moments that stunned the industry. Such as? OâRourke buying Laing for a pound â âthe deal of the century, Ray deserves his seat at the top tableâ â Multiplex taking on the job to rebuild Wembley stadium after its joint venture bid with Bovis disintegrated â âthere was a big gasp at thatâ â Carillion going bust â âthe senior people got too divorced from their own businessâ.

He recognises that people such as him are leaving the industry bit by bit. âTheyâre drifting away or passing away,â he says, sadly.

âItâs a lot more controlled and professional, which is good in so many ways but that comes with the removal of entrepreneurialism, a bit of fun. The mavericks are not part of that new era.â

Miss it he will, but he is adamant that he is not coming back and, in January, he returns to Yorkshire to be closer to his two older sisters and younger brother.

âIâll remain a [Mace] director, me and [chief executive] Mark Reynolds [between them they own around 50% of the business] will no doubt keep in touch, but there will be no day-to-day involvement. Iâve done enough, itâs time to walk away. Iâve put my heart and soul into Mace and itâs time to draw a line. Mace is in safe hands.â

Might he not be tempted by a non-executive role in case he misses those Mace board meetings at 8am every Monday morning a bit more than he thought? âNot interested,â he says.

He is planning more travel, has a bike ride across the Pyrenees to complete next summer and a trip to tackle Kilimanjaro, Africaâs tallest mountain, planned for later on in the year.

âI donât want to get to 70 and then stop and not be able to do anything. Iâve got my health and letâs go and enjoy it while we can. Thereâs still plenty of things to do in the world.â

Over but not out

It was a neighbour who noticed Steve Pycroft wasnât looking too good when she popped round to his house one day last March. He had come back from the US, was coughing, struggling to get up the stairs.

âShe said: âYou look shit, Stephen, Iâd better get the ambulanceâ.â And so began a stay at Wexham Hospital, near Slough, with covid-19 which saw him put into an induced coma for nearly four weeks over two stretches.

He was discharged after a couple of weeks, only to be whisked back in when he contracted pneumonia. He doesnât remember too much about the whole thing apart from being asked his name and date of birth every day when he was roused from his coma by the nurses.

The strain for his two children â Elliott, 22 and older sister by two years, Jessica â was hard. Jessica flew back from Australia, the birthplace of her late mother Joanne who died from breast cancer aged 39 in 2006, to be with her dad.

Pycroftâs spell in hospital helped him make up his mind over a decision as to when he would leave Mace. âThere were a number of things that make you question what you do,â he says. âIt had already been heading that way [to leave].â

Elliott and Jessica didnât hear much for the first few days he was in hospital. âNobody knew what was going on, which added to the anxiety and stress.â Discharged in May, it took him the rest of the year to recover. âThereâs been no post-covid issues, thoughâ he says. âIâm fortunate.â

Mace was my saviour as well. I could immerse myself in work much to the criticism of a number of people

After the death of Joanne, he threw himself into his work. âMace was my saviour as well. I could immerse myself in work, much to the criticism of a number of people because I came back fairly soon after Joanneâs death. If you immerse yourself in work, you can ignore the real world.â

There is black humour when he mentions his wifeâs reaction to the prospect of her going before him. âWe always thought I would die first with the lifestyle I lived. Work hard and play hard. She said: âThatâs the worry Stephen, Iâm leaving these two children with youâ.ââ He admits: âIt was tough for me but it was tougher for Elliott and Jessica.â

He is immensely proud of them, that much is obvious. Elliott is working at Mace as an assistant project manager and Jessica as a parliamentary researcher. âIâm more than pleased at how theyâve turned out and thatâs an understatement.â

He says Jessica has no interest in construction. âToo aggressive,â he says, though he concedes that is changing â and for the better. âThereâs rarely effing and blinding across the table anymore. Itâs just not acceptable.â

Doesnât mean he doesnât miss it, though. It is left to his son to rib him about his dadâs sometimes four-letter tirades. âHe told me I had made a career out of swearing and I said: âElliott, I made a career out of giving clear direction that was unambiguous and which everybody knewâ.â

Novemberâs issue of șĂÉ«ÏÈÉúTV

>> Read șĂÉ«ÏÈÉúTVâs latest digital edition, out today, also featuring COP26 reaction, an interview with Teessideâs mayor and details of all the șĂÉ«ÏÈÉúTV Awards 2021 finalists and winners

Steve Pycroft CV

1958 Born Bradford, West Yorkshire

1980 Graduated from Trent Polytechnic

1981 Joined Gardiner & Theobald as a QS

1983 Moved to Bovis as a QS then project manager

1993 Joined Mace

1995 Appointed Mace group board director

2001 Led management buyout, appointed Mace chief operating officer

2004 Appointed Mace chief executive

2008 Appointed Mace executive chairman

2012 Stood down as CEO

2012-21 Mace executive chairman and then group chairman

December 2021 Will stand down from company, though remains a director with a 17% share of the business

No comments yet