The 2010 Vancouver Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games has triggered a flurry of building activity ŌĆō including this Trout Lake ice rink. Stephen Kennett hurried along for a preview

With all the anticipation surrounding LondonŌĆÖs 2012 Games, it might have slipped your attention that the next event on the Olympic calendar is only 140 days away: the 2010 Vancouver Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games will kick off on 12 February. The Canadian city will host the opening and closing ceremonies as well as the ice hockey events, while speed and figure skating competitions will be held in nearby Richmond and the skiing events in the mountain resort of Whistler.

Now, any Olympic win precipitates a building boom and Canada has been no different. But it has been careful not to fritter its money away on white elephants, having learned from the mistakes of others. Eleven venues have been created in total within a construction budget of $580m (┬Ż322m). ║├╔½Ž╚╔·TV made a quick trip across the pond to find out what had been achieved so far.

Venue Trout Lake ice rink

Use Practice venue for competitors during the Games

Legacy Public ice rink and sports venue

The plan to replace the ageing community centre in VancouverŌĆÖs John Hendry Park was around before the Olympic bid. But when the bid was successful and the need for a figure skating training venue arose, there was a natural opportunity to develop the scheme for this purpose.

During the Games, Trout Lake will be a practice venue. The rink will then be retrofitted for community use. The Olympic-mode ice pad will shrink by about 5m to a standard National Hockey League-sized rink and permanent spectator seating for 250 will be installed along with playersŌĆÖ boxes.

The challenge facing the designers was how to build something that was economical and fitted in with the residential surroundings. The roof had to span 30m and the design team was keen to use timber. This could be achieved, said architect Walter Francl, but it would require a roof truss that was 2.5m deep, adding to the height of the building.

The structural engineer came up with an ingenious solution. Rather than using glulam beams to span the complete distance, it introduced a single 64m-long steel arch connected by pin joints to concrete buttresses at the north and south ends of the ice rink. This beam divides the roof in half, with one side supported on the lower flange and the other half on the upper flange. Using steel might be a slight cheat, but it enabled the architect to introduce a clerestorey window between the two roof leafs, filling the space with natural light, and giving a much softer roofline.

The tricky bit was the construction. Four cranes had to be used to hold the steel arch in place while it was pinned in position, and a further two cranes were used to lift the glulam beams, which stopped the arch from toppling over, into place.

Venue Richmond Olympic oval

Use Home of the 400m speed skating track with temporary capacity for 8,000 spectators

Legacy Multi-purpose sports venue

Every Games needs a signature structure and the oval, with its novel single-span wooden wave roof that covers an area equivalent to five football pitches, is it for Vancouver.

Funded by Richmond, the venue was key to the cityŌĆÖs long-term plan to provide improved sports facilities and put itself on the map. Unusually, the speed skating track is on the first floor, with the service and amenity areas below. The two lower floors are concrete cast in situ, with inclined concrete buttresses from which the arched roof springs. ŌĆ£It gives maximum value inside for future useŌĆØ, says Larry Podhora of architect Cannon Design.

The composite wood and steel arches span 100m, making them some of the largest structures of their type in the world. These incorporate the air conditioning ductwork and remotely controlled nozzles which fire cool air onto the spaces below to create different climatic zones, enabling flexibility for future use.

Bridging the 12.8m gap between the arches are prefabricated panels made up of 2ŌĆØ x 4ŌĆØ timbers, to give a rippled appearance. According to Podhora, this was to give the building some visual flair.

To form the V-shaped profile which curves along the panelŌĆÖs length, small timber sections from trees killed off by the mountain pine beetle were used.

This had not been tried before, so tests were conducted. Acoustically, the timber was shown to out-perform a conventional perforated metal deck and to be structurally sound. But there were concerns over how it would perform in a fire, given that the wood sections were much smaller than usual. Fire simulations confirmed they would meet Canadian building code standards, helped largely by the large volume and height of the space, which means it would take a long time for the beams to be affected.

Venue Vancouver convention centre

Use International press centre

Legacy It will go back to being a convention centre

The recently completed extension to the Vancouver convention centre was never intended as an Olympic venue, but when youŌĆÖve got a 90m x 225m exhibition hall and a triple height ballroom itŌĆÖs crying out to be used. Unlike London, which will need to find a tenant for its broadcasting centre after 2012, the Canadians will simply divide this existing building up with drylining partitioning to create scores of studios and workstations for about 7,000 broadcasters and technicians.

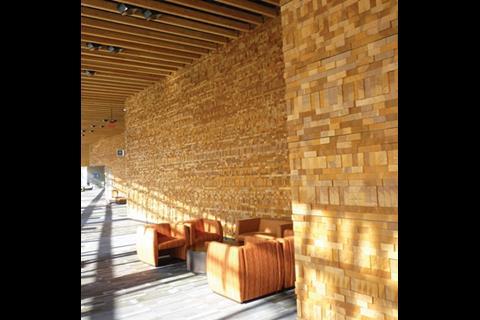

The entire ballroom of the convention centre is clad in hemlock of varying cuts to make it look like a giant stack of timber

The halls are blank canvases, so can easily transform, there is a huge kitchen and the access is designed to accommodate the lorries and standby generators needed to create a temporary broadcasting venue. The team working on the centre will have just 10 days from the end of the Games to dismantle everything and take it off site. Think of it as just another large exhibition.

The Douglas fir glulam beams span the 50m pool

Venue The Percy Norman aquatic centre

Use Curling and marshalling area for athletes

Legacy Will reopen as a multi-purpose community centre with 50m pool, ice hockey rink, gymnasium, library and six to eight sheets of curling ice

This is really two buildings in one, situated in VancouverŌĆÖs Hillcrest Park. On one side, beneath an impressive structure of curving Douglas fir, is a 50m swimming pool that is completed and ready to open to the public after the Games ŌĆō thereŌĆÖs no swimming in the Games themselves, but it made sense to build it now as part of the legacy. On the other side is an ice rink housed in a more conventional steel-framed structure.

There are some curious features on this building ŌĆō for instance, pairs of doors set high up in the walls, staircases that seem to lead nowhere and reinforcement steel poking out of the exposed concrete. Architect Michael Henderson of Hughes Condon Marler explains: ŌĆ£During the Games all these things will be hidden by large banners and the 6,000 temporary seats, but afterwards weŌĆÖll insert a mezzanine level to help transform the venue.ŌĆØ

The doors and building services are already installed for the buildingŌĆÖs reincarnation after the Games

The mezzanine will house a gym, while a large glass partition will be installed down one edge of the hall to create a library. Henderson says he would not necessarily have designed the building this way if it were not for the need to host an Olympic event. ŌĆ£It placed certain constraints on the design,ŌĆØ he says. Two massive steel trusses were needed to support the roof to allow for sightlines and camera angles, while the height of the space was determined by the need for consistent stratification of the air above the ice pad. ŌĆ£But it was the legacy use that was uppermost in our minds,ŌĆØ he says.

Another benefit of pairing the ice rink and the pool is the energy strategy which uses the excess heat generated by the compressors used to create the ice to heat the building and adjacent swimming pool.

After the Games the design team will be applying for a LEED Gold environmental rating and one of the ŌĆ£innovationŌĆØ credits theyŌĆÖll put forward is how the building is being adapted.

No comments yet