We are recording a podcast in a small room stuffed with trophies, models and sketches, the late autumn sun pouring in from a pretty, walled garden. Shadows from branches laden with crab apples dance across the walls as Edmund Fowles and Fergus Feilden outline their vision for the practice they founded just over a decade ago. Outside, sheep bleat and hens cluck â yet we are 400m from Waterloo station and Big Ben.

It is, frankly, idyllic and no surprise that Feilden Fowles had little trouble persuading staff to come back after lockdown. There cannot be many central London architectsâ studios where you can clear your head by feeding pigs or digging potatoes, or where client meetings and team lunches can happen under the trees.

Shortly after their return this summer, the practice won șĂÉ«ÏÈÉúTV Designâs coveted Architect of the Year Award (AYA). It is just five years since it was crowned Young Architect (YAYA) â a record. The judges clearly think they are set for greatness, but do Ed and Ferg, as they are known, find their heads turned by the towers looming over the animal pens or do they favour a more organic approach to growth?

As you will have gathered, the practice â widely admired by its peers for its thoughtful and sustainable architecture â shares its headquarters with Waterloo City Farm, a community project that it helped to establish with two charities: Oasis, which runs local schools, a church and a foodbank, and Jamieâs Farm, which was founded by Feildenâs brother to give city kids a taste of the country. It was looking for a London outpost and St Thomasâs Hospital offered temporary use of a strip of derelict land across the road from the A&E department. The charities were grateful but a bit stumped. Step forward Jamieâs brother, who drew up a masterplan for the site.

âIt reached the point where we were putting a lot of time and effort into trying to help them with some ideas and we also werenât being paid for any of it,â recalls Feilden. âSo we tried to find a way that would mutually benefit them and us.â

The practice proposed coming in as a joint partner, building its studio on the site and supporting the charities with desk space, fundraising and overseeing the rest of the buildings. Such an approach exemplifies the type of entrepreneurial spirit found in many of todayâs more interesting practices.

Edmund Fowles

Following his studies at Cambridge and the Architectural Association, Edmund Fowles gained professional experience at Hopkins Architects, where he worked on Yale Universityâs School of Forestry and Environmental Studies.

At Feilden Fowles he has delivered a range of award-winning projects, from the practiceâs own studio at Waterloo City Farm to Charlie Bighamâs food production campus in Somerset. He is currently in charge of a number of education projects, including the new dining hall for Homerton College, Cambridge, and new graduate accommodation and student facilities for Green Templeton College, Oxford. He is also leading Feilden Fowlesâ proposals for the Natural History Museumâs urban nature project.

Fowles has taught and lectured at the RIBA, the University of Cambridge, the Architectural Association and London Metropolitan University, where he taught a design studio with associate Ingrid Petit from 2015 to 2018, exploring new forms of education design.

He is also a keen cyclist and is championing the practiceâs net zero initiative.

It was also an âan amazing opportunity to design our own studioâ which helped the directors to develop their âlow techâ philosophy concerning structures, materials, craft and carbon. âThereâs nothing like paying for your own building to force you to be incredibly lean and efficient,â smiles Fowles.

The animal pens came first, followed by the studio at the western end and a large barn for community events at the eastern. All three were built by a former employee from UK-grown Douglas fir and designed in the same way, the difference being the level of refinement.

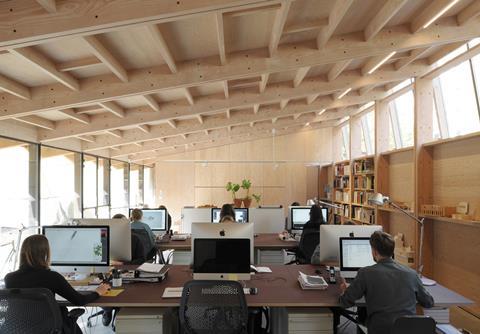

The studio, sited on the northern perimeter so it could enclose as much garden as possible, has a jointed timber frame held together by stainless steel pins and flitch plates, unpainted plywood walls and a monopitch roof tilted from the north lights to the fully glazed southern facade.

It has all been designed to be dismantled when the lease comes to an end in a couple of years. The site, along with a much larger parcel of land currently occupied by remarkable modernist flats, Ernst & Youngâs old offices, some artistsâ studios and a tangle of elevated train tracks, is part of a controversial redevelopment dreamt up by the hospital.

Fergus Feilden

Fergus Feilden, who studied at Cambridge and the Royal College of Art, is passionate about landscape, land management and how the practiceâs low-tech approach resonates and responds to current environmental themes.

He loves working with clients to create shared visions, convincing stakeholders of the impact of challenging projects. Feilden particularly enjoys working on sensitive sites and unlocking tectonically complex briefs. He recently led on The Fratry at Carlisle cathedral and on The Weston, a new gallery and visitor centre at Yorkshire Sculpture Park, which was shortlisted for the Stirling Prize in 2019.

Feilden focuses on the education, culture and heritage sectors, with current commissions including the National Railway Museum in York. He is a visiting professor at Sheffieldâs school of architecture and is a visiting lecturer and critic around the UK.

He has also sat on the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park quality review panel and judged the RIBA awards.

It has been masterplanned by AHMM and will feature labs, office space and housing designed with Piercy & Company, Henley Halebrown, Morris & Co and Cobe Architects. Feilden Fowles has a small role turning railway arches into workspace and is hoping its involvement might provide a chance to rehouse some of the charitable work as well as potentially their team. Meanwhile the firm is planning to move the existing office structure down to the West Country to become the practiceâs first satellite studio.

Award-winning projects

Which brings us back to the question of expansion. Within a decade the firm has grown its staff from two to a steady 20 and outgrown the private resi work that most architects start with. (No loft extensions for Feilden and Fowles â their first project was a ÂŁ270,000 passive longhouse, Ty Pren, near Brecon, which they designed and helped build while doing their part IIs at the RCA and AA respectively.)

More recent projects that helped to win them Architect of the Year were Yorkshire Sculpture Parkâs Stirling Prize-shortlisted Weston visitor centre, Carlisle cathedralâs Fratry extension, Yorkâs National Railway Museum and the Natural History Museumâs urban nature project, all either completed or in train. They have a dining hall for Homerton College, Cambridge, on site and are in talks with the UK manufacturer of a hydrogen-powered car about designing the âgreenest car factory in the worldâ.

So, how did two guys still in their thirties get here, and just how big are their ambitions?

Britainâs brightest

The pair met as undergraduates at Cambridge in 2002 and began collaborating almost immediately. After his part I, Fowles got a job at Hopkins, while Feilden worked at Haworth Tompkins and Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios, the practice co-founded by his late father, Richard. They continued to work together in their spare time, and the crisply detailed Ty Pren, clad in local larch and emitting just 6kg of carbon dioxide a year, caught the eye of the press. The two found themselves in an Observer article headlined âMeet Britainâs brightest young architectsâ, which led to more commissions, especially from rural clients with an interest in sustainability.

They were nonetheless âdesperateâ to get away from private homes and, just a year after setting up the practice, managed to break into education. Feilden had gone back to his school, a comprehensive in Bath, to talk staff into setting up a programme to diversify the appeal of architecture. At the end of the meeting they asked what he would do with their site, and he walked away with a ÂŁ6,000 masterplan which has slowly blossomed into a number of buildings.

âSuddenly we were not just domestic architects but education architects, which allowed us to branch out into other educational sectors,â says Fowles. âBut that was all part of a quite carefully crafted business plan that we continue to update.â

The pair have a confidence that appeals to clients, and did so even when they were still showing student projects and âbeing a bit ambiguous about themâ. It spurred them to hire their first member of staff before they were full-time or fully qualified themselves. It also allows them to turn down work that does not fit with the social and environmental values they set out right at the dawn of the practice. Feilden estimates that they pass up 70% to 80% of projects that come their way â although that includes invited competitions and shortlists.

They are in a fortunate position now where their cultural projects are of sufficient size to fund the things that interest them. But to boost revenue in the past they did office fit-outs for firms they felt shared their values. And in 2015 they landed their biggest break â designing Charlie Bighamâs ÂŁ20m, 8,000mÂČ food production plant in Somerset. That was a seismic step up in scale, and in fact it was the fees from that job which allowed them to fund the studio that has proved such a calling card.

Would a tower, perhaps down the road in Vauxhall, be beyond the pale? âWith all projects, we do quite a thorough evaluation of what the benefits are,â replies Feilden. âSo we would look at the environmental benefits and challenges, as well as the social and architectural. But if they didnât have any aspirations environmentally to be achieving something that we could all be associated with, then we would definitely turn it down. Itâs not the commercial drivers that are influencing the evolution of the practice.â

Motivations

They want to keep designing public buildings and are aiming for more than half their projects to be net zero. The practice recently achieved UK Green șĂÉ«ÏÈÉúTV Council accreditation for net zero operational carbon. âWe felt we canât possibly offer our clients net zero projects without truly understanding what that means for ourselves,â says Fowles.

We have developed a reputation around what we do best, and therefore the type of work that comes to us is more suited to the practice and where we can add value

Fergus Feilden

There are âa tonâ of other things they and their staff want to do, including research into sustainable materials, outreach in schools and offering placements to youngsters from nonâtraditional backgrounds. âThe only way we can support that is by being a viable business, by probably growing a little bit more, doing projects that are profitable and then being able to channel that surplus into doing interesting things,â says Fowles.

âThatâs partly what motivates us to grow. The values have always been really important to us and really driven us. It is the projects and the impact we can have with them that excites us, rather than trying to be a practice of 100 people.â

There is talk of a northern office, where many of their cultural projects are, as well as one near Bath, but they have no particular timescale in mind. âIf the projects didnât support it, we wouldnât grow for the sake of it. We certainly donât want to take on larger commercial jobs just to feed the practice,â agrees Feilden.

âHow lovely to be in a world where you can turn down 70% of opportunities,â remarks the director of a younger practice with a mix of jealousy and admiration. âWe are not in that world and I donât think most architecture practices are.â

There are different facets to an ethical approach, adds the director, from the hours you demand of your staff to the sustainability of your designs. All can pull you in different directions â for instance, if you work mostly for small charities they may simply not have the budgets or experience to commission, say, highly crafted buildings.

Reputation

Feilden concedes that a bit of luck has been involved but is adamant that the fact they are broadly on the path they set out to be on is mostly down to their refusal to deviate. âWe have developed a reputation around what we do best, and therefore the type of work that comes to us is more suited to the practice and where we can add value,â he says.

I think they are great architects and they seem to be great business people as well. There is often a disconnect between the two

Richard Gattiâs assessment of Feilden and Fowles

It is not just clients who are charmed by Feilden Fowles. They appear on many architectsâ mental âmost admiredâ lists, including that of recent YAYA winners Gatti Routh Rhodes.

âI think they are great architects and they seem to be great business people as well,â says co-founding director Richard Gatti. âThereâs often a disconnect between the two, with the people who are good at architecture not necessarily the people who are good at winning work or running practices.â

The problem can be traced back to architectural education, he says, which focuses on design to the exclusion of almost anything practical. It is notable that Feilden Fowlesâ third employee was a modelmaker â a crucial part of business development â and shortly after that they hired an office manager to free them from admin.

Who are their own heroes? When they started out it was past YAYA winners, but they have outgrown that. Is it now the likes of Foster and Herzog de Meuron, who consistently top the most-admired list in the World Architecture 100?

Feilden says: âWeâre always looking to others but weâve never found a practice who are our pin-ups.â He adds quickly: âThatâs not to criticise other practices â there are elements of so many that are wonderful.

âSome of the sector-specific practices know their client base and have a really good culture â some of the housing architects, for example. But other practices have a profile that we find more attractive. Thereâs all sorts of nuances or specialisms that we draw from other practices, but we certainly arenât following the path of one other practice.â

Ed and Fergâs determination to plough their own furrow will only add to their allure, and it seems certain that they will remain architects to watch. They might have a plan but, just like the seeds sown in the planters outside, no one can predict exactly what the harvest will bring.

șĂÉ«ÏÈÉúTV Talks Net Zero podcasts

Listen to Edmund and Fergus as part of our podcast series on our website via the player above or below and find all șĂÉ«ÏÈÉúTV Talks Net Zero episodes at

No comments yet