Those behind ManchesterŌĆÖs Factory International hope that the space, technology and flexibility of this megaŌĆævenue will encourage artists and performers to push the boundaries of performance ŌĆō as the designers and engineers themselves have done. Thomas Lane reports

The word ŌĆ£factoryŌĆØ has a double meaning in Manchester. It encapsulates both the cityŌĆÖs industrial past and its reinvention as a vibrant, modern destination.

The modern connection began with Tony Wilson, who founded the independent Factory Records music label in 1978 when the city was down on its luck. Factory Records brought us bands including Joy Division, New Order and the Happy Mondays as well as the legendary Ha├¦ienda nightclub. Together they helped to put the city on the map and were a key factor in kick-starting its regeneration.

The term ŌĆ£factoryŌĆØ is still firmly embedded as a key part of the cityŌĆÖs cultural terminology, despite the label going bust 30 years ago. The name is now being applied to what is described as a new global destination for music, culture and the arts. Called Factory International, this venture is a huge multipurpose entertainment venue being built on the site of the old Granada TV studios in the St JohnŌĆÖs area of the city.

The big challenge is the acoustics. A concert can generate the same noise levels as a jumbo jet taking off

Tim Laycock, project lead, Manchester council

Designed by Dutch architectural practice OMA, the venue aims to push the boundaries of performance to new heights by providing artists with an extraordinary sequence of spaces that can be configured in multiple ways. The building includes a 1,600-seat theatre with seats that can be retracted at stalls level to create a large, open space. What elevates this building above the ordinary is a huge space called the warehouse which is 21m high, 65m long and 33m wide with a capacity of 5,000 people.

Huge, movable internal partitions enable the building to be subdivided in a variety of ways. The theatre, which sits to the south end of the warehouse, has two proscenium doors separating it from the warehouse and allowing the two spaces to be used simultaneously for different events.

The warehouse also features two movable partitions to create two smaller spaces, enabling the building to be allowed for three different events at once. The proscenium doors can be raised to create an ultra-deep stage or all the doors raised and seats retracted to create an L-shaped performance space with a design capacity of 7,000 people.

On top of this, the building is packed with features to offer artists as much creative scope as possible. For example, there are fixing points spread across the warehouse walls each capable of supporting a load of up to one tonne.

The roof features 130 gantry cranes running on rails enabling equipment to be moved, raised and lowered anywhere in the space. And each roof bay is capable of supporting a technical rigging load of up to 10 tonnes.

First impressions of the warehouse are the grand scale, particularly its height, which is much greater than most performance spaces. But to call it a warehouse is to underestimate the hugely complex engineering behind this project, including demanding acoustic requirements and the need to create a large, flat performance space with a road and historic railway arches in the way.

This complexity, coupled with construction price inflation, is the reason why the original budget of ┬Ż110m, set in 2016, has spiralled to nearly ┬Ż211m. The 2019 opening date has been pushed back to summer next year.

ŌĆ£The big challenge is the acoustics,ŌĆØ explains Tim Laycock, project lead for Manchester council, which is behind the scheme. ŌĆ£A concert can generate the same noise levels as a jumbo jet taking off, so weŌĆÖve got planning constraints that say people with an open window lying on their bed in the evening arenŌĆÖt supposed to hear a thing. That has dictated a lot of the technical detail.ŌĆØ

This onerous planning requirement meant a range of noise mitigation strategies had to be employed. The theatre and warehouse both feature box-within-a-box construction where the inner box, which forms the internal space, is acoustically isolated from the outer structure. The second strand to this strategy is the use of heavyweight materials in order to dampen low-frequency noise.

The building exterior and roof are clad with precast 200mm-thick concrete panels which are isolated from the steel frame with acoustic bearings. The inner box to the warehouse is clad with 300mm-thick precast panels to the walls and a 500mm-thick slab constructed from 350mm-thick prestressed precast hollowcore planks with a 220mm-thick concrete topping.

The floor section bridging over a road uses 700mm-deep prestressed bridge beams up to 19m long with a 270m-deep insitu topping, taking the depth of this section of the slab to over a metre. More than 2,500 individually designed acoustic bearing assemblies were needed to isolate the steel frame from the precast panels alone. The inner box to the theatre is constructed from CLT.

Additionally, a 300mmŌĆō420mm layer of insulation further deadens noise on the outer part of the structure, with another 300mm of insulation applied to the building interior. Internally, this is covered with slatted boards to the theatre and fabric in the warehouse.

Multi-use space

The ability to use different parts of the building simultaneously ŌĆō say, for a rock concert in the warehouse and a poetry reading in the theatre ŌĆō means these spaces must be acoustically isolated from each other, too. This is done through the two proscenium doors, weighing 62 and 84 tonnes each, that separate the spaces. Each of the two warehouse partitions are made up of 27 panels 1,200mm wide. ŌĆ£This, as far as we know, is the largest moveable wall in the world,ŌĆØ says Lee Taylor, partner at Ryder Architecture, the executive architect on the job.

The site is located on ManchesterŌĆÖs Water Street, and the footprint includes the road itself as well as a set of historic railway arches dating from 1830. The performance spaces have been elevated by 8m in order to clear the railway arches and road, with free space underneath used for the building foyer and an external performance area.

>>Also read: The skinniest skyscraper: 111 West 57th Street

>>Also read: Things can only get hotter ŌĆō so we must tackle overheating in buildings

Two 40-tonne lifts, each capable of elevating an articulated lorry, have been built to enable props to be brought up easily to the performance level. The performance-level exit aligns with the gap between the warehouse partition walls, enabling the space on one side of the partition walls to be set up while the other side is in use.

Because the lorries can travel up and down the entire performance floor level, the slab has been designed to take a load of 1.5 tonnes per square metre. The frame also is taking the weight of the heavy roof and wall structure.

ŌĆ£The heavy floor and roof and the requirement to move a lot of heavy equipment around, plus the people up there, demands a lot of the structure,ŌĆØ explains John Edgell, structural engineer at Buro Happold. ŌĆ£When you couple that with the elevated site, you have got a really interesting structural issue to resolve.ŌĆØ

Any discussion about steel frame elements is prefixed by the word ŌĆ£megaŌĆØ because of the huge loads involved. So, there are mega-walls and mega-columns rather than plain old walls and columns. The west mega-wall forms the west side of the warehouse and the proscenium arch between the warehouse and theatre, and partially supports both roofs and the warehouse floor slab. The void occupied by the arch, coupled with the fact that a large part of the west mega-wall spans over the road, meant there was very limited space for the supporting columns. ŌĆ£You have only got two places along that line where the structure can reach down without hitting the road,ŌĆØ explains Edgell.

Those two places are at either end of the wall, so a way had to be found to introduce a third column. This column, which supports one side of the proscenium arch, terminates above the road with the loads transferred to the side by a 6m-long cantilever, nicknamed the mega-pig because of its shape. This is supported by two columns situated away from the road.

The east mega-wall is located well away from the road, so it was much easier to ground the four columns supporting it. The most southerly mega-column on this wall sits over the historic railway arches, with a redundant stairwell used for the column. The south wall is not subjected to the same loads as the east and west mega-walls, so conventional columns have been punched through the crowns of two arches and are supported on mini-piles due to the limited headroom for a piling rig

Controlling the costs

Factory International has been a long time in the making. It was announced in 2014 by then chancellor George Osborne as part of his Northern Powerhouse initiative. Planning was granted in 2017 with a ┬Ż110m budget, ┬Ż78m coming from the government and ┬Ż20m from Manchester city council, which is an enthusiastic backer of the scheme.

Costs have steadily increased, rising to ┬Ż210.8m as of October 2022. Several factors have contributed to this. Manchester council opted for management contracting as this enabled it to get to site quickly without having to spend time working up the detailed design first. This choice meant the client took the risk of cost increases, which unfortunately for the council have been significant, firstly with the impact of covid-19, then subsequent price inflation with construction prices increasing by 26.4% just since June 2021.

The unique nature of the project and the exacting acoustic requirements and structural challenges have required a level of detailing that was not fully appreciated when the project started. Flan McNamara, a hugely experienced construction professional, was brought in by Manchester council in 2020 to help get the project over the line.

McNamara, who was the construction director on Westfield White City and ran the construction of the Shard for developer Sellar, as well as working on the refurbishment of the Royal Opera House, says that Factory International is one of the most complex jobs he has ever been involved with. He sympathises with the people who did the original costing.

ŌĆ£It would have been hard to lock it [the cost] in because no one would be able to see the detail that was ultimately involved during the design process.ŌĆØ

He says virtually everything on this building has had to be designed from scratch. ŌĆ£Because of the uniqueness of this project, you canŌĆÖt get anything off the shelf. With most projects you can get stuff off the shelf,ŌĆØ he explains.

As an example, each of the 2,500 acoustic bearings between the precast panels on the building and the frame is unique, with each one taking 21 weeks to design and procure. ŌĆ£Detailing the acoustics and fire requirements has been very onerous and one of the biggest challenges here. When people are looking for simple detailing that has been used on other buildings and tested and approved, here you are developing things as you go.ŌĆØ

Changing legislation and new technology have also added to the cost. Fire safety requirements are much tougher since the Grenfell Tower tragedy, and design solutions have had to satisfy these requirements while still meeting acoustic standards.

ŌĆ£You have to satisfy both [fire and acoustic standards], which means you end up with a higher level of engineering because you default to the higher requirement. That adds complexity on site and takes longer to do, but we have never shied away from that.ŌĆØ

Theatre systems have also evolved over the projectŌĆÖs lifetime, and the specification of these has been upgraded as the project has gone along.

Despite these challenges, McNamara is confident that the building will be completed by next summer and he is immensely proud of the project and what it will do for Manchester. He praises the can-do attitude of the council and the support it has given the project team.

ŌĆ£People have no idea how great this facility will be in the future,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£It is in many ways a once-in-a-lifetime building.ŌĆØ

Structural challenge

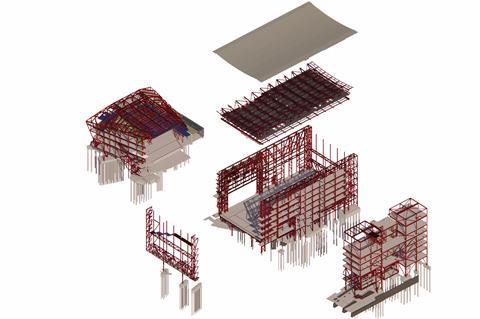

The scale of the structural elements ŌĆō the mega-columns are 2.5m┬▓ and 34m tall, and the mega-wall is 2.5m wide ŌĆō presented management contractor Laing OŌĆÖRourke with a significant construction challenge. The structure for the so-called ŌĆ£towersŌĆØ, a block on the east side of the warehouse which houses offices, plant and space for the performers, was built first along with the east mega-wall and the so-called mega-pig.

The two mega-columns forming the proscenium arch on the west mega-wall were erected as two freestanding structures. These support the 23m-long, 5m-deep, 125-tonne proscenium arch truss sitting on top of the two columns. ŌĆ£We had to stabilise the two megaŌĆæcolumns before we could hang the 125ŌĆætonne truss between them,ŌĆØ explains Lee Dawson, project engineer for Laing OŌĆÖRourke.

This stability was provided by the south truss; two roof trusses spanning between the east and west mega-walls. These were fixed together to form a box on the ground and lifted into position with a huge, 1,000-tonne Sarens crane sourced from the Netherlands. With the south truss in place, the proscenium truss ŌĆō which was also assembled on the ground ŌĆō could be lifted into position.

Edgell explains the exterior precast panels, which weigh up to 16 tonnes, presented the team with another challenge because these induce deflections into the west mega-wall. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs great having offsite precast panels, but monitoring the deflection while we put these heavy 12-tonne panels on the building and making sure we can position them in the right place was a real challenge,ŌĆØ he says.

The panels are separated by a 30mm, mastic-filled gap. The weight of the panels causes the base of the west mega-wall to deflect by up to 100mm between the mega-columns.

ItŌĆÖs great having offsite precast panels, but monitoring the deflection while we put these 12-tonne panels on the building and making sure we can position them in the right place was a real challenge

John Edgell, structural engineer, Buro Happold

Putting all the panels on with a 30mm gap would not work, as the gaps would close up at the top and open at the bottom as the mega-wall was progressively loaded, compromising the acoustic, watertightness and aesthetic requirements. The panels have been installed with a slight offset so they end up in the right place once the wall is fully loaded.

The challenge was working out the correct position for the panels. Buro Happold had to develop software that could predict how the frame would move as it was loaded and where the panels should go. ŌĆ£There are limits to the accuracy of the deflection analysis of the frame, mainly due to stiffness at connections, which is extremely hard to model accurately,ŌĆØ explains Edgell. The frame was monitored as the panels were installed and benchmarked against the predicted deflection in order to ensure that the panels ended up in the right place.

Dawson describes the panel installation as one of the more challenging aspects of the job, especially on the theatre because of its nonŌĆæorthogonal design. The walls are angled outwards from the base to the point where these meet the roof. The overhang made it impossible to position the panels using the tower crane. The angles of the walls vary around the theatre so the weight and angle that the panels need to be positioned on the building vary too.

A special lifting frame was built to correctly position the panels. This could be adjusted to get the individual angle of each panel right. The frame featured an adjustable counterbalance to keep the lifting frame level, as the panels vary in weight. The whole assembly was lifted up by the crane and the panels were positioned with millimetre accuracy.

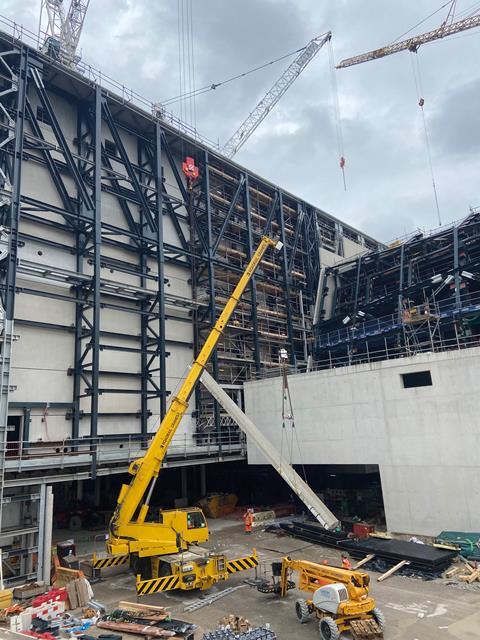

The corrugated precast concrete panels on the north warehouse wall were up to 15m long but very narrow, making positioning quite a challenge as the panels were not strong enough to be rotated from the base. The solution was to use a mobile and tower crane in tandem to lift the panels upright and then position them on the building.

Dawson says using two cranes in this way used to be illegal. ŌĆ£Luckily there was a change in the lifting regulations a couple of years ago which allowed us to do this operation,ŌĆØ he says.

The building will host a huge variety of events including exhibitions, warehouse-scale gigs, theatre and multimedia performances. It will also be the permanent home of the Manchester International Festival, which is held every two years. The idea behind the cultural venue is to allow artists and performers to experiment and push the boundaries of performance, aided by the flexibility, space and technology of the building.

Why Factory International?

A key reason for former chancellor George OsborneŌĆÖs backing of the project was that it is expected to bring 1,500 full-time jobs and add ┬Ż1.1bn to ManchesterŌĆÖs economy over the next 10 years. The council hopes it will attract 850,000 visitors a year, with 200,000 of these from outside the city.

The project has kick-started the regeneration of the

St JohnŌĆÖs creative area, which also includes the Science and Industry Museum. The council says that the creative industries are the fastest-growing sector in the city, which is a fitting tribute to the late Tony Wilson (pictured here with his partner Yvette Livesey) and Factory Records.

M&E and fit-out

With the frame and cladding complete, the team has surmounted the biggest engineering challenges. The M&E installation is well under way, with acoustically isolated plant rooms distributed around the building, and the team are busily working on the technical areas.

The fit-out is yet to start in earnest but will be relatively simple, with sealed concrete floors and exposed walls to underscore the industrial quality of the project. The sound insulation is being fixed to the walls of the warehouse and, rather than being one-dimensional, has the pattern of the steel trusses holding the building up embossed into it.

This reflects the buildingŌĆÖs industrial heritage and will hopefully give the audiences enjoying performances at the venue some sense of the extraordinary engineering that has made this building possible.

Project team

Client Manchester City Council

Concept architect OMA

Executive architect Ryder Architecture

Structural engineer and facade consultant Buro Happold

M&E engineer BDP

Cost consultant Turner & Townsend

Acoustic consultant Level Acoustics & Vibration

Management contractor Laing OŌĆÖRourke

Steelwork specialist Willliam Hare

No comments yet