The founder of the specialist contractor turned 75 over the summer. He tells Dave Rogers about nearly going under, having the gift of the gab and why he did well out of the Cardiff Millennium Stadium

John Hall remembers where he was when he told his bank manager to go and do one. His demolition business, John F Hunt, had just lost ┬Ż2m on a ┬Ż1m scheme, a strip out at a building called Park House at Finsbury Circus in the City of London.

John Hall remembers where he was when he told his bank manager to go and do one. His demolition business, John F Hunt, had just lost ┬Ż2m on a ┬Ż1m scheme, a strip out at a building called Park House at Finsbury Circus in the City of London.

He was already under special measures from NatWest, his bank at the time, who were putting the squeeze on him further. He had just won a job, a scheme to demolish Mondial House, then the main telecoms hub in central London, and he was explaining to his bank manager that he could see a way out in the next few months if only he would stand by him.

ŌĆ£I was stood on the roof of Mondial House, telling him this and he said: ŌĆśYes, IŌĆÖve heard that before.ŌĆÖ I reared up and said: ŌĆśIf thatŌĆÖs the case, I suggest you go f**k yourselfŌĆÖ. The next call was to Lloyds. I changed banks. Been with them ever since.ŌĆØ

It was a big call to sever his ties with NatWest, having had an account with them since leaving school in the 1960s.

But he reckons that, if he had not switched, he would have been finished. ŌĆ£NatWest would have wound me up.ŌĆØ

So, if NatWest thought he was too much of a risk, why did Lloyds take him on? ŌĆ£IŌĆÖm a good salesman,ŌĆØ he says with a twinkle.

But he knows how close he was to failure. ŌĆ£When I told NatWest what I told them, that was a life-defining moment. Then, I had to trust my judgement that the Lloyds guy was going to say yes and back me up.ŌĆØ

His rooftop roll of the dice was in 2006 and, several years later, John F Hunt, now well and truly out of the woods, picked up a number of demolition contracts on the Crossrail scheme around Liverpool Street.

His former bank manager ŌĆō the one who he had told to go away ŌĆō was based in Bishopsgate. ŌĆ£So the guy in Bishopsgate would have had to walk past all our sites with our name on them.ŌĆØ

John HallŌĆÖs connections with John F Hunt

Hall, who turned 75 in July, has been in charge of John F Hunt since 1982, when he set it up with a ┬Ż5,000 overdraft and started working out of his front room, with nothing more than a Volvo estate, a telephone and heaps of chutzpah.

ŌĆ£I used to work from home,ŌĆØ he says, noting the irony given the way working practices have changed since the pandemic. He had the Yellow Pages, a telephone directory and directory enquiries.

I used to tear the planning notices off the office blocks to get the information [about upcoming work]. IŌĆÖd be on the phone cold selling

ŌĆ£I used to drive into the City on a Saturday morning and tear the planning notices off the office blocks to get the information [about upcoming work]. Monday morning, IŌĆÖd be on the phone cold selling, asking if they wanted us to do some work. If you can make them giggle, youŌĆÖve got them.ŌĆØ

His very first job was a ┬Ż118,000 contract to demolish a chemical factory in Ilford, east London. His first in the City was at 18-20 St Andrew Street, in the heart of LondonŌĆÖs legal district.

It was around 1988 and he later found out that he had won it by ┬Ż400. He was appointed to the work by Davis Langdon & Everest ŌĆō which he acknowledges was a feather in his cap and a good selling point for future deals.

He admits he can talk and he got his gift for the gab from his time at an engineering company in Dagenham, called Jefferies Engineers. This was in the mid 1970s.

ŌĆ£It was run by two brothers who were constantly at each otherŌĆÖs throats,ŌĆØ he recalls. The business happened to be on the same industrial estate that the forerunner to todayŌĆÖs John F Hunt ŌĆō John F Hunt Ironworks ŌĆō was located.

Hall describes one of the brothers, Ben Jefferies, as something close to a business guru. ŌĆ£He was a real character. Six foot two, he would shout and scream like no tomorrow. He could tell a joke about any subject.

He taught me how to wheel and deal like no tomorrow. It was a serious education

ŌĆ£He used to sit me down every Monday morning and teach me how to buy. He taught me how to wheel and deal like no tomorrow. It was a serious education. Bid for everything, always haggle.

ŌĆ£I was there for one year before he sacked me, which was twice as long as the three previous works managers. Looking back, he was a mentor in a way.ŌĆØ

A few years and few jobs later, he started John F Hunt after John F Hunt Ironworks went bust. He kept the name because it was well known and well regarded. He called it John F Hunt Demolition.

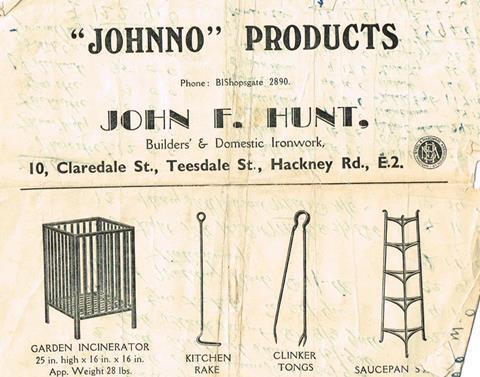

The original John F Hunt ŌĆō the F stands for Frederick ŌĆō had been set up in the 1930s as Joseph Hunt & Sons. HallŌĆÖs grandfather, John F Hunt, took it over just after the war and renamed it John F Hunt Ironworks.

ŌĆ£He was a seriously formidable character,ŌĆØ Hall says. ŌĆ£He would eat six boiled eggs for breakfast.ŌĆØ He went on to have two children, John and Elizabeth. ŌĆ£My father [Alan] married Elizabeth,ŌĆØ Hall explains.

Formative years

Hall remembers being driven down in an old Commer van to the East End of London from the age of 10 ŌĆō ŌĆ£the winters were freezing cold, I used to hate it. IŌĆÖd have to get out of bed and be in Shadwell by 7 30; the guys would rub Swarfega on my faceŌĆØ ŌĆō but he was determined not to join the family business.

He wanted to experience a life outside Hunt and so began a career away from the firm. As well as Jefferies, he worked for container firms and steelwork firms, including one, London Containers, which he credits with teaching him how to estimate.

He watched and learnt and, by 1982, as the country was still in the teeth of a recession, he launched the new-look John F Hunt.

He had done a diploma in engineering at technical college and admits that, if his grades had been good enough, he would have gone to Aston or Brunel universities to study engineering. But they werenŌĆÖt.

How John F Hunt started

1930s John F Hunt began life as a blacksmithŌĆÖs business in Hackney, east London, called Joseph Hunt & Sons.

1945-49 Jospeh HuntŌĆÖs son ŌĆō John HallŌĆÖs grandfather ŌĆō a blacksmith, changes the name to John F Hunt Ironworks. The F stands for Frederick. John HallŌĆÖs father Alan marries HuntŌĆÖs daughter Elizabeth and joins the firm from the air force.

1949 John Hall is born.

1980 After working for several companies, including Jefferies Engineers, London Containers and Sheffield-based steel and engineering firm TW Ward, Hall joins the family business.

1982 John F Hunt Ironworks goes bust. In September that year, Hall sets up a new business called John F Hunt Demolition, having ignored the advice of his mother to call the firm John Hall Demolition

ŌĆ£At college, I was chairman of the dance committee and captain of the rugby team. I just went there and enjoyed myself.ŌĆØ

It was at one of these firms that he first chanced upon demolition. ŌĆ£The firm I was with had got into industrial dismantling, the demolition of heavy industrial structures ŌĆō power stations, gas works, steel works. A guy there said, ŌĆśyouŌĆÖve never seen as much money as long as you liveŌĆÖ.ŌĆØ

He says two jobs made his business. The first was helping to write guidance notes for the National Federation of Demolition Contractors on how to bring down tower blocks over 10 storeys, mainly the 1960s ones owned and managed by local authorities.

The second was Cardiff. Mere mention of that name, for older heads at least, can mean only one thing: the Millennium Stadium.

The job was the best-known of the several that eventually felled Laing Construction, then ŌĆō along with Sir Robert McAlpine ŌĆō the blue-chip name in contracting.

While Cardiff was helping to send Laing under, Hall says the scheme went well for his business. ŌĆ£We did OK on CardiffŌĆ”ŌĆØ

He was carrying out demolition work on the old ground to make way for the new one. His bit was going well but he remembers the wider team had miscalculated on the roof and other structural issues.

Still, he has kind words for those who worked on it. ŌĆ£The Cardiff team were on it, really driven to get the job done, a real good bunch of guys.ŌĆØ

But he could see that things were going wrong and it was at a corporate shoot that it dawned on him how bleak things really were at Laing.

ŌĆ£We were on a table and a very senior guy from Laing was there. He told us Cardiff and the NPL [another loss-making job called the National Physical Laboratory] were just the tip of the iceberg. He was completely demoralised and just opened up.

Every tower crane needs a generator and thatŌĆÖs what kicked off the power business

ŌĆ£He said they werenŌĆÖt coming back from it all. Everyone went quiet and we all thought, ŌĆśChrist, thatŌĆÖs it, theyŌĆÖre finishedŌĆÖ.ŌĆØ

At the same time as Cardiff, he admits he was getting ŌĆ£beaten upŌĆØ on the job to turn the former Daily Mirror building at the bottom of Fleet Street into a new headquarters for SainsburyŌĆÖs. Getting the printing presses out of the four-storey basement required dismantling kit at ground level and reassembling it in the bowels of the building below.

ŌĆ£Everyone thought we were doing badly on Cardiff and really well on the Daily Mirror. It was completely the reverse.ŌĆØ

After Cardiff, the firm eventually moved away from being demolition only and into pouring concrete and setting up a power business in 1998, which turned over close to ┬Ż50m last year. ŌĆ£Every tower crane needs a generator and thatŌĆÖs what kicked off the power business.ŌĆØ

Hall says his lowest point was nearly going under on the Park House scheme. He admits he took a risk. ŌĆ£Work had dipped and we needed a job. We took it on.ŌĆØ

He adds: ŌĆ£On Park House, I made a call. If youŌĆÖre going to run a business, the term is putting your head on the block. Most of the time you get it right.

ŌĆ£I took a gamble on a job many, many years ago on the ground remediation. The client said ŌĆśare you happy with the figureŌĆÖ, because it was on us if it was wrong. I added ┬Ż250,000 [to the contract price] and I spent ┬Ż50,000. That was in 1993. I made the right shout.ŌĆØ

Running the business today

Hall says the firm typically carries between 5% and 10% problem jobs. ŌĆ£You canŌĆÖt budget for that,ŌĆØ he adds. ŌĆ£No contractor can say all his jobs are on song and making money.

ŌĆ£Every now and again we will get it wrong. If you win a lovely job, I sometimes ask myself: why have I won it, have I cocked up?ŌĆØ

Of course, muck up on a job and firms can quickly get into a heap of trouble. The industryŌĆÖs low margins have not helped, although Hunt last year posted group-wide margins of 6% pre-tax.

But the differences between its companies are stark ŌĆō its power business racked up an eye-wateringly good 11.5%, ground remediation 8% but its London contracting arm was in the more familiar territory of 2.4%.

I think too many clients underestimate the benefits of negotiation, building trust and a personal relationship with the contractor

He says: ŌĆ£I think too many clients underestimate the benefits of negotiation, building trust and a personal relationship with the contractor, and indeed allowing them to make a fair and reasonable margin for the effort they have put in.ŌĆØ

When he started, Hall says, margins were 15%. ŌĆ£Now weŌĆÖre doing well [in London] if itŌĆÖs 3%.ŌĆØ

From ┬Ż5,000 overdraft to ┬Ż220m business

John F HuntŌĆÖs chairman has a philosophy for business. ŌĆ£Never be afraid,ŌĆØ John Hall says, ŌĆ£to employ someone smarter or more intelligent than yourself. ThatŌĆÖs the secret.ŌĆØ

After several years of eschewing the family ironworks business, one he says that used to make the cookers for the first Chinese restaurants that started to spring up in London, he finally joined the firm in 1980.

He wanted to broaden his horizons first, do his own thing. In 1982, John F Hunt Ironworks hit the skids and that September he set up the John F Hunt of today. His mother wanted him to call it John Hall Demolition, but he stuck with the old name.

ŌĆ£John F Hunt had a good name and I would leverage off their contacts.ŌĆØ These included Mobil Oil and other firms based at the former Coryton oil refinery in Essex.

There are now 21 operational businesses within the wider John F Hunt group, working in sectors such as demolition, structures, rail and asbestos removal. Other businesses include workwear and a golf course it owns at South Ockendon in Essex.

Turnover is expected to be between ┬Ż210m and ┬Ż220m this year. In the 12 months to March 2023, its last set of accounts filed at Companies House, the firm posted a revenue of ┬Ż206m and a pre-tax profit of ┬Ż15.5m.

Memorable schemes include the Millennium Stadium in Cardiff and a job in the mid-1990s to pull down the old MI5 building on Curzon Street for Development Securities. ŌĆ£The ground floor slab was 10ft thick. It was a bomb-proof bunker, basically. It was a challenge.ŌĆØ

He adds: ŌĆ£I am really proud of the London business for the reputation and traction we have gained, in a relatively short period of time, to self deliver concrete structures. My background has always been breaking the stuff out and I never in a lifetime dreamed that we would one day be digging and constructing deep basements and pouring the likes of a 23-storey core.ŌĆØ

Of all the changes Hall has seen over the years, the biggest has been in health and safety. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs improved immeasurably. The difference is beyond comparison.ŌĆØ

There is one constant, though. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs lovely when you build up a relationship. You donŌĆÖt want to lose that, the relationship is personal to you. ItŌĆÖs a lovely thing. The buzz you get from it.

ŌĆ£Every now and again, you pull a rabbit out of the hat. YouŌĆÖve met someone a few years ago and they say, ŌĆśI remember you from so and so, letŌĆÖs talkŌĆÖ.ŌĆØ

He says the big change between then and now is one thing: overheads. ŌĆ£Our overheads are colossal,ŌĆØ he admits. ŌĆ£We have a lot of people [the company has around 850 staff] and there is a shortage of good people. The people you employ, you end up paying them big salaries.

ŌĆ£London, especially, is very competitive. ItŌĆÖs the biggest market but very competitive. London is where the money is, but itŌĆÖs very tough, clients and consultants trying to sell you a dream ticket. To get a share of it, you go through the wringer. You need a big team to support every aspect of the business to earn a margin.ŌĆØ

He nearly retired a decade ago but a management buyout [MBO] went wrong and he is still in the firmŌĆÖs office at Grays in Essex three days a week, the other two working from his home also in Essex.

He is wealthy enough to never have to work again, so why keep on keeping on? ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs in your blood, isnŌĆÖt it? I enjoy meeting people, having a few lunches. I take it very seriously. ItŌĆÖs a bit of a passion, I suppose.ŌĆØ

That passion could have been tested with the recent investigation by the Competition and Markets Authority which saw John F Hunt and nine others in the demolition sector fined a collective ┬Ż60m for bid-rigging. Half of the 10 ŌĆō although not Hunt ŌĆō were also found to have made so-called ŌĆ£compensation paymentsŌĆØ.

Straight to the point, then. Was it a fair cop? Hall says it was. The firm moved quickly to pay its fine, ┬Ż5.6m, and Hall adds: ŌĆ£I think we got benefit out of coming clean.

ŌĆ£We had the cash [to pay the fine]. Pinsent Masons [the law firm acting for Hunt on the CMA case] said, ŌĆśdonŌĆÖt try and be clever, pay the fineŌĆÖ. We paid up, got it off the books and moved on.ŌĆØ

If the right offer came along to get me out, I would listen to it

That was 18 months ago and Hall says he is pleased the firmŌĆÖs reputation has survived intact. ŌĆ£Being a solid, blue-chip contractor ŌĆō IŌĆÖm proud of that.ŌĆØ

He admits, at 75, that he would consider offers about selling his stake in the firm, which stands at 90%. ŌĆ£If the right offer came along to get me out, I would listen to it.

ŌĆ£Either an MBO or an EOT [employee ownership trust]. It would give the young guys a chance, and you need to incentivise the younger generation.ŌĆØ

But it is not just about the younger generation for Hall; long-servers are looked after, too. Those who have been with the business 20 years are handed a Cartier watch to celebrate. ŌĆ£We think itŌĆÖs a nice thing to do.ŌĆØ

He adds that the firm has had offers for parts of the business ŌĆō there was a ŌĆ£seriousŌĆØ approach for the power division last year, but it came to nothing ŌĆō and admits selling some parts of the business, contracting notably, would be harder than others.

Still, it feels that the only way Hall would leave John F Hunt is in a box. ŌĆ£As long as IŌĆÖm smart enough, compos mentis enough, can add value to the business, I will stay ŌĆō even if itŌĆÖs a nominal chairman role.ŌĆØ

He seems sometimes bewildered that his ┬Ż5,000 overdraft back in 1982 has turned into a business that is predicted to see income this year hit ┬Ż220m. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs just snuck up on me,ŌĆØ he says, slightly baffled. ŌĆ£To my mind, itŌĆÖs still the same company I started all those years ago. ItŌĆÖs just a bit bigger.ŌĆØ

Shooting the breeze and swimming with the fishes

Although born in Stratford and raised in Leytonstone, John Hall is that rare East End beast: heŌĆÖs not really a football fan, so a life-long association to West Ham United has passed him by.

Rugby is more his game, but his real passions are shooting and diving. He has been shooting for years and it tends to be partridge and pheasant, mainly at Exmoor in the West Country, some times in Hertfordshire, while he can also be found traipsing the moors of North Yorkshire.

He shoots for fun as well as a charity called the Birdshot Uveitis Society, which, the charityŌĆÖs website says, ŌĆ£is a rare hard-to-treat, auto-immune, eye condition called birdshot chorioretinopathy or birdshot retinochoroidopathy, also known as birdshot uveitisŌĆØ.

It is called birdshot because of the black spots sufferers get in their vision. Hall has been living with it since he was 50 and at first thought he was going to go blind.

He canŌĆÖt be sure but he thinks it all started with some poorly cooked shellfish while holidaying in France. ŌĆ£Who cooked it? Me.ŌĆØ

He says he thinks he picked up a virus from some underdone shrimps. ŌĆ£Within days, I was in bed.ŌĆØ

His immune system killed off the virus, eventually but, in the words of Hall, it ŌĆ£went looking for something else and started killing off my eyesŌĆØ. He is partially blind in his left eye ŌĆō his right is fine ŌĆō and has an injection to keep things under control every other week.

He found out about the charity after Googling Birdshot. ŌĆ£My hobby is shooting birds. The charity is called Birdshot,ŌĆØ he deadpans.

As well as shooting, he is a serious diver, having discovered the activity while on holiday in Antigua. Not one for reading on the beach, he spotted a diving school, wandered along to find out what it was all about and has been diving ever since.

He owns a place in the Egyptian resort of Sharm El Sheik and goes diving in the Red Sea, which is on his doorstep.

ŌĆ£The adrenaline you get from it is incredible,ŌĆØ he says. He has been sucked down by cyclones and unnerved by Oceanic Whitetip sharks in Sharm El Sheik, after a boat near to where he was diving began feeding them bait.

A couple of weeks later, in December 2010, there was a fatal attack at the resort ŌĆō widely believed to have been caused by a Whitetip ŌĆō leading the resort to be dubbed Sharm El Shark by the tabloids.

But the one time he came closest to a serious incident was rather more humdrum. Depending on the sort of diving, divers can take two types of oxygen down with them ŌĆō a low mix and a 100%, high-mix depending on the depth of the dive. The lower mix is used at depths below 6m because of water pressure.

One day, he went to take a glug from the wrong cylinder ŌĆō the 100% one. ŌĆ£I would have spit the regulator [the device that goes into the mouth] out, convulsed and drowned.ŌĆØ

He was saved by a sharp-eyed instructor who alerted him to the fact he was about to take a slug from the wrong cylinder. ŌĆ£It would have been curtains,ŌĆØ he admits. ŌĆ£A few days later, I did the same dive, no problems.ŌĆØ

1 Readers' comment