New London CEO talks about her vision for the future, the allegations that threatened to bring the practice down, and the resilience that she says helped it survive

What happens when accusations of egregious wrongdoing hit the founder and globally recognised face of a leading architectural practice? This is not a hypothetical question on a management course, but the real-word scenario that last summer seemed on the verge of destroying David Adjaye’s career and bringing down the hugely successful practice he founded.

When the Financial Times’ story alleging abusive and professionally inappropriate behaviour with three black women broke on 4 July, it triggered a wave of clients from Liverpool to the UAE to drop Adjaye Associates. Adjaye himself acknowledged relationships with three women whom he went on to employ, but said they were consensual and that key abusive and coercive incidents set out in the article had simply not taken place.

The FT says the version of events it reported was corroborated by the women’s colleagues, friends and families, and that it spoke to 13 members of staff, some of whom referred to “toxic” working hours within the firm. While many clients did stand by Adjaye, the business was forced to cut staff and retrench in order to manage the financial impact.

One of the people at the forefront of managing the practice‚Äôs response was Lucy Tilley, a longstanding and trusted colleague of Adjaye‚Äôs. She has been a central ‚Äì but previously low-profile ‚Äì figure in the practice‚Äôs evolution. She has rarely spoken to the press but agreed to speak to ∫√…´œ»…˙TV Design, ∫√…´œ»…˙TV‚Äôs sister title, to address the allegations and set out her vision for the London studio.

Appointed earlier this year as CEO of the UK office as part of the company restructuring that followed the scandal, Tilley is taking on an increasingly outward facing role. She has been at the practice for three decades, overcoming class barriers to succeed in architecture despite the odds. Her grit and determination saw her play a key role in building a globally successful business.

Recent events have put a spotlight on how she hopes to lead Adjaye Associates towards renewed growth. But before looking ahead, BD wanted to understand how she reacted to the fallout of last year’s FT story.

She found out about the allegations two months before the storm broke, so was to some extent prepared, but the impact on the business was still significant. “It was hard because it was a great place to work,” she says. “Everyone loved it here and we were working on some of the world’s most exciting projects.”

The response from many staff was one of incredulity: “They were telling me that they didn’t recognise this ‘toxic’ workplace and that they loved it here. The staff were crying, the clients were crying. It was horrible. It’s disgraceful.”

We have many loyal clients. Our clients know David and they tell me, ‘I don’t recognise this person – we’re not going to leave’

Tilley describes how 82% of staff are from diverse backgrounds and how the practice provides opportunities to people who would not normally have access to a career in architecture. “We had to let some of them go,” she says. “It is heartbreaking.”

The business lost staff in London and New York. “You mentor those people for years. You give them an opportunity, and then someone’s just taking their jobs away from them because of a story that to me doesn’t ring true. It was really difficult, losing some incredible talent.

“The media reported all the projects that we lost, but there was no report of the projects that we kept. So I think this is an opportunity to thank all of our clients that stayed with us.

“We have many loyal clients. Our clients know David and they tell me, ‘I don’t recognise this person – we’re not going to leave’.”

The practice describes itself now as “firmly focused on the future as we go from strength to strength” and “gaining new work and recruiting in all three studios”. Adjaye Associates has confirmed to BD that regarding the allegations “there are no ongoing investigations in any jurisdiction, nor have there ever been any”.

David Adjaye also made the following statement to BD: “I am grateful to the clients and teams across our studios who have carried us through this difficult period following the baseless media allegations written about me last year. We continue to move forward and grow.

“The firm has a strong portfolio of projects under way internationally. Adjaye Associates in Accra is now firmly established and is a true global partner to our studios in London and New York.”

From a BTEC to Foster + Partners

It is a situation that few architects would anticipate having to deal with in their careers, and even fewer would feel equipped to manage. Tilley’s mix of fierce loyalty and hard-headed practicality means she was perhaps temperamentally prepared to weather such a storm. But who is the woman now heading Adjaye’s UK office?

Her working-class background is unusual in architecture. Her father was a milkman and she was the first in her family to attend university. By her own account she had little idea what career she wanted to pursue.

After turning down a school-leavers’ job at Barclays bank (her mother warned her that she would get bored), Tilley won a place on a Youth Training Scheme BTEC course that was keen to attract more women into construction. At 16 she was placed for four days a week with an architect in Islington.

“It was a tiny little practice, still drawing with pens,” she says. “That was the beginning of my career.”

The fifth day was spent in college. “We used to build brick walls. It was very practical, very much about where the damp-proof course goes.”

Two years spent in a small practice exposed Tilley to a range of work and responsibility that many architects do not experience until they are qualified, if at all. When the partner she worked for took a work trip to New Zealand, she and a young colleague were left to get on with project delivery on their own.

“He left us in charge of this practice at 16,” says Tilley. “We had to fax him in the morning that we had arrived at work. Then, throughout the day, we would go to site, delivering a nursery project, and then fax him again before we left in the evening.”

She was encouraged to apply to South Bank University to do her undergraduate degree in architecture. “And that’s where I met David,” she explains. “He was my tutor. He was a real influence on why I continued with the career – he has always pushed me.”

Tilley shared a bedroom with her sister, who she kept awake by working late into the night. In the end her mother bought her a five-foot by three-foot shed so that she could work in the garden and leave her sister in peace.

“It had no windows and was the width of my drawing board – I could hardly move,” she says. “But David would come every night to give me crits. We would pin everything up in the room and he’d be there pushing – ‘You know, you’ve got to do this’.”

On the verge of not presenting her final degree project, Tilley’s mum called Adjaye and asked for help. “So, he came, in his little banged-out Golf. And, although I remember I cried the whole way, he was saying, ‘You’re gonna be fine. You’re gonna be fine. You’re gonna do this.’

“So, he took me to uni and I presented for my degree. I got my first-class degree and I was super proud of myself. And then I went to work for David for my year out. It was Adjaye and William Russell at the time – there were three of us, two partners and myself.

After six months working in a cramped studio space on the Portobello Road, Tilley decided to accept an offer from Foster + Partners. “David said, ‘Look, we’re tiny. If you go and work for them, you can look at how people structure things properly, really get to understand how a big machine works.’ So, I went to work there for six months. I worked on the HSBC Tower in Canary Wharf. That was great just to learn the different scale.”

The Architectural Association

Tilley then won a two-thirds scholarship to the Architectural Association. “It was difficult,” she says of the AA. “I had been at a really practical school – very much about how to build buildings – and then I went to the AA and suddenly they were asking me about what my ideas were behind what I was doing. What was the philosophy?

“It was tough for a year but, by the second year, I really enjoyed it. My tutor was Shin Egashira – he was incredible, really very much about building. We went to Japan, we built a bus station, it was really practical.”

Mohsen Mostafavi was the then-chairman of the AA. “He was a really great mentor as well,” says Tilley. “Always pushing, always telling me, ‘You’re doing great’.”

A feeling of insecurity and sense of class prejudice however seems to have overshadowed much of Tilley’s time at the AA, where she developed a particular anxiety around being questioned about her background. “You know, a lot of people always ask, ‘what do your parents do?’

“I’d say, ‘My dad was a milkman’ and people were like, ‘Architecture isn’t really for you. Your dad’s a milkman – you shouldn’t be doing that’. And they’d be almost laughing at me.

“So, for many years I just tried to avoid the question. I dreaded people asking me what my parents did. I look back over my career and that’s all I’ve been judged for.

Tilley says she has lost count of the number of times that people have assumed she was not an architect. “The amount of meetings I’ve gone to and people ask, ‘Are you the office manager? Can you take my coat?’ It has been there my whole career.”

A return to Adjaye

“I finished my master’s degree and Mohsen came to my parents at the end of the year show and said, ‘We can’t let this girl go. You know she’s incredible, and she did it all in her heels.’ So, he asked if I wanted to teach at the AA, which I did. I taught there part-time for three years with Shin Egashira, which was great.

“And Mohsen was really supportive. He was pushing me in front of all of these famous architects.”

It was at this point that the possibility of returning to work for Adjaye emerged. “I remember Fosters offered me £18,000 a year and David offered me a job for £14,000. So, it was really like, ‘Where do I go?’ But, when I worked at Fosters, I didn’t really fit in. I didn’t feel at home. I felt much more at home working with David.

“I had a long chat with Mohsen and he said, ‘Go with what you feel comfortable with – if you feel comfortable working with David, then go.

“David had a couple of small residential projects, but he had just won this big penthouse in Kensington Palace Gardens. He wasn’t one of those big-name architects at the time. But he was my mentor.

“He had made me who I was at that point. So, I thought, ‘You know what, I think this journey’s going to be good’. So, I went and worked for David.”

First 10 years at Adjaye’s

Tilley describes the first decade back at Adjaye’s as “more about the architecture”. She was drawing, making models and delivering projects. “More of the stuff architects become architects for…

“Those 10 years were really all refurbishments of houses. I worked on almost all of them – Barnsbury Street, Kensington Palace Gardens, St John’s Wood – it goes on and on.

“It was a great testing ground for the larger projects that we worked on later. But what was interesting for me was that, while we were doing a lot of wealthy people’s homes, we were also being commissioned at the same time to do some social housing schemes.

“I remember David telling me, ‘You know it’s easier to build buildings when you’ve got a big budget. But the challenge is how to do something incredible for people that don’t have as much money.’ So that was really something I was interested in – how do you give the quality of air and light to people all on a tight budget.

“It took a long time for the practice to move up a scale. When you’re doing smaller-scale projects, no one trusts you with the next project up. So we had to pitch a lot, fight a lot. And then we went on to the Bernie Grant Centre, Stephen Lawrence Centre. I worked on all of those.”

Tilley has now been a director for around two decades and believes her background and experience means she took to management naturally. “I was managing from day one because I’d been doing that from 16,” she explains. “I think it was a natural instinct. I am creative, but I’ve got this weird kind of practical side to me very much about how to get it done.

“I’m not very wishy-washy. I don’t go off into a tangent into this creative world. I’m super into the creative side, but also the business side.”

The storm

The decades of experience in management appear to have prepared Tilley well for the storm that broke in July 2023. When the FT published its story, Tilley says she was angered by what she feels was a one-sided article.

“I couldn’t believe it, to be honest. I’ve known David for 30 years plus and the picture that was painted of him is nothing to do with what he is like.”

In the 2023 article Adjaye and his legal representatives were given the opportunity to respond to the allegations. The FT published this statement from his lawyer: “I am ashamed to say that I entered into relationships which, though entirely consensual, blurred the boundaries between my professional and personal lives. I am deeply sorry.

“To restore trust and accountability, I will be immediately seeking professional help in order to learn from these mistakes to ensure that they never happen again.”

Tilley similarly insists that, while relationships had existed prior to and during the women’s employment by Adjaye, they were not coercive or controlling.

The FT article stated that “a lawyer for Adjaye said that the three women each had ‘their own grievances’ against Adjaye”.

Two of the women who were based in the Ghana office were eventually dismissed from their jobs when, according to the practice, it “became apparent that their skills weren’t a good fit for the roles”. The FT’s report confirms that a $40,000 payment was made by Adjaye Associates to one of the women in May 2019, as part of a settlement. A second woman also says she received a settlement of $1,475.

The FT reported that Adjaye’s lawyer presented evidence of one of the women then later “demanding $120,000” in addition, although she claimed not to recall sending the email with the demand.

“There are two sides to a story, and I’ve seen the evidence that was given to the FT from David,” says Tilley.

“There were WhatsApp messages from after these women said that he did these things to them saying ‘merry Christmas’. It wasn’t what it was made out to be in the FT, and it’s really unfair.”

One of the women in the FT story also alleged that the Ghana office had been chaotically run, and that she had been left unpaid and short of food for herself and her child. Tilley acknowledges that, when the Ghana office was set up, it was a small entity without a clear structure. But she denies that staff went unpaid.

“People were always paid. No one would stay if they weren’t being paid.”

No legal proceedings

Tilley believes that the absence of legal proceedings speaks for itself. “There’s no legal case against him and yet somebody can just write in the media whatever they want about somebody. Shocked is an understatement. You can’t just write something about somebody and cancel somebody’s reputation by media trial.”

Although Tilley says that Adjaye considered ways to publicly address the story to restore his reputation, the view was taken that this would only feed a negative narrative. “When you’re accused of something you haven’t done, you want the world to know that you haven’t done it. You’re desperate to tell people, ‘I didn’t do that’.

“He’s not that type of person. And so, imagine how he feels, or his family feel, that he can’t give his side. It’s horrendous, to be honest. I read the newspapers now and I have to think twice about everything I read because you can’t trust what people say about each other.”

Why, then, did Adjaye not come out more openly and forcefully in public to refute the allegations? “He’s got his reasons, but what I know is that he didn’t want to start another media frenzy of him fighting back against these women.”

All three of the women who accused Adjaye were described in the FT article as self-identifying as “lighter-skinned” black women. One of the accusations made was that Adjaye had described black women as “low-hanging fruit”, singling them out for a relationship, before undermining them for not being “black enough”.

The FT article quoted Adjaye’s lawyer as stating that he “rejects entirely the overall portrayal of his conduct during their relationship, such as the claims about his attitudes towards black women and the imputation that his behaviour was ‘belittling’”.

Tilley is also adamant this is not in character. “He puts women on a pedestal. He’s always pushed me professionally, but I’ve never felt uncomfortable around him, nor have any of my staff.

“I’m a white woman, so some people might ask, ‘Well, you’re white, so what about the black women?’ There’s not one woman of colour in the office that feels uncomfortable around him. There are many men in the industry that treat women in a particular way – he’s not one of them.”

The FT report stated that the three women in its report “felt compelled to come forward about their experiences in order to prevent other women from encountering similar abuse and to make public the architect’s private behaviour”.

Tilley repeatedly points out that 82% of the practice’s staff come from a “diverse background”: “67% of our staff are black, 53% in the London office are women. And many of the staff are black women.

“I asked all the women that were here, the women of colour, ‘Have you ever felt uncomfortable?’ And they’re like, ‘Absolutely no. Far from it – that’s why we’re here.’

The impact on her team and the office was significant but navigable given that many clients stood by Adjaye and the practice. “Many more clients stayed than left,” says Tilley, “although it was way more interesting for the media to report the ones that left.

“But unfortunately, there were some incredible projects that we lost and I know it was difficult for clients. Some struggled with it. We had tears from clients. People didn’t want to leave, but they felt that the media had put them in a position where they had to.”

Adjaye has admitted that he had relationships with the three women while he was married. “That’s something he and his family need to work out,” says Tilley. “That is not part of his business. That’s something he and his wife need to sort out between them.”

Many have perceived the pattern of behaviour of relationships with female employees – even if entirely consensual – as in itself a serious lack of professional judgment. “Absolutely. Absolutely. I totally agree,” says Tilley. “But look, it’s happening in many practices.

“Yes, it is inappropriate. Yes, you shouldn’t have affairs with staff members. But, you know, that happens not just in architecture. That happens across the world. And we can all judge whether that’s inappropriate or not, but why don’t the FT write about the other architects that are doing it?

“All the architects I’ve met since this has happened ask why the media selected David.”

Is the implication that some of the response to the FT’s report relates to Adjaye being singled out for cancellation because he himself is a successful black man?

“I wasn’t going to say that. But, as a white woman, I can tell you I hadn’t witnessed racism in my life until I came here, and I can tell you for the last 30 years I’ve seen racism beyond what you can ever believe.”

Restructuring

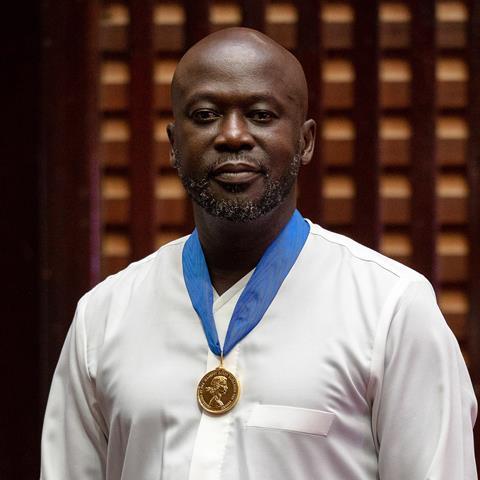

The practice has responded to the allegations and Adjaye’s recognition that the relationships were professionally inappropriate by restructuring and seeking to ensure that recruitment is handled by a panel, rather than through Adjaye making appointments directly. Tilley is CEO of the London office, while Pascale Sablan and Kofi Bio head up the New York and Ghana practices respectively.

The practice has also set up an ethics and policy committee with an independent external advisor to consider any potential grievances.

“We have monitoring of how we employ staff and who makes those decisions,” says Tilley. “We have internal boards, an ethics committee, and we’ve put procedures in place.”

Meanwhile Adjaye retains 100% ownership of the three offices, which although financially separate, share work and collaborate as a single entity. “Pascal and Kofi and I are really close. We meet two times a week and it’s run as a global practice.

“The link is David. They’re all run in the same way. We’ve all got the same ethos. We all are trying to create architecture that evokes change. We’re part of one family.

“David designs all the buildings. What we want him to do is carry on doing what he’s good at – and we will run the business.”

Tilley has played an integral role in driving the business, from a team of three to 150 staff across three offices. What does she envisage next for the practice?

“It’s definitely been a challenge. There’s been lots of bumps along the way. But that resilience makes you stronger. If I hadn’t been through what the practice has been through over the last 30 years, I wouldn’t have survived this.

“And it’s not just me, it’s the resilience of the practice – there are many people that have been here 20 years, directors, staff – it’s the whole team here.

“We’ve built up a resilience. We’ve been let down. We’ve been through tough times. We’re tough, we’ll get through it and it makes you want it even more.”

Looking to the future

“It’s an exciting time,” says Tilley, who expresses a desire to rehire staff who wish to return and get numbers back up to 200. “We’re working on some great projects. We’re obviously working on the Holocaust Memorial.

“I’ve met many of the [Holocaust] survivors and they’re getting old. They’re saying, ‘Please make this happen. Please allow this to be built before I die.’ You just want it to happen for them. I’m hopeful that it gets through, but it’s been a long journey.

“And we’re also working on a new mosque in Abu Dhabi, which follows on from the synagogue, church and mosque we did there recently. And we’ve been commissioned to design the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, which is a contemporary art museum for Indian art. It’s incredible – 100,000 square metres and it houses a lot of new contemporary Indian artists.

“We’ll work harder carrying on with our legacy, which is to create these incredible places for people, for communities, and we’ll keep going.

“I think it’s an exciting time. We feel positive. We’re focused on incredible projects with incredible people and on keeping on doing what we do, which is making architectural change, places for people. So that’s what we’re doing.”

As Adjaye Associates seeks to turn a page on this crisis, some in the profession may be looking on with continued anger, wondering if this is a case of a successful man abusing his position and leaving a series of victims to deal with their trauma.

Tilley and many of the practice’s clients are clearly convinced that Adjaye is guilty of nothing more than inappropriate behaviour – an issue that can be addressed through employment processes and for which the personal fall-out is primarily an issue for him and his own family.

A guest at the recent RIBA Royal Gold Medal celebrations for Lesley Lokko at 66 Portland Place, Adjaye also appears to be making tentative steps back into the public sphere.

As with all such allegations, it seems likely that they will continue to dog Adjaye personally, whatever happens with his business. Whether this is seen as just desserts, or a grave injustice to a man who many see as one of the world’s most innovative black creatives depends on who you choose to believe. For now, there remain those likely to require further convincing.

In the pipeline

Adjaye Associates is currently working on a wide range of projects. These include a district hospitals programme in Ghana which aims to revolutionise the country’s healthcare system by creating advanced, accessible facilities nationwide.

Each single-storey campus includes key medical services, such as surgery and maternity wards, and support structures like residences and waste management. Utilising prefabricated systems and ecologically responsive designs, the project seeks to prioritise adaptability, efficiency and sustainability.

Also in Ghana, the redesign of the WEB Du Bois Centre in Accra aims to create a cultural hub for academics, the diaspora and the local community. Balancing preservation and new construction, the revitalised campus will feature a museum, restored home, mausoleum, amphitheatre and green public spaces, emphasising sustainability and historical integrity.

Located in Johannesburg, the Thabo Mbeki Presidential Library will be a centre for learning, research and cultural exchange focused on the African perspective. It will feature a museum, research centre, auditorium, women’s empowerment centre, reading room and archive, seeking to help preserve and distribute African history and knowledge.

The MOWAA Institute, located in the Benin City Cultural District, will offer state-of-the-art facilities for conservation, study, and exhibition of historic artworks. This sustainable, single-storey building will feature locally sourced materials, secure storage for artifacts, laboratories, a visitor centre and an amphitheatre, supporting ongoing archaeological research and community engagement.