Office-to-residential conversions may become increasingly popular, so what does it cost to turn a commercial space into a home? Ben de Waal and Chris Amesbury of Davis Langdon, an Aecom company, look at the conditions needed for success and the key financial considerations

01 / INTRODUCTION

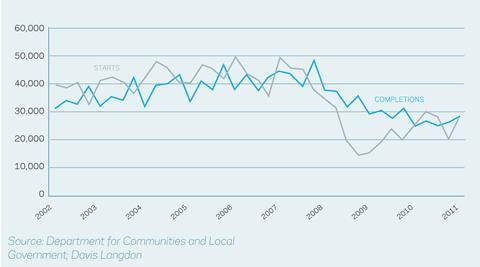

The need for new homes is not in dispute. Housing output has declined to less than 50% of 1980 levels and is at its lowest in England since 1923. In 2010, the private sector increased the number of completions but these were still two-thirds of the number it was building in the mid-2000s.

According to the Institute for Public Policy Research, there is a projected housing shortage in the UK of 750,000 units by 2025. Lending to first-time buyers continues to fall, with lending down 17% on the same period last year. And according to research carried out by the Smith Institute, home ownership is likely to fall by 2 million in the next 10 years, with the private rental sector set to grow to about 25% of the market.

Supply of land for housing remains constrained due to the lack of land and buildings fit for development and conversion, while the planning system remains burdensome, expensive and uncertain. In fact, 40% of local authorities are unable to identify a satisfactory supply of land for new homes and many of these authorities are in areas of highest demand.

The position is clear. A more diverse housing supply is needed to accommodate different tenures, with the greatest need reserved for affordable housing and the predicted growth in the intermediate rental sector.

Local plans need to identify the land and buildings allocated for housing, and ensure that the necessary public services are in place. In addition, buildings need to be flexible and adaptable to accommodate changes in the way people live and use them.

02 / THE CASE FOR OFFICE CONVERSIONS

Historically, only 2-3% of new dwellings built each year have been on land previously used as offices. But with office vacancy rates now in excess of 10% in most regions outside London, the potential for conversions should not be ignored. The government has put forward proposals to allow, as permitted development, the conversion of office space to residential. By doing so, this will bring underused and vacant properties back into economic use, providing an estimated 7,000 new dwellings a year.

The idea of converting buildings to homes is not a new one. The idea gained favour in the mid-1990s as a result of the massive oversupply of office space built in the late 1980s, coinciding with an increase in residential values and a growing appetite for urban living. Conversions became viable and developers simply responded to market demand.

The viability of office conversions needs to be seen in the context of the relative performance of the residential and office markets in the area concerned, as well as the cost of the conversion itself. There are many supply and demand factors that contribute to this. These include demographic and labour market changes; consumer appetite for urban living; exchange rates and their influence on overseas demand; provision of local services, schools and transport links; planning constraints; and mortgage and development finance liquidity.

One of the most significant factors influencing the market today is the amount of surplus local authority office space coming on to the market with negligible economic value for its current use. Authorities will naturally be cautious about releasing too much commercial space for conversion, with the risk of either compromising the area’s attractiveness as a business destination or inadvertently forcing commercial rents to rise through undersupply. However, they will equally want to guard against long-term disuse and the degenerative effect it can have on an area. This should therefore ensure that conversion is considered as a real alternative in the development of their local plans.

Given the overall sustainability agenda, there is certainly strong logic to living closer to our places of work and reusing buildings that would otherwise be redundant. However, whether the permitted development proposals will have the desired impact remains to be seen. Any conversions requiring changes to

the external facade or external works will still need planning permission and a number of questions remain unanswered, such as the process for determining affordable housing quotas and other planning gain measures to deal with transport and parking implications, and how to address the noise implications created

by use changes. The expectation is perhaps that the market will drive these issues to a sensible outcome.

While many conversions will be carried out for sale, there is an increasing interest in residential investments, with rents up by an average 4.2% since July last year in England and Wales and by 7.1% in London, as measured by LSL Property Services buy-to-let index. The private rental market is still dominated by the largely unregulated buy-to-rent market but there is growing interest from pension funds attracted to returns that match their annuity profile and from registered providers and local authorities seeking investment in mixed-tenure developments. Office conversions can provide a route for these types of investments, especially in areas of low office values or in areas where there is a strong rental market.

03 / FISCAL POLICY

Despite the public spending cuts, the government remains committed to reversing the downward trend in housing delivery and has taken some clear steps to encourage growth.

It continues to provide grant support with the injection of £4.3bn of funds into the affordable rent sector, aimed at providing 170,000 homes by April 2015. In addition, the implementation of the New Homes Bonus, an incentive paid to local authorities equal to the council tax levied on each new home for a period of six years, is expected to inject a further £1bn over the next four years.

Further measures are also being provided through the likes of the FirstBuy scheme, which provides access to funding for first-time buyers and will help more than 10,000 first-time buyers in England over the next two years. The government has made £250m available over this period for this programme.

Conversion projects often give rise to opportunities to save money through tax relief, either directly or indirectly. The VAT rules associated with residential property are complex, although, where a commercial building is converted to residential, the works are subject to a reduced rate of 5%. If the property is listed, then approved alterations carried out in compliance with the listed building consent may be zero-rated.

In any event, professional fees (unless novated to the building contractor), carpets, certain furniture and kitchen appliances are always standard-rated. Once complete the first sale or lease over 21 years is zero-rated; however a shorter lease will be exempt for VAT purposes meaning that any input tax incurred will not be recoverable.

Land remediation relief also provides an opportunity for companies to get tax relief on remediation costs, including the removal of asbestos in existing buildings. Its life is potentially limited, with proposals for its abolition in April 2012 part of an ongoing consultation into tax simplification measures. However, while the relief remains, there is an opportunity to generate a cash benefit that can be as high as 39% of the cost of remediation.

Also, while capital allowances are not available on chattels and fixtures installed within the actual dwelling units, there is an opportunity to claim plant and machinery allowances in common parts, such as lifts, centralised heating systems and incidental building works and this may well, for example, influence the decision regarding whether to go for a centralised or at-source heating solution.

Where renewable energy technologies are utilised, feed-in-tariffs and the renewable heat incentive provide cash payments for up to 25 years for eligible installations.

Some of these installations also qualify for 100% tax relief through the Enhanced Capital Allowances programme, although this accelerated benefit is currently under consultation with HM Revenue & Customs. Further information can be found at www.bankingtaxfinance.com, once it becomes available.

04 / PUBLIC SECTOR PARTICIPATION

With the greatest need for new housing being in the social housing and intermediate housing sectors, the latter being those people who are not in receipt of social benefits but cannot afford to buy, local authorities and registered providers are both likely to have a significant influence on the market going forward.

On 1 April 2012, the government is set to abolish the Housing Revenue Account Subsidy System and introduce self-financing for council housing. The reforms are expected to pass control of more than £300bn of rental income to local authorities over the next 30 years, which could free up more than £50bn for new housing and improvements to the existing stock. Local authorities also have control of their surplus office space and may well be prepared to trade land value for more social housing provision, removing a land cost from the development appraisal that would bring benefits through cash flow and savings on construction finance.

Despite the removal of social housing grants, there is still government support for registered providers through the affordable rent grants. Registered providers will, nonetheless, need to explore new ways to develop without a grant. Some will turn to the bond markets for funding, with Places for People recently raising £175m in the social housing sector’s first unsecured issue on the UK bond market.

Sale of stock will seem attractive in the short term but is ultimately not sustainable and it is questionable whether the sales expertise and brand exists to adopt a housebuilder-type model. There is, however, a growing appetite for institutional-type lease arrangements involving registered providers as the tenant in mixed-tenure investment properties. The registered providers’ covenant strength remains strong and therefore more attractive to investors who are unwilling to take the risk on void levels and running costs.

05 / KEY COST DRIVERS

When considering the key cost drivers for a refurbishment scheme, it is worth considering the advantages when compared with a new-build alternative. First, and most importantly, the time savings generated from not having to go through planning and from having a reduced construction programme can have a significant impact.

It is anticipated that a 1% shift in floor space from office to residential would lead to savings of about £100m in today’s money from planning savings alone. This not only increases the attractiveness of conversions when considering existing under-utilised space, but it also means that returns can be made over a shorter period of time, enabling greater churn of available cash flow.

The key cost drivers for a refurbishment or conversion scheme are likely to centre on the ability to use the existing structure and foundations and elements of the existing facade.

If the structure is not particularly suitable for residential use, the cost and time implications of significantly altering an existing building may eliminate any perceived economic advantage over a new-build alternative.

When considering the approach to replacing or refurbishing the facades on the building, the adopted solution will need to achieve not only the requirements of the ��ɫ����TV Regulations in terms of thermal performance (Part L), but also the objectives of the facade in relation to the design intent and target market. For example, if the building is targeting the prime market, the facade is likely to require wholesale replacement adopting high-quality materials and may be delivered through a bespoke curtain walling system. In comparison, a refurbishment scheme delivering affordable housing may incorporate a simpler repair and refurbishment of the facade.

Establishing the ability of the existing structure and facade to accommodate the potential alterations will enable key decisions to be made with a level of confidence and can minimise premiums for risk. Similarly, the selection of a “total envelope” contractor may provide a single point of responsibility for the design, procurement, production and installation of the facade, reducing the inherent risk.

Other key cost drivers worth considering are the services installations and the level of quality required from the finishes. In a conversion from office to residential space, it is likely that the central plant requirements will be reduced. This can provide opportunities to reconfigure space at ground floor/basement levels that can be used for other purposes, such as parking or residents’ facilities. The location of chillers within high-quality buildings requires careful planning and consideration, as the penthouse levels offer the maximum value opportunities and locating plant at these levels should be avoided where possible. The planning of service cores also needs consideration to allow lettable floor space to be maximised while also allowing flexibility in the floorplate layouts on each floor.

One of the emerging cost drivers for residential projects is the requirement to achieve ever more stringent energy performance and sustainability levels. The communities department has recently released an updated cost review document outlining the anticipated cost of building to the Code for Sustainable Homes for different project types. With the government’s target of achieving zero-carbon across all new- build housing types by 2016, it is important to factor in the likely sustainability targets within any planned scheme. The summary of likely costs contained within the review, which was released in August 2011 and included costs prepared by Davis Langdon, shows that the cost uplifts for achieving code levels 4, 5 and 6 are approximately 10%, 30%, and 50% higher than costs for schemes measured against a Part L 2006 baseline.

For refurbishment or conversion schemes, the rules on sustainability are different, in that the performance of the building is measured against the old EcoHomes targets rather than the Code for Sustainable Homes. This can result in significant cost differences when comparing options for either a new-build or conversion residential scheme.

Taking into account the various key cost drivers, it can be seen that opportunities exist to realise cost savings through the refurbishment of buildings, but these need to be measured against any potential implications on value. In high-quality residential schemes with new high-quality facades and fairly extensive remodelling of structure, the savings are likely to be limited to a maximum of 10% of the overall costs. This compares with affordable schemes, where the structural and facade elements are likely to form a major part of overall costs, meaning potential savings could be far greater and could reach up to 20% or 30%.

06 / FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE DESIGN

One of the key factors influencing the design of a refurbishment scheme will be whether opportunities exist to realise the ultimate value of the asset. Understanding whether the existing structure can accommodate a vertical or horizontal extension will significantly influence the ultimate design solution, as will establishing the extent to which the existing structural core can be readily manipulated to provide an efficient residential floorplate.

Many existing office buildings will be able to accommodate these types of alterations without major impact on the existing substructure and frame, and can have a significant impact on the viability equation. A simple two-storey extension

to an existing building could readily add 10-20% to the potential value of the scheme, particularly when higher values likely to be achieved at the top of the building are taken into account, while an extension to an existing floorplate could add significantly more.

An early appreciation of the specific requirements of the target market will also allow the overall design to be progressed with the ultimate purchaser/user in mind. As purchasers become more demanding in their requirements, any refurbishment project needs to be able to compete head-to-head with the attributes of a new-build scheme, otherwise the ultimate value of the development could be compromised. Schemes in key locations, which can accommodate well-designed space with high-quality external and internal finishes and can provide complementary ancillary uses, will be attractive not only to the requirements of funders, but also to investors.

Incorporating suitable ancillary space at the lower levels of the building may also create additional revenue, either through the creation of independent rental space or by increasing the ultimate value and desirability of the residential element. Those uses that enhance the value of the latter while providing additional value are likely to provide the best returns, such as good-quality food retail and parking located in prime central London markets.

Finally, the need to accommodate affordable housing or a more significant commercial element will bring a number of design considerations into play, such as the separation of ground-floor entrances, plant and servicing strategies, facade treatments, and core arrangements. The efficiency of the building is likely to fall quite significantly and costs are likely to be higher for each component than in a single-use building.

07 / THE COST MODEL

The cost model shown on the next page considers the potential costs for converting an existing office building into a residential building that provides a good-quality level of accommodation. The existing building is arranged over 15 floors, with a single level of basement, and a gross internal area of 17,600m2.

The existing building is concrete framed with a central core, and the proposed scheme includes alterations to the core to ensure the residential sales areas are maximised.

It includes the replacement of the existing facade with a new facade and has a solid-to-glazed ratio of components that are necessary to achieve the thermal performance demanded by Part L of the ��ɫ����TV Regulations.

The accommodation itself is completed to a level that includes fully-fitted kitchens and bathrooms, with wardrobes to each of the bedrooms. Floor finishes are provided throughout. Heating is provided through an underfloor heating system, which is fed from the centrally located boiler system. Comfort cooling is not provided and the model includes the cost to replace the existing central plant.

Costs given are Q3 2011, based on an outer-London location and assume a lump-sum, single-stage design-and-build contract. Main contractor preliminaries and contingencies are included, but demolitions and site preparation, external works and services, professional fees and VAT have been excluded.

08 / CONCLUSION

Where costs do not prohibit development, the conversion of office and other B class commercial space does genuinely provide an opportunity to make inroads into the significant undersupply of homes. While there will be a need to ensure an area’s commercial offer is not overly compromised, the option of conversion is likely to be increasingly considered as a realistic option for any vacant office space that comes onto the market. This is not meant to imply wholesale conversion in all locations, rather another alternative in an increasingly flexible attitude to the way we use our built assets.

09 / LOCATION FACTORS

Location factors vary over time depending on regional market conditions. The cost of a building

is affected by many localised variables to produce a unique cost, including market factors such as demand and supply of labour and materials, workload, taxation and grants.

The physical characteristics of a particular site, its size, accessibility and topography are also contributing factors.

While all these factors are particular to a time and place, certain areas of the country tend to have different price levels than others. The location factors given in the table on the right are an attempt to identify some of these general differences.

Downloads

Cost model residential

PDF, Size 0 kb

No comments yet