With a rapidy ageing population demanding high standards of both housing and care, while also imposing a rising cost on public finances, could ÔÇťextra careÔÇŁ housing be part of the solution?

01 / Introduction

The UK has an ageing population. The Office for National Statistics forecasts that the number of people over the age of 60 will increase by 7 million over the next 25 years.

Unprecedented financial pressures affect the provision of housing for older people through reductions in public funding. These include withdrawal of support for housing private finance initiatives, cuts to local authority grants, the impact of welfare reforms and the attempts to integrate adult social care and the NHS while the latter is being restructured.

The challenge of housing an ageing population is thus an ever-increasing problem.

Everyone involved needs to identify solutions that will meet the housing expectations of an increasingly ageing population whose members are also more demanding than ever in the type of accommodation they consider acceptable - old-style sheltered housing is no longer sufficient.

It is therefore vital that local authorities, registered providers, developers and the health and social care sectors develop partnerships and work together to find solutions.

Government policy

In its 2011 paper Laying the Foundations: a housing strategy for England, the government committed itself to ensuring that housing and planning policies reflect the wide range of circumstances and lifestyles of older people, who already occupy nearly a third of all homes, and that they can make an informed choice about their housing and care.

Nearly two-thirds (60%) of the projected increase in the number of households from 2008-2033 will be headed by someone of 65 years of age or over.

Laying the Foundations also set out policy on how to plan for homes and communities that enable older people to be economically active, involved with families, friends and community and able to choose where and how they live.

This not only makes financial sense, but also seeks to foster a more inclusive society as provision of good housing for older people could enable them to live healthy, independent lives and so reduce pressure on working families in caring for older relatives.

Good housing can also reduce costs to the NHS and social care by preventing medical conditions that may arise if people live in lower standard accommodation.

Many older people choose to move home to remain independent, to release equity and to access appropriate support and care, and this can sometimes have the additional benefit of freeing up scarce local family housing.

Laying the Foundations stated the government is working with planners and developers to facilitate industry-led guidance to enable the local strategic planning and delivery of a wider range of innovative, high-quality housing for older people based on robust data and needs analysis, including demographic projections and profiling.

Planning policy encourages local authorities to provide for a wide range of housing types across all tenures, including accessible and adaptable general-needs retirement housing, and specialised housing options including sheltered and extra care housing for older people.

02 / What is extra care?

David Hughes, senior partner of architect Pozzoni and a specialist Extra Care designer, points out other titles are sometimes used including ÔÇťassisted livingÔÇŁ, ÔÇťhousing with careÔÇŁ and ÔÇťvery sheltered housingÔÇŁ.

He says: ÔÇťWhatever their precise name, essentially, extra care units are self-contained homes with design and support features to enable self-care and independent living. The principle is to allow people to maintain an independent lifestyle but they may need some extra care to do that.

ÔÇťThe key factor that differentiates extra care from sheltered housing or retirement housing is the 24-hour presence of care staff on site. Care is not brought in on a visiting basis.

ÔÇťExtra care developments are often accessed from a communal corridor in a single building but there are many developments of conventional bungalows and houses.

ÔÇťAll these developments will have shared communal facilities, some of which can be quite extensive.

ÔÇťExtra care schemes aim to create a ÔÇśhome for lifeÔÇÖ where care is brought to the resident as needed. Residents should not have to move if their care needs change, because the building design and construction is flexible and adaptable to accommodate an individualÔÇÖs changing needs.

ÔÇťExtra care is mostly for older people, but not exclusively. There are developments for people with learning or physical disabilities, which have adopted the same principles.ÔÇŁ

03 / Design issues in extra care

Older people can be sensitive to their surroundings and the design of the built environment can have an impact on their welfare.

Good design should create an environment that enables people to have independence, choice, maintain their lifestyle and have contact with the wider community.

Extra care developments should be a ÔÇťhome for lifeÔÇŁ for residents, which as far as possible enables them to compensate for impairments that may include reduced mobility, vision and hearing and cognitive loss (including dementia).

Older people can also be more sensitive to changes in temperature so careful consideration of the environmental design is important.

Extra care should create an environment that is domestic and homely, one of which residents can be proud and that enhances their quality of life.

Its design should facilitate the efficient delivery of care and support for the residents and enable the staff to manage both the building and care delivery.

It should also create opportunities for residents to have privacy, comfort, support and companionship, both in their own private spaces and as part of a vibrant community.

This means that the design should balance commercial issues of construction and operating costs with the space and configurations needed to accommodate residentsÔÇÖ lifestyles.

There also needs to be a mix of tenure options and the flexibility to change according to care needs and market conditions.

In some cases, extra care housing will additionally function as a community hub and resource base, and this should be allowed for without compromising the privacy and security of residents.

Key design factors

The Housing our Ageing Population: Panel for Innovation (HAPPI) report was published in 2009 following in-depth research of housing for older people across Europe, and was followed by the HAPPI2 report in 2012. It made 10 recommendations for the design of housing for older people:

- Generous space standards and flexibility

- Maximise daylight, particularly into circulation spaces, for example, with single bank corridors

- Natural light and ventilation with balconies and patios for private external space

- Ensure adaptability and ÔÇścare readinessÔÇÖ so that assistive technology can be easily installed as and when required

- Make a positive use of circulation space to create opportunities for social interaction and natural surveillance

- Communal facilities should also be able to serve as a community hub if required

- The public realm should enhance the natural environment

- Homes should be energy efficient but avoid overheating

- Adequate storage, both for household storage plus mobility aids and bicycles

- Create shared external surfaces such as ÔÇśhome zonesÔÇÖ.

While few would disagree with these principles, there has been some criticism that there was little apparent consideration of cost or potential site constraints, though HAPPI2 discussed reducing the footprint for communal areas and a greater use of technology among other refinements.

04 / Trends in the development of extra care housing

Community hubs

Extra care schemes are increasingly becoming community hubs. This is where they become a base for home care, health, social care and other services provided for the wider local community, not just those services delivered to residents.

When the communal facilities in extra care schemes are accessible to the public, such as a caf├ę, hair salon, or well-being suite, for example, this brings life and activity into the scheme and residents can still be part, actively or passively, of their wider neighbourhood. Many extra care schemes now use or rent out their multi-purpose room as a village hall.

Joint commissioning: health & social care

Extra care housing is being recognised as an essential component of joint commissioning by health and social care services. It has an increasingly common role for intermediate care and rehabilitation helping to overcome bed-blocking of hospital beds by allowing patients to move to an extra care facility when they would otherwise be unable to leave hospital since their own home might no longer suit their care needs.

Components in larger care schemes

Several developments now have an extra care building within a larger campus that can include a care home for people with high-dependency needs and retirement dwellings for people who are more independent.

Densities and regeneration

With land and construction costs increasing there is pressure for higher density developments that cater for a wide range of needs.

Extra care schemes may also be used for regeneration as they can sometimes be used to meet the ÔÇťaffordable housingÔÇŁ element in Section 106 agreements, with the additional advantage that those moving into them may release family-sized houses onto the market.

05 / Factors in extra care

The necessity of good partnerships at both a strategic and service commissioning level is vital, as good commissioning cannot be done without these. Such partnerships should include the private sector as well as social providers.

Funding the investment to achieve strategic priorities requires commissioners from health, housing, care and support working together. There are also regional changes affecting funding for housing and planning that must be understood.

It is vital to have intelligence about local markets and demand - to understand local supply and ensure that service commissioning for extra care takes account of what can be used and re-used or re-modelled.

The philosophy of independent living and re-enablement requires different staff skills and ways of working for care providers and has implications for their workforce planning.

The Housing Learning and Improvement Network provides a wealth of resource material, references and case studies for extra care housing.

06 / Considerations when converting sheltered housing to extra care

Many registered providers have outdated sheltered housing and are considering converting these properties to extra care. In principle, this should be a sensible approach. However, practicalities often prevent successful conversions.

Typically, sheltered housing flats are undersized, sometimes only bedsits. Their corridors may be narrow, creating problems for wheelchair users, flat layouts often provide poor mobility access, requiring internal re-planning, and lifts may be undersized for wheelchair or bed / stretcher use.

Additionally, value added tax is payable on conversions, which, when taken with other costs, may make a new-build a more attractive option as the tax does not apply there.

David Hughes, of Pozzoni, recalls a project at Pickmere Court, Crewe, where Wulvern Housing redeveloped a sheltered block as part of a larger extra care development.

He says: ÔÇťThe existing flats were small, with poor circulation. These were improved by widening their entrance halls, refitting kitchens and installing level access showers and by adding a bay extension to living / dining rooms.

ÔÇťEven so, the resulting flats are best suited to single residents. The existing corridors are narrow, and have been enhanced by forming a recessed ÔÇśfront porchÔÇÖ at flat entrances.

ÔÇťAn extra floor was added over the flat-roofed building, providing additional, larger apartments and visually tying the converted block into the contemporary later phases.

ÔÇťThe communal facilities were added in a separate, linked single storey block, which serves the whole scheme and the wider community.ÔÇŁ

07 / Financial challenges for extra care

Extra care faces a variety of financial issues, which have proved especially difficult in the recent economic climate. Capital finance is hard to secure, and lenders may stipulate onerous borrowing criteria. While there has been government funding via the Homes and Community Agency (HCA), this is available for registered providers only and demand exceeds the money available.

A stagnant housing market has meant that older people who wish to move may find it difficult or impossible to sell their home to finance move into an extra care scheme, although the recent upturn in the housing market should see this challenge lessen.

Since extra care schemes have larger space standards and communal facilities not found in conventional apartment developments, this extra cost is reflected in their prices or rents, meaning that intending occupants have to be able to raise a larger sum than they would were they to move elsewhere.

Optimum sizes

While there are many small-scale developments across the UK, these pressures indicate that an extra care development requires a minimum of 40 units to be economically viable.

At the other end of the scale there are several very large extra care villages, each of several hundred units, achieving an economy of scale but with careful design and management required to ensure community links are maintained so as to avoid the inadvertent creation of a retirement ghetto.

There are also issues arising from pressure on land, land costs and maximising density to achieve an economy of scale.

Welfare reforms such as changes to pensions, housing benefit, and the bedroom tax all also bring uncertainty, although their impact is more on younger people.

08 / Planning and policy challenges for extra care

Drawing on his experience of negotiating planning permission for extra care developments, David Hughes notes: ÔÇťIn planning use class terms, extra care housing is neither C2 (residential institutional) nor C3 (dwelling houses) but is sui-generis (without classification).

ÔÇťDifferent planning authorities have different interpretations of this, so there is inconsistency across the country as to what constitutes extra care, and planning conditions may be imposed to prevent a conventional block of flats being developed by just calling the proposed development ÔÇśextra careÔÇÖ.

ÔÇťSuch planning conditions can include a requirement for residents to receive a minimum number of care hours per week or that residents having a diagnosed medical condition. There have been calls for a new planning use class for extra care housing.ÔÇŁ

Dealing with dementia

David Hughes notes catering for residents who have dementia can affect a projectÔÇÖs design:

ÔÇťAlong with the ageing population, there are an increasing number of people being diagnosed with dementia. Dementia can affect people in different ways and good design can compensate for its impairments.

ÔÇťAnecdotal evidence shows that while extra care housing is suitable for people with relatively low or mild levels of dementia, it is not suitable for people with its more severe forms, who inevitably have to move on to a specialist high-dependency care environment, which contradicts the principle of a ÔÇśhome for life.ÔÇÖ

ÔÇťProviding a dementia care facility on site can, to a degree, resolve this, as an individual is still in the same place and with the same housing provider, hence the rise of ÔÇścontinuing care communitiesÔÇÖ.

ÔÇťThe Housing and Dementia Research Consortium has been set up by several of the larger housing providers to initiate in-depth research into how extra care can be suitable for people with dementia.ÔÇŁ

Community balance

There are also points to note concerning the balance of extra care communities.

He says: ÔÇťIn recent years, many local authorities have viewed extra care as a less expensive option to care homes, and have closed these and decanted residents into extra care. Often this creates an inappropriate community in the extra care scheme, with an over-provision within the apartments and challenges in maintaining adequate care and supervision.

ÔÇťSuccessful extra care schemes should maintain a balanced community with differing levels of need, where true independent living is promoted.ÔÇŁ

09 / Conclusion

The key challenge for all concerned with extra care housing is to create attractive, affordable homes so that people can make the positive choice to move to specialised housing, not being admitted at a point of crisis.

Design is only part of the jigsaw; the people and community are equally important.

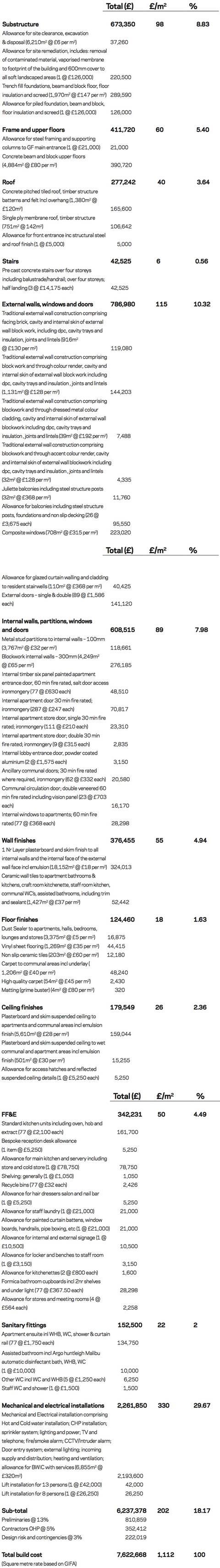

10 / Cost model excluding site works

The cost model is for a three-storey, traditional construction, extra care facility in the north of England. Costs exclude site works for the development which comprises 77 one and two bedroom apartments covering a gross internal area (GIA) of 6,855m2.

Paul Donlan: Director at Aecom, head of affordable housing Europe. With thanks to David Hughes, senior partner of Pozzoni for his contribution.

No comments yet