The Stirling has sometimes been used by the judges to indulge in virtue signalling, but this year it simply recognises brilliant architecture, writes Ben Flatman

The Stirling shortlist is often baffling, with great buildings regularly left out, and some not especially good ones sneaking in. This year was no different, with several decent but essentially rather ordinary projects in the running.

And not all the buildings in the winners’ club have stood the test of time. In 2000, Caruso St John’s New Art Gallery in Walsall lost out to Alsop & Störmer’s Peckham Library. The gallery stands out as one of the best public buildings of the early 21st century, whereas the library now looks like the forlorn relic of a bygone era, when architecture was all about crazy shapes, and wonky piloti were all the rage.

There has also often been an annoying tendency to use the prize as a form of political messaging, responding to a perceived societal crisis in education or housing, rather than as a recognition for great architecture. But this year’s victor has cut through the handwringing and the need to virtue signal. Finally, it feels like excellence in design is the winner.

This was Níall McLaughlin Architects’ (NMLA) fourth Stirling prize nomination, and it was beginning to look slightly ridiculous that the practice had not yet won. Each of the practice’s previous shortlisted projects would have been worthy of the top prize.

They included a conference centre for Worcester College, Oxford, social housing in Whitechapel and a chapel outside Oxford, but each year NMLA was pipped to the post.

>> Also read:

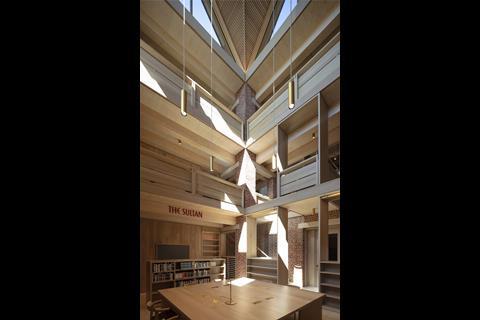

Not this time. It is a credit to this year’s judges therefore that they looked beyond the cost-of-living crisis and wider economic turmoil to choose a building (pictured, above) that could easily have been dismissed as too elitest or too posh. Instead, they selected the New Library because ultimately it concentrates on what defines good architecture – a thoughtful response to context, skilful manipulation of proportions, light and space, and exquisite use of materials and detailing.

It is also notable that this is the first time that a building for an Oxbridge college has won the Stirling. For years the institutions of Oxford and Cambridge have been commissioning some of the best UK architecture, and yet, perhaps because of perceived elitism, they have rarely been acknowledged as the enlightened patrons that they are. Arguably NMLA’s win therefore also represents an overdue recognition of what Oxbridge has done for British architecture.

My first encounter with McLaughlin himself was at university, when he was presenting one of his early projects to a room full of students at the Bartlett. It was, for want of a better word, very “Bartletty”. It was eye-catching but felt ephemeral and slightly lightweight. His practice’s output today seems a world away from that early work.

There is a strong Louis Kahn influence in this building, as there was with NMLA’s 2011 student accommodation for Sommerville College. It is as if, over time, McLaughlin has reconnected with his own educational roots at University College, Dublin, which is associated with so many towering talents in contemporary architecture.

It is not a perfect building. I found the way in which the long gallery leads to nowhere an unsatisfactory resolution of the ground-floor circulation. And the fact the massive double oak electric entrance doors need to be opened every time someone enters or leaves is surely both energy inefficient and somehow overwrought.

It is a library that students will be drawn to, comforted by and remember fondly for the rest of their lives

Most of the people coming in and out of the building will be students darting between lunch and tutorials. The doors don’t seem appropriate to the task they have been assigned.

But overall, this is sublime architecture. The budget and cost per square metre is not given. Perhaps it is an expensive building by everyday standards, but I am sure that plenty of architects would have taken equally generous budgets and produced mediocrity.

The New Library at Magdalene represents a type of architecture that we have often shied away from in the UK in recent decades. It is not modular, or extensively prefabricated. It is traditionally built, using handmade bricks and a lot of timber.

We talk a lot about sustainability in architecture, and for very good reason. But far too little attention is paid to the longevity of buildings. Thankfully we are becoming increasingly aware that 30 and 40 year lifecycles are no longer acceptable.

The mindset that saw architecture as a disposable commodity led to an attitude that ignored the way in which buildings age, and the value that old buildings deliver in terms of social and mental well-being.

This is a building that has been designed to last 400 years, and the architects have responded with something that you can tell has already established itself in the subconscious of college life. It is a library that students will be drawn to, comforted by and remember fondly for the rest of their lives. It’s the sort of architecture that people love to inhabit, and that they will continue to love to inhabit for centuries to come.

Postscript

The jury for the 2022 RIBA Stirling Prize was: Simon Allford (RIBA president and chair), architects Glenn Howells (founder of Glenn Howells Architects) and Kirsten Lees (managing partner at Grimshaw), and artist Chris Ofili. The jury was advised by sustainability expert Smith Mordak (director of sustainability & physics at Buro Happold).

No comments yet