Stanton WilliamsÔÇÖ revamp of the Royal Opera House works as an evolution of Dixon JonesÔÇÖ earlier scheme, further opening up the building to make it more accessible as a public space, including improving its access from Covent Garden Piazza.

One of LondonÔÇÖs many oddities is that for hundreds of years the neighbouring landmarks of the capitalÔÇÖs most prestigious performance venue and its showcase public square effectively turned their backs on each other. In most continental cities the Royal Opera House would probably have a grand entrance facing on to Inigo JonesÔÇÖ seminal Covent Garden Piazza.

But when the first iteration of the present opera house opened in 1732, LondonÔÇÖs voracious private property market all but demanded that the established residential structure (and commercial revenue) of the piazza be preserved, thereby roundly trumping public entertainment. Consequently, like the British Museum and the original environs of Westminster Cathedral, in the Royal Opera House we see the main entrance to yet another major London public building relegated to a side street.

It is this social and historic anomaly that the Royal Opera HouseÔÇÖs latest revamp seeks to address. The institutionÔÇÖs ┬ú37m Open Up expansion and refurbishment programme was completed earlier this month.

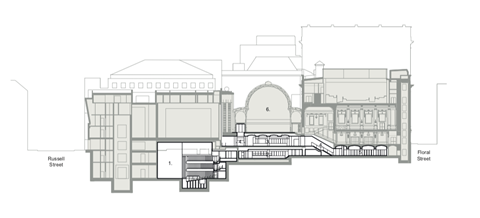

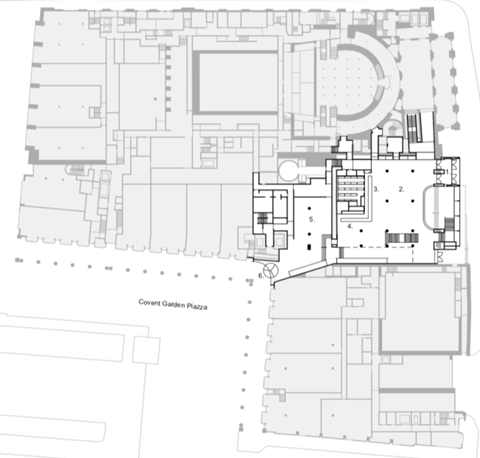

While Edward BarryÔÇÖs original historic facade, foyer and 2,200-capacity auditorium of 1858 have been left virtually untouched, architect Stanton Williams has provided new entrances and new foyer spaces and radically reworked attendant restaurant and recital spaces. Additionally, circulation space has been extensively reorganised, and the number of toilets doubled. Crucially, the revamp also seeks to improve the opera houseÔÇÖs rear entrance onto the piazza.

Of course in the current buildingÔÇÖs long history there has been one other major reworking, Dixon JonesÔÇÖ heroic ┬ú200m overhaul of 1983-99. As might be expected, the enduring presence of this scheme looms large over the current works. As well as major reconstruction and expansion of key parts of the building, including the magnificent glass Paul Hamlyn Hall, for the first time the Dixon Jones scheme created a new rear entrance directly on to the piazza, and enhancing this was a key part of Stanton WilliamsÔÇÖ brief.

Opening up

Royal Opera House project manager Sarah Younger explained the latest projectÔÇÖs ambitions: ÔÇťWe want to open up the building so that it becomes more than just a ticketed theatre. WeÔÇÖve learned from the success of projects like the Tate Modern and we want to provide a very public offer that provides the kind of full-day cafe, shop and leisure experience you now find in art galleries and museums while differentiating between opera-goers and other visitors in a careful and discreet way.ÔÇŁ

For all their gilded grandeur, opera houses are not normally considered particularly public or socially accessible buildings, particularly during the day. So the project seeks a major shift in the way that an opera house as a building type is both used and perceived. This is a task made all the more challenging by the fact that, along with La Scala in Milan, the Bolshoi in Moscow, Teatro di San Carlo in Naples and Teatro Col├│n in Buenos Aires, Covent Garden is considered one of the worldÔÇÖs five great opera houses.

Equally, achieving the invasive level of physical alteration in a revered and historic building presents obvious challenges. Particularly when the opera house stayed open throughout the three-year project and continued its impressive programme of hosting almost 1,000 performances a year and welcoming 40 million annual visitors from around the world.

Technical challenge

By far the most onerous technical challenge of the build involved creating a new Bow Street entrance beside BarryÔÇÖs principal facade and new double-height foyer. This also required significant basement excavations and, most ambitiously, the installation of two gigantic structural trusses to support a significant part of the 160-year-old grade I-listed building.

When Dixon Jones rebuilt BarryÔÇÖs original Paul Hamlyn Hall ÔÇô then called the Floral Hall ÔÇô in the 1990s, it created a new supporting concrete beam and new foyer space underneath it. Previously the area beneath the hall presented a blank frontage to Bow Street and incorporated fire exits arranged between structural columns that supported the hall above.

Forming a new entrance within this previously solid facade was a key ambition of the Open Up project. This has been achieved by the insertion of a continuous glass wall along Bow Street that allows direct views in and out of the expanded foyer, providing the openness and transparency that the project seeks at its core. This wall has been pushed forward of the Paul Hamlyn Hall facade above, cleverly allowing for the creation of a new roof terrace that leads out from the floor of the Paul Hamlyn Hall itself.

As well as the new entrance and glass wall below the Paul Hamlyn Hall, the foyer beyond it has been extended down into the basement along this new street frontage. This helps double the amount of foyer space throughout the building and also helps improve accessibility to the 400-seat basement Linbury Studio Theatre, another Dixon Jones addition that the current project extensively refurbishes.

So, essentially, the new project requires the Paul Hamlyn Hall to float above a double-height foyer framed on its principal frontage by a glass wall. The solution to the structural riddle inherent in this arrangement is a pair of enormous concealed steel trusses that span the full length of the glass wall and support the retained concrete beam that in turn supports the facade of the Paul Hamlyn Hall above it.

The truss dimensions are impressive. The trusses span a full 15.3m and have a width of 300mm. At their deepest point the height is a staggering 1.35m, the maximum structural zone allowable to maintain a clear head height for the Linbury Theatre foyer below. The weight of each truss itself is 15 tonnes, and they are capable of supporting a total glazed facade weight of 40 tonnes.

The installation sequence required a controlled transfer of loads, initially from the existing structure to the temporary works and then from the temporary works to the permanent transfer trusses spanning the original historic structure. This process was aided by a complex system of real-time movement monitoring, load cells and jacking assemblies. In recognition of the sensitivity of the historic fabric, the trusses have been installed within an overall movement envelope of just 2mm.

Visual impact

While this new foyer and its attendant trusses formed the bulk of the projectÔÇÖs structural intervention, changes to the smaller rear entrance onto Covent Garden Piazza were also important. Previously, the entrance was a single large revolving door leading into the piazza colonnade. The concealed cores and structural walls on either side form a significant physical constraint that prevented this entrance from being enlarged.

However, the revolving door is now placed within a new curving glass wall structure prominently placed into the corner of the colonnade. A large LED screen has been incorporated into the glass wall, skilfully enabling the entrance to have a bigger visual impact, despite the fact it was unable to increase significantly inside.

Once inside the building, there is also now a clear visual link between the piazza and Bow Street entrances. One of the reasons why the Dixon Jones Bow Street frontage was blank was because of the stairway that ran behind it leading up to the Paul Hamlyn Hall. This has now been replaced by a new glass stairway that, unlike its predecessor, leads to the atrium serving the Paul Hamlyn Hall rather than to the hall itself. The result is that, for the first time, the Paul Hamlyn Hall can essentially be cordoned off independently rather than serving as a glorified circulation space for the venue.

The majestic Dixon Jones escalator that serves the restaurant on the top floor has been kept in place, and the restaurant itself has had glazing inserted to a selection of its loggia openings to form a winter garden. Now, as before, it offers spectacular views into the Paul Hamlyn Hall and out over the piazza below.

Stanton Williams co-founder Alan Stanton is keen to stress that his project is in no way a repudiation of Dixon Jones original work, but is more an ÔÇťevolutionÔÇŁ. He points out that Jeremy Dixon himself has shadowed the project informally and that many of the themes of openness and accessibility that the new scheme champions have their conceptual origins in the original Dixon Jones rework. The Royal Opera House project therefore represents a compelling case study in how sensitive structural ingenuity and spatial reorganisation can offer new interpretations of revered historic buildings.

Project Team

Architect: Stanton Williams

Client: Royal Opera House

Construction manager: Rise

Structural engineer: Robert Bird Group

M&E engineer: Arup

Cost consultant: Gardiner & Theobold

Project manager: Equals Consulting

No comments yet