After a tricky year for MMC, one start-up claims its asset-light business model will help it succeed where others have failed. As part of the ║├╔½Ž╚╔·TV the Future CommissionŌĆÖs focus on innovation in construction, we examine ModulousŌĆÖ TESSA software before its launch later this year

There has been no shortage of ink spilt or money spent on modern methods of construction since Mark FarmerŌĆÖs famous challenge to the industry in his 2016 report Modernise or Die. According to Make UK, a total of ┬Ż1bn of private finance has been invested in R&D and new modular factories since the reportŌĆÖs publication, bringing total UK capacity to 5,000 units per year in 2022; meanwhile Homes EnglandŌĆÖs affordable homes programme has introduced a requirement for developers signing strategic partnership deals to ensure 25% of homes are built using MMC.

With government and industry alike pinning their hopes on the technology, there is a growing sense that, if net zero targets are to be met and the mounting labour supply crisis is to be swerved, then modular building ŌĆō in one guise or another ŌĆō must be made to work. It was cause for concern then, that 2022 saw four modular businesses head down the ŌĆØdieŌĆØ route. Major financial trouble at Swan, Caledonian, House by Urban Splash and CountrysideŌĆÖs modular business have led some to question the sustainability of a market which requires high upfront investment in manufacturing facilities and research and development. Maintaining these facilities amid fluctuating demand for units has simply proven too much for some firms.

>> Find out more about the ║├╔½Ž╚╔·TV the Future Commission

But if expensive factories are the problem for MMC, what is the solution?

One modular start-up believes it has the answer: get rid of the factories. Set up in 2018, Modulous is an offsite housing firm with a difference. Unlike many others in the space, the company does not own any factories ŌĆō or indeed much in the way of physical assets at all.

Instead, it offers the use of its patented design and feasibility software, which creates customised development options based on ModulousŌĆÖ kit of parts solution. Once the developer has decided what it wants, the software automatically generates picking lists for all the components needed from the supply chain.

These components are manufactured as sub-assemblies at the national or regional level by supply chain partners ŌĆō including Knauf, CEMEX, Ideal Standard and Ibstock ŌĆō before being transported as flat packs to an assembly facility where they will come together as volumetric modular. After that, the completed units will be installed into the foundations, core and podium (they have yet to modularise these elements), built by a traditional construction partner. ŌĆ£A question we get asked is what category of MMC are we and the honest answer to that is we are sort of all of them,ŌĆØ says Chris Hartiss, design director at the firm.

The seven categories of MMC

MMC is an umbrella term that covers a spectrum of activity from category 1 under which whole 3D systems are manufactured offsite, to category 7 which is primarily traditional build with some use of technology to increase productivity.

Category 1 ŌĆō Pre-manufacturing ŌĆō 3D primary structural systems

Category 2 ŌĆō Pre-manufacturing ŌĆō 2D primary structural systems

Category 3 ŌĆō Pre-manufacturing ŌĆō Non-systemised structural components

Category 4 ŌĆō Pre-manufacturing ŌĆō Additive manufacturing

Category 5 ŌĆō Pre-manufacturing ŌĆō Non-structural assemblies and sub-assemblies

Category 6 ŌĆō Traditional building product led site labour reduction/productivity improvements

Category 7 ŌĆō Site process led labour reduction/productivity improvements

Source: Department for Levelling Up, Housing & Communities

This approach is all part of ModulousŌĆÖ philosophy of quiet revolution ŌĆō transforming the way houses are built but without biting off more than it can chew. ŌĆ£We feel that clients and contractors should be getting a pretty similar experience to what theyŌĆÖve always had,ŌĆØ says Hartiss. ŌĆ£We donŌĆÖt want to effect a revolution that starts right at the beginning, because thatŌĆÖs going to be too difficult to do, so this is based on a sort of design and build kind of model at the moment [ŌĆ”] A client will appoint a contractor in the usual way, the contractor will appoint design teams [and] subcontractors in the usual way and the supply chain sit behind them.ŌĆØ The client will also have an arrangement with Modulous, which will in some cases be in joint venture with the contractor.

This year could be pivotal for the firm, with its first units set to hit sites. By HartissŌĆÖ own admission, the companyŌĆÖs physical kit of parts solution, which it has been developing since 2019, is ŌĆ£not that far different from other[s]ŌĆØ on the market ŌĆō a hot-rolled steel floor casette with four columns into which Knauf-developed wall panels and pre-built wet walls and service zones will be installed and topped with ceiling panels.

But Modulous is a technology company as much as it is a construction firm ŌĆō its hiring decisions prove as much, with former Google, Microsoft and Netflix staff on the payroll ŌĆō and arguably it is its software which distinguishes it. ŌĆ£It became apparent that physical solutions and digital ones together, informing one another, were going to be the way forward,ŌĆØ says Hartiss.

ŌĆØWe get asked [ŌĆ”] what category of MMC are we and the honest answer to that is we are sort of all of themŌĆØ

Chris Hartiss, design director, Modulous

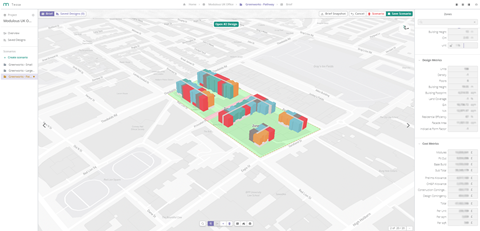

April will see the commercial launch of TESSA ŌĆō short for Tech Enabled Solutions for Sustainable Architecture ŌĆō a software platform that generates optimised schemes for ModulousŌĆÖ kit of parts on any given plot of land in the UK. It runs straight off a web browser, without the need for any special software or application and has been designed so that any property professional, whatever their level of qualification or technical sophistication, could use it.

A user can delineate a range of variables ŌĆō number of buildings per zone, number of floors, building height, unit type and mix ŌĆō and the software will spit out a variety of options for the site, comparing one against the other in terms of density, net-to-gross, residential efficiency and other factors. Further layers of information, such as topography and flood zones, can be applied and the firm plans to add more.

While ║├╔½Ž╚╔·TV was only shown the minimum marketable product, without the final user interface, it is fair to say this is not a design tool with a capital D. The selection of chunky, Lego-like massing pumped out by the software is only a starting point for developers and designer, promising to enable developers to reap all the theoretical benefits of modular development.

Users are given almost instantaneous ability to assess the viability of a range of different options for their project ŌĆō simplifying into minutes what would have taken weeks with a traditional approach.

In theory, this could also mean a simplified planning process and may even help foster a more collaborative relationship between developers and planner, with the former able to assess the feasibility of suggested amendments much more easily.

Hartiss, who worked for more than 17 years as an architect at Squire and Partners, envisions (perhaps optimistically) a future in which designers can sit down with local communities and planning officials to work out the boundaries of acceptability for each. It also provides early visibility of cost ŌĆō the benefit of a largely modular development being a high level of predictability ŌĆō feeding in a set of benchmark rates for the cost of work outside the kit of parts.

These, says Chris Spiceley, the firmŌĆÖs client accounts director, ŌĆ£would obviously need to be sense-checked by a QSŌĆØ, while metrics predicting the cost of ModulousŌĆÖ own kit of parts element will be updated to reflect what the firm is actually delivering in the market, meaning the toolŌĆÖs cost predictions should get more accurate over time.

Hartiss says that as the start-up has matured, its vision for TESSA has become more focused. ŌĆ£At the beginning, the software was going to be a big offering ŌĆō it was going to try and look at the whole process and try and digitise that,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£I think as weŌĆÖve matured, weŌĆÖve started to focus on parts of the process and really think about where added value isnŌĆÖt required now.ŌĆØ

Indeed, ModulousŌĆÖ whole business model seems to be centred on what is achievable, focusing its efforts on perfecting the modular technology for a particular building element (the basic living unit) in a targeted, specific segment of the market (affordable multi-family dwellings), while developing procurement processes that will not be too alien to clients.

Spiceley says: ŌĆ£You have to fit with current procurement methods. You can be as innovative and as challenging as you want, but if youŌĆÖre not conforming with the way people procure, youŌĆÖre going to find it difficult to get your product, whether its physical or digital, out to the market.ŌĆØ

Hartiss agrees, adding that the simple steel kit of parts and the focus on affordable multi-family residential will provide a solid foundation on which to build. He says that the software has been built to allow organic expansion for the companyŌĆÖs product range, so that they can eventually introduce new materials such as timber or building typologies outside of their residential base. ŌĆ£All of that can go in there as well and suddenly we are starting to broaden the appeal of the thing from a fairly sort of controlled beginning,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£What we have done [to begin with] is to really focus on the stuff that we think we can deliver really well.ŌĆØ

The firm closed its ┬Ż10m series A funding round last September, raising money from venture capital funds, including Blackhorn Ventures, GroundBreak Ventures, Goldacre and Leela Capital, as well as UK developer Regal London, the venture capital arm of building material giant CEMEX and SFV, a venture capital fund backed by German real estate firm Patrizia.

Spiceley says RegalŌĆÖs involvement in particular makes ŌĆ£a huge differenceŌĆØ for the firm and says the real estate business sees Modulous as being ŌĆ£almost like the spine of their operations, because weŌĆÖll be involved right from the beginning, using the digital tool to help support their land buying, through the design iterations until the final delivery on site.ŌĆØ

The company is looking into creating a ŌĆ£Regal versionŌĆØ of TESSA, with floorplans and pre-loaded metrics embedded in the software and may eventually do the same with other clients.

The business believes its asset-light business model will allow it to be globally scalable ŌĆō it has already opened a US office in Seattle, led by alumni of the doomed modular firm Katerra, and is exploring a partnership in Canada. One of its founders is based in Vienna and is looking at the German-Austrian market, which it views as a good fit.

But Spiceley is keen to emphasise the importance of going steady. ŌĆ£We wouldnŌĆÖt want our name associated with, you know, some people using the stuff recklessly or incorrectly across the world, he says. ŌĆ£ThatŌĆÖs what people are paying for from us ŌĆō the governance of the delivery of design and construction of these thingsŌĆØ.

If youŌĆÖre not conforming with the way people procure, youŌĆÖre going to find it difficult to get your product, whether its physical or digital, out to the market

Chris Spiceley, client accounts director, Modulous

Back on home turf, modules will be landing on site for its first physical development later this year. The 12-home Romney Avenue scheme for Bristol City Council, developed without the aid of TESSA, will provide proof-of-concept for the firmŌĆÖs physical solution. Modulous was brought onto the project ŌĆō originally designed by AHR Architects ŌĆō to adapt it for offsite construction. The firm estimates that its solution will enable 50% time saving on delivering the project, as well as a 60% reduction in embodied carbon and 70% reduction in construction waste.

The business theory behind Modulous is simple: build a good, reliable product that people want and give it to them in a way that is easily slotted into their processes.

For so long, modular and offsite construction has been the future that never quite arrived ŌĆō theory failing to become practice. It may be too much to say that this year is make of break for Modulous, but as it makes its push for financial freedom, anyone with an interest in the future of construction should keep a close eye on the business in 2023.

Expert view:

Mark Farmer on successful MMC models

ThereŌĆÖs no doubt that the capital-intensive nature of setting up a turnkey manufacturing led platform is not for the faint hearted. To get it right requires time and money. Success will require the evolution of a market aligned and attractive product, a scalable and technology-enabled design and manufacturing strategy. It also relies on a sound commercial and delivery model hard wired to end-user demand in what is a notoriously change-resistant market. Failure on any one of those criteria will usually end in overall business failure, some of which we have seen in 2022 and unfortunately, we will see more.

To avoid the high risk of owning the means of production, businesses like Modulous are understandably looking at asset light approaches where they become enablers of a similar outcome but using a digital platform to connect different stakeholders together that already have the means to design, manufacture and integrate into a final site-based solution.

The theory is solid and if such approaches can overcome the lingering resistance to change that still prevails across the industry, then we will no doubt see a proliferation of what I call distributed digital manufacturing approaches alongside some of the higher profile and centralised turnkey modular operations that dominate the headlines.

The primary issue is the initial journey of getting to scale as a digital product platform operating in a market where manufacturing economies are so important and the danger is slicing the digital product platforms cake into thinner and thinner slices. As Chris Hartiss rightly says, you need to have a model that can be procured in a conventional way and it also needs to be cost competitive.

Success with this and other MMC models still relies on a client leading from the front

We will never get away from the cost sensitivity that prevails in the industry and thinking that you can sell at a premium because it is quicker or better quality is a dangerous assumption to make. The ability to reduce costs must stem from process and physical waste reduction and must also factor in whatever commercial return model the digital platform itself is working to.

For me, success with this and other MMC models still relies on a client leading from the front, hence the need for the likes of Regal London, as referenced in the Modulous case study, to adopt MMC as part of their own development strategies. It also needs the key advisers and delivery stakeholders ŌĆō designers, quantity surveyors, contractors etc ŌĆō being directed by the end client to engage with such platforms, not seeing this as a threat to their fees or project role and showing a willingness to re-educate themselves on new technical solutions, costs and site logistics. This adviser and constructor inertia has been as much of a barrier to wider MMC adoption as anything I have seen over the last few years.

The other key dependency is ensuring any such distributed digital platform solutions can be delivered in the real world with appropriate end product accreditations including warranties and insurance that bind the manufactured and site constructed elements into a fully assured composite project. If you canŌĆÖt address this point, you do not have a mainstream solution, whatever form of modularisation you are proposing and however many of the issues I raise above you are able to address.

Mark Farmer is chief executive of Cast Consultancy, author of the Modernise or Die report and government champion for MMC in housebuilding

Expert view:

Martha Tsigkari on the challenges of manufacturing processes

Modular housing has always been an exciting proposition albeit with some very interesting challenges. Parameters such as variation and adaptability, contextual and environmental appropriateness, a rich kit-of-parts, and ease of design and procurement can drive a successful solution.

Many offsite start-ups in the architecture, engineering and construction (AEC) space have been trying to investigate the idea of modular housing through a vertically-integrated process, which has proved tricky. The fundamental problem is that a building is not a product: you cannot devise an end-to-end, all-encompassing manufacturing process for the AEC industry as you would for a smaller product such as a phone.

The fundamental problem is that a building is not a product

Any modular system needs to respond to different typologies, geographical locations, environmental concerns, and structural and planning requirements (to name a few) that make it impossible to develop an end-to-end process that can cater for all these different programmatic, construction, contractual, cultural and environmental requirements. Such an endeavour would require a kit-of-parts and a supply chain so expansive, that it becomes virtually unmanageable.

Katerra* was unsuccessful in their endeavours because of these very challenges, and it will be interesting to see how Modulous will tackle these issues, both in terms of their bespoke software to facilitate design optioneering, as well as its integrated supply chain model. In terms of the former they either have to create a very focused, and by extension restrictive, product that can cater for a particular building typology/geographical location or try to focus on developing a highly adaptable offering that takes into consideration the complexities of the AEC industry but can become difficult to manage and to financially support. For their supply chain, they are seemingly shying away from acquisitions and focusing more on supply-chain partners, which can hopefully resolve issues of merging and ŌĆō more importantly ŌĆō integrating multiple independent companies under one umbrella.

*Katerra was an tech-driven, US offsite startup which collapsed in 2021 after burning through more than $2bn in funding.

Martha Tsigkari head of applied research and development at Foster and Partners

║├╔½Ž╚╔·TV the Future Commission

The ║├╔½Ž╚╔·TV the Future Commission is a year-long project, launched to mark ║├╔½Ž╚╔·TVŌĆÖs 180th anniversary, to assess potential solutions and radical new ways of thinking to improve the built environment.

The major projectŌĆÖs work will be guided by a panel of 19 major figures who have signed up to help guide the commissionŌĆÖs work culminatuing culminate in a report published at the end of the year.

The final line-up of commissioners includes figures from the world of contracting, housing development, architecture, policy-making, skills, design, place-making, infrastructure, consultancy and legal.

The commissioners include Lord Kerslake, former head of the civil service, Katy Dowding, executive vice president at Skanska, Richard Steer, chair of Gleeds, Lara Oyedele, president of the Chartered Institute of Housing, Mark Wild, former boss of Crossrail and chief executive of SGN and Simon Tolson, senior partner at Fenwick Elliott. See the full list here.

The project is looking at proposals for change in eight areas:

- Skills and education

- Energy and net zero

- Housing and planning

- Infrastructure

- ║├╔½Ž╚╔·TV safety

- Project delivery and digital

- Workplace culture and leadership

- Creating communities

>> EditorŌĆÖs view: And now for something completely positive - our ║├╔½Ž╚╔·TV the Future Commission

>> Click here for more about the project and the commissioners

║├╔½Ž╚╔·TV the Future will also undertake a countrywide tour of roundtable discussions with experts around the regions as part of a consultation programme in partnership with the regional arms of industry body Constructing Excellence. It will also set up a young personŌĆÖs advisory panel.

We will also be setting up an ideas hub and we want to hear your views.

>> Email buildingfuturecommission@building.co.uk to get in touch

1 Readers' comment