The Builder makes an ascent up the 鈥渧ast bones鈥� of the half built bridge, the scale of which astonished the engineering world at the time

Below are three pieces published in The Builder charting the construction of the Forth Bridge. The first is a news item on some early proposals, the second a visit to the construction site and the third a reflection on the finished bridge. The vast structure, nearly 2.5km long, was one of the greatest engineering achievements in human history when it was completed, a point widely acknowledged at the time. One subsriber to The Builder wrote in to describe how it made classical edifices beloved by the Victorians, like the Pantheon in Rome, 鈥渓ook like toys鈥�.

Its scale was recognised years before it started construction, when early plans by Thomas Bouch were backed by Parliament. This version was never built - it was abandoned after the collapse of Bouch鈥檚 Tay Bridge in 1879, which killed 75 people and ruined the engineer鈥檚 career. But despite The Builder鈥檚 astonishment at the size of Bouch鈥檚 proposals for a bridge which was 150ft high with a 1550ft widest span, the bridge that was eventually completed by John Fowler, Benjamin Baker and William Arrol was far larger - its longest span was 1,700ft and it was more than double the height, at 360ft.

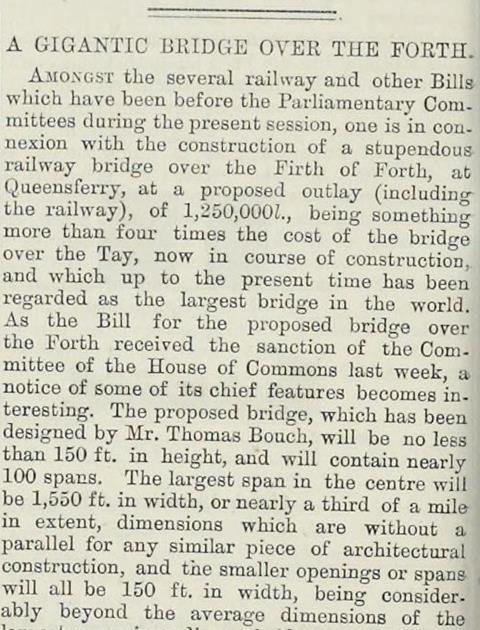

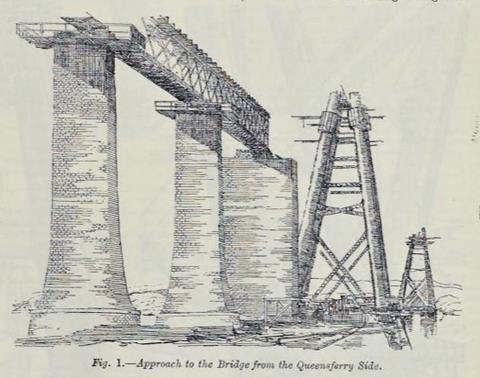

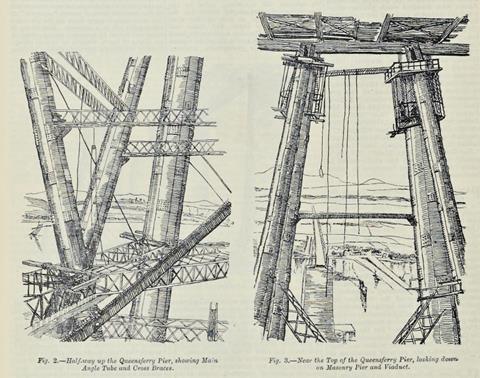

A reporter from The Builder visited the construction site in 1887 after concluding that 鈥渓ife was not worth living without seeing the Forth Bridge鈥�. Sketches from the visit accompany the piece, showing views of the site and from inside the web of giant cantilevered girders being erected on the piers. The unnamed reporter made an ascent up the bridge鈥檚 鈥渧ast bones鈥�, describing the 鈥渃urious and picturesque鈥� effect of moving through such a large structure.

When it was opened in 1890, The Builder simply concluded that the bridge was one of the 鈥漡reatest and boldest engineering projects in the history of the world鈥�. The piece says: 鈥淲hether the construction of the bridge will repay in a financial sense the outlay upon it may be doubtful, but we are disposed to agree with the opinion we have already seen expressed, that it was worth doing for the sake of glory, and the exhibition of the power of modern engineering to cope with great natural obstacles.鈥�

好色先生TV item in The Builder, 14 June 1873

A GIGANTIC BRIDGE OVER THE FORTH.

Amongst the several railway and other Bills which have been before the Parliamentary Committees during the present session, one is in connexion with the construction of a stupendous railway bridge over the Firth of Forth, at Queensferry, at a proposed outlay (including the railway), of 1,250,000l, being something more than four times the cost of the bridge over the Tay, now in course of construction, and which up to the present time has been regarded as the largest bridge in the world.

As the Bill for the proposed bridge over the Forth received the sanction of the Committee of the House of Commons last week, a notice of some of its chief features becomes interesting. The proposed bridge, which has been designed by Mr. Thomas Bouch, will be no less than 150 ft. in height, and will contain nearly 100 spans. The largest span in the centre will be 1,550 ft. in width, or nearly a third of a mile in extent, dimensions which are without a parallel for any similar piece of architectural construction, and the smaller openings or spans will all be 150 ft. in width, being considerably beyond the average dimensions of the largest spans in ordinary bridges.

The highest engineering evidence on the design was laid before the Parliamentary Committee, and amongst the engineers of eminence who bore testimony in favour of the proposal, were Mr. G. P. Bidder, Mr. Hawkshaw, Mr. Barlow, and Mr. Harrison, all of whom deposed as to the practicability of its construction, the sufficiency of the estimates, and as to its safety and suitability for carrying railway traffic. On these points, a joint report, signed by all the above-named engineers, was laid before the Committee, in which they state that having examined the plans of the proposed bridge, in connexion with storms of wind, as well as the effects of passing loads over it, and also in regard to temperature, they all agree in being satisfied that the bridge, when completed according to the designs and dimensions, and with the materials submitted to them, will be found amply sufficient not only for the safety of the ordinary traffic, but also to meet the strains due to extreme gales of wind.

As to construction, the engineers in question state that the most important point is the sufficiency of the foundation and anchorage, and in reference to that question the information afforded them gives them complete confidence; whilst having regard to the varied and powerful means which are now at command for the erection of such structures, they believe that the execution of this bridge, although of unusual magnitude, is quite practicable, and capable of being carried out with success by modern skill.

Excerpt from report on visit to Forth Bridge construction site, 16 July 1887

Proceeding till we get under the pier, we at last realise the size of the thing we have come to look at. The space included within the four angle piers is quite a large area, crammed, of course, with all the d茅bris of builders鈥� operations, while here and there a red flag warns people off places which are dangerous, owing to the chance of falling bodies from work going on above. The angle tubes go up like leaning towers into the air. Above there is a complicated mass of wind-braces, scaffolding, and tackle, which obstructs the view to the top, and prevents one taking in the whole.

We can go up very expeditiously, however, in one of the two travelling-cages which work with guides on a couple of steel ropes stretched till they are rigid: the cage being drawn up a rope wound by a steam-engine below, and fitted with a patent clip warranted to hold on the guide ropes if the suspender breaks. The ascent between these vast bones, so to speak, of the structure, is curious and picturesque in effect. In sketches 2 and 3 we give reminiscences of the effect of the structure as seen from two points on the temporary ladders fixed on the wind bracing. They are both looking towards the Queensferry side of the Firth, and will perhaps give some idea of the look of things up here, and the appearance of these great tubular girders soaring up into the air. No. 2 is taken just at the half-way point, where the great cross-braces at the side intersect; No. 3 is about 60 ft. or 70 ft. perhaps from the top, and in this is shown the masonry pier before mentioned, far below, and reduced to a very secondary position. At the upper part of this sketch are seen two of Mr. Arrol鈥檚 鈥渃ages鈥� clinging round the tubes.

Arrived at the top, we find ourselves on a broad scaffolding covering nearly all the space included between the members of the pier; from this there is a glorious view over the Firth and the adjoining country; and, which is more to the purpose, from this point we can realise better than anywhere else the nature of the undertaking. Let the visitor bear in mind that he is here 350 ft. above sea level, on the top of a construction of immense proportions and enormous weight; let him look out at the next pier, the Inchgarvie pier, a third of a mile off; and let him reflect that from the erection he stands on, a construction equally massive and heavy in its parts, and nearly twice as long, is to be built out horizontally into mid-air over the sea, without any possibility of scaffolding, by men working in squirrel cages stuck on to the end of the tubes, and pushed on as the tubes are built, and he will probably agree with us that this is an engineering project calling not only for scientific knowledge and experience, but for no little courage, on the part both of engineer and artisans.

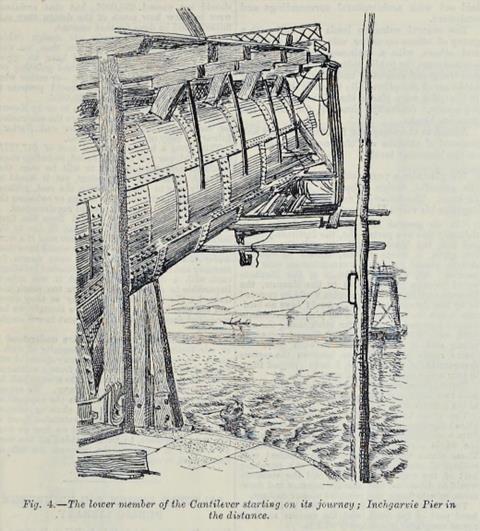

A vivid idea is given of the nature of this part of the work by the appearance of the portions of lower members of the cantilevers already finished, as shown in sketch 4, taken from the top of one of the four circular granite piers which form the base of the steel pier. Here the portion of the cantilever tube which is completed is shown projecting out into mid-air like the bowsprit of a huge ship, with the workmen鈥檚 cage at the end of it; and in that way and by that means it is to be carried on. (At the time of the sketch being taken the cage was not being used, and the netting had been removed, leaving only the frame-work.)

The cantilevers at opposite sides of the main pier are, of course, carried on simultaneously, in order to balance each other, and the plan is to commence with the lower member of the cantilever; then to sling it up temporarily and execute an equal length of the top member and the cross braces which connect the two; this section of the cantilever will then be complete and stable in itself, and the next section can be proceeded with in the same manner. The temporary supports for the lower members are in themselves of a tolerably permanent kind, and at the time of our visit 鈥渢emporary鈥� slings were being adjusted for this purpose, which, it may be mentioned, were formed from some of the links of Old Hammersmith Bridge, which have come in very usefully, and seem to be in very good condition.

We asked one question at headquarters which we thought a crucial one, and the answer to which we promised to keep a secret if desired, viz., how long do the engineers, in their inner conscience, believe that an enormous iron structure like that, with such an outer and inner area of plate surface, will last? Mr. Baker, however, has every faith in it from that point of view; he is of opinion that, properly looked after, there is no reason why it should not stand for 500 years. Provision has been made for getting at every part of it; there are manholes in every tube and in the diaphragms throughout them, and steel ladders formed in the interior of the tubes. It is to be hoped air inlets have been provided also; it would be rather a stupid kind of death to be stifled at the top or bottom of a long tube.

The cantilevers are only just commenced and there is no doubt this is the most difficult and anxious part of the work; but we anticipate its successful accomplishment. It will, no doubt, be objected by some that the bridge is a very ugly erection; that was our own impression the first time we saw a sketch of the design. But the fact is that you do not feel this after seeing the work itself. It is so immense that it fascinates by its very size, and so difficult an undertaking that one feels that decorative considerations would be out of place; the problem is to do it at all. Every architect who is in the way of doing so should see this extraordinary work. He may not think it beautiful, but he will probably come away with the conviction that Gothic vaults were not such very big things after all.

Article, 8 March 1890

NOTES.

We have said so much concerning the Forth Bridge at various stages of its progress that it is hardly necessary now to recapitulate its history, or to do more than offer our congratulations to those most nearly concerned on the successful completion of one of the greatest and boldest engineering projects in the history of the world. Whether the construction of the bridge will repay in a financial sense the outlay upon it may be doubtful, but we are disposed to agree with the opinion we have already seen expressed, that it was worth doing for the sake of glory, and the exhibition of the power of modern engineering to cope with great natural obstacles.

Sir John Fowler, we are glad to see, is to be created a Baronet, and Mr. Baker a Knight Commander of the Order of St. Michael and St. George, and Mr. Arrol, the contractor, will be knighted. No one will dispute that all the honours are well earned, far better than some of the similar honours that are bestowed as mere political rewards. Sir John Fowler in his speech at the luncheon did not forget to say a word for the workmen, who as a body deserve all recognition for the courage as well as skill which they have exhibited in carrying out this difficult and risky work. To say that 鈥渘ot one of them had ever knowingly scamped a rivet鈥� may be hardly in accordance with things we have both heard and seen in the progress of the work; but this suppose is an occasion on which 鈥渙mnes omnia bona dicere鈥� is a kind of accepted understanding.

More from the archives:

>> The clearance of London鈥檚 worst slum, 1843-46

>> The construction of the Palace of Westminster, 1847

>> Benjamin Disraeli鈥檚 proposal to hang architects, 1847

>> The Crystal Palace鈥檚 leaking roof, 1851

>> Setbacks on the world鈥檚 first underground railway, 1860

>> The opening of Clifton Suspension Bridge, 1864

>> Alternative designs for Manchester Town Hall, 1868

>> The demolition of Northumberland House, 1874

>> Dodging falling bricks at the Natural History Museum construction site, 1876

>> First proposals for the Glasgow Subway, 1887

No comments yet