Timber-frame buildings鈥� reputation has been through the mill recently. But one international team has a vision for wooden structures that reach to the sky. The only thing now is to make sure they don鈥檛 burn down

Multistorey timber-frame buildings have come under a lot of scrutiny lately. There have been two big fires on half-built timber-framed structures in south London in the past six months, which have prompted a Greater London Authority inquiry. Insurers are increasingly concerned about the rising costs of claims associated with timber frame.

All these recent incidents have been in buildings of six storeys or less, for the simple reason that the available technical guidance only covers buildings up to that height. The picture abroad is similar; for example, in Switzerland timber frame is limited to six storeys and in Germany most timber-framed buildings are under 13m.

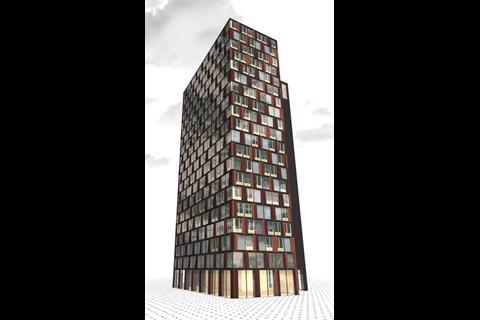

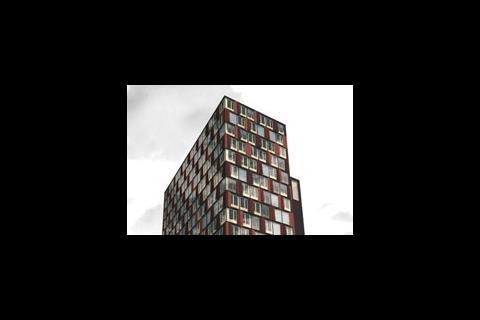

So it comes as something as a surprise to discover that a consortium is developing a 20-storey, timber-frame tower. This isn鈥檛 some student experiment, but a serious research project set up with a view to constructing a real building. The consortium consists of Austrian developer Rhomberg and architect Hermann Kaufmann, timber frame manufacturer Wiehag, Graz technical university and engineer Arup. Rhomberg wanted to develop a more environmentally friendly alternative to concrete or steel-framed towers. Called LifeCycle Tower, the building the team is working on is a modular, prefabricated solution that should be suitable for offices, flats and hotels.

Before the project gets to the commercial stage there are questions to answer 鈥� principally: how will it stand up and what happens if it catches fire? Arup is responsible for the technical design of the building. 鈥淭he big question is, is it possible from the technical point of view?鈥� says Karl Wallasch, fire engineer with Arup. 鈥淭he main challenges are structure and fire. Acoustics is an issue, but something we can deal with.鈥�

The team has developed a concept that will look familiar to anyone versed in tall building design. The 20-storey structure is 70m high, 43m long and 27m wide. It sits on a two-storey concrete base and, like all good towers, has a central core, whose 18.9m long and 8.1m wide dimensions leave plenty of lettable floor space. The building has perimeter columns spaced at 2.7m intervals and the floors are constructed from a concrete deck with beams underneath.

The big question is, is it possible from a technical point of view? the main challenges are structure and fire

Karl Wallasch, Arup

The big difference is that the core, perimeter columns and floor beams will all be wooden, with the floors a composite design of a 160mm concrete slab with a timber downstand beam. These beams don鈥檛 span fully between the perimeter columns and the core as they are intended to stop the floors sagging in the middle.

Unsurprisingly, these timber elements will all be glulam 鈥� strips of wood glued together to form long, strong and stable beams. This is the only way to create beams of sufficient structural strength. The core walls will be made from vertical glulam beams 240mm thick and 30m long. Up to 10 beams are fixed together to form a panel using glued-in metal fixings. These panels are then joined together at each end via steel plates which transfer the vertical shear forces while at the same time allowing horizontal movement that might arise from shrinkage of the timber. The perimeter columns are made using glulam sections of 480mm by 250mm, and 200mm deep glulam beams will be used for the floor.

Glulam may be structurally up to the job, but what about its fire performance? Wiehag makes the glulam beams and a third-party laboratory in the Czech Republic has carried out extensive tests on their fire performance 鈥� Arup says the concept of using the timber consultancy meets Austrian fire regulations, which say the structure must resist the effects of fire for at least 90 minutes.

The key is the size of the beams. Timber burns from the outside and it would take a long time for enough timber to burn away from the edges to affect the beams鈥� structural performance. Timber burns at a rate of 0.6-0.7mm/min and so, for 90 minutes of resistance, a 63mm sacrificial layer of timber has been designed into the overall dimensions of the columns. A layer of fire-resistant material is also sandwiched between this sacrificial layer and the central load-bearing element of the timber column.

Like any building, the LifeCycle Tower had to be engineered to prevent fire spread. It will be protected by sprinklers and sophisticated fire detection systems. Cavities that could contribute to hidden fire spread have been eliminated 鈥� for example, the floor beams will be on show. Non-flammable materials will be used for the facade and the idea of perching the building on a two-storey concrete base is to reduce the risk of arson at street level.

Non-flammable materials will be used for the facade, and the two-storey concrete base will reduce the risk of arson at street level

In addition, when the tower is built the concrete decks will span the entire floorplate so the perimeter columns on each floor will always be separated by the 160mm-thick layer of concrete. The core is made up from continuous lengths of glulam beam and will be clad by three layers of gypsum board, totalling 51mm thick, to provide 90 minutes of fire protection and to allow a safe escape route. Two staircases will be provided in the core and these will be pressurised to stop smoke ingress.

What about the risk of it catching fire while under construction? Because it has been designed as a prefabricated solution, the tower should be quick to build, which reduces the risk. Fire spread is also reduced by the big section glulam beams, which are inherently more fire resistant than the small section timber used for most housing. Indeed, much of this timber will be left exposed in the completed building. Arup says it recognises the risks while under construction. 鈥淎nything that is done on site will be subject to a very high quality management system,鈥� says Wallasch.

Although the plans for the tower sound good in principle, Arup says it will need to be thoroughly tested. The next stage is to fire-test actual construction details to see how well the building might perform. After that, a three-storey prototype will be built to further test the fire performance and to check the structural design.

But the process will be a long one. It鈥檚 unlikely the first building would start construction until 2011. Even if that is a success, should the team want to bring the design to the UK, it would have to be modified to meet our regulations, principally our tougher, 120-minute fire resistance rating for structures. According to Carsten Hein, project leader at Arup, this should be relatively straightforward. Given the rate at which timber burns, an extra 30 minutes of protection could be provided by designing the timber sections with an additional 18-21mm of material in the sacrificial layer on each side. On top of this, an extra 18-21mm thick sheet of gypsum board would provide the necessary protection to the core walls.

It may be some time before we see timber-framed high-rises in the UK. But with concerns growing about the environmental impact of materials, this technique could yet usher in a new era for timber frame.

No comments yet