Elisabeth Selk of Arcadis explores the opportunities for infrastructure delivery in the UK to dive into deeper pools of private finance

01 / Overview of the infrastructure investment challenge

Investment is needed

Infrastructure in the UK needs both overhaul and expansion. Successive governments have addressed the challenge of raising investment from a range of public and private sources. With the Labour Party now considering an expansion of the role of the public sector in utilities provision, investment is the subject of a lively debate.

The government鈥檚 current National Infrastructure Delivery Plan (NIDP) sets out plans for 拢500bn worth of investment in energy, transport, flood defence, waste, water and communications, so there will be plenty of opportunity for investors 鈥� whether directly in projects, or in government borrowing raised to finance infrastructure delivery.

The results of the CBI/Aecom Foundations for Growth survey published on 25 October show how critical it is that government sharpens its focus on delivery as part of its Modern Industrial Strategy. Similarly, the National Infrastructure Commission鈥檚 (NIC) interim National Infrastructure Assessment released on 13 October highlighted the need for a significant increase in investment to tackle the three Cs of congestion, capacity and carbon.

The requirements for infrastructure investment have two components:

- Finance is the short-term investment associated with bringing a project to market, construction and commissioning. Finance is typically provided by government, banks and 鈥� increasingly 鈥� private equity. Depending on the stage of a project, finance is exposed to a wide range of potential risk, which affects the desired rate of return and the contingencies built into overall pricing.

- Funding is the return to investment paid by the asset鈥檚 income stream. Long-term funding investment typically comes on board once the asset is operational through a process of recycling of capital. Operators are exposed to risks associated with operating costs and usage levels, but these are easier to predict than the project risks.

The overall costs of finance form a very significant share of the lifetime cost of infrastructure assets. As a result, any measures that can be taken by the project sponsor to reduce cost 鈥� either by increasing competition or by sharing risk 鈥� has a significant impact on the cost to the consumer.

However, the investment profile means that while pension funds and insurers participate in long-term funding, they look for more entrepreneurial project delivery organisations to share the risk. Seasoned specialist infrastructure investors such as InfraRed, DIF and Infracapital can for example accept more development and construction risk on behalf of their institutional investor clients. The commissioning of new standalone infrastructure including offshore wind has combined both sources of finance in a competitive auction process. This is starting to deliver increasingly competitive results, with the most recent auction for offshore wind delivering 3.2GW of capacity at guaranteed prices that are 47% lower than were offered in auctions nearly three years ago.

Government initiatives

The CBI survey points to the government鈥檚 pipeline of projects, its Clean Growth Strategy and the initiatives announced at the 2016 Autumn Statement as welcome indications of a sustained commitment to infrastructure that goes beyond the pipeline set out in the NIDP. These government initiatives include the following:

- Establishing a National Productivity Investment Fund (NPIF) to provide 拢23bn of additional spending, which includes almost 拢11bn of extra economic infrastructure and housing investment over the period 2017-21.

- Extending the 拢40bn UK Guarantees Scheme to 2026. The scheme reduces borrowing costs, improving the viability of infrastructure projects such as the Northern Line Extension and Hinkley Point.

- Announcing a new pipeline of projects with a focus on social infrastructure through the Private Finance 2 (PF2) initiative.

Role of the private sector

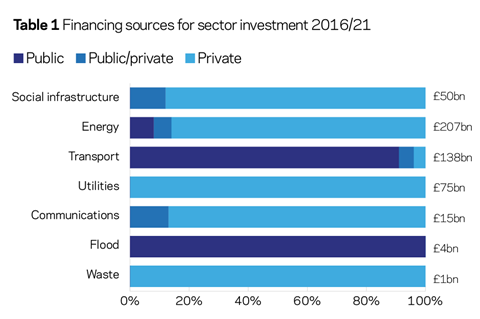

The programme set out by the NIDP requires almost 60% of investment to be financed by the private sector. Almost all energy generation, utilities, waste and communications investment is privately sourced and delivered into regulated markets. As demand for investment grows, one test for government and regulators is to leverage capital into riskier and more expensive investment opportunities. Initiatives such as Direct Procurement, which sets out to introduce new investor-led consortiums for the delivery of new, privately managed infrastructure are being promoted by regulators such as Ofgem in the offshore transmission market.

The 2017 NIC needs assessment included a review of the private infrastructure finance market. The main findings of the report are:

- The level of private finance has returned to pre-financial-crisis levels 鈥� with a particular focus on deals in the renewables sector.

- Banks remain the most important source of funding, and UK pension funds have a lower level of participation than in some markets 鈥� this is partly because of the fragmentation of the UK pension fund sector.

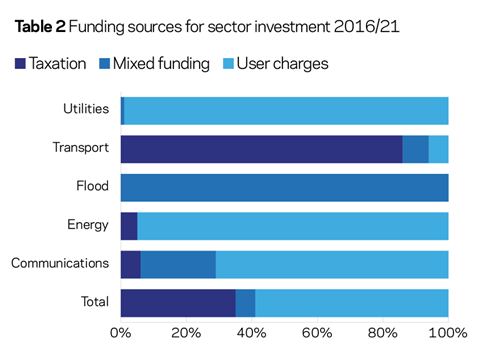

- Projects with a reliable income stream related to a user charge are readily financeable, leaving schemes that cannot be funded by a user charge model to rely more on public investment (for instance, transport).

- The key factor to attract a flow of new investment into UK infrastructure is to have a pipeline of similar projects with similar funding models and risk profiles 鈥� enabling bid costs to be spread across a portfolio.

- Government鈥檚 prime role is to provide confidence through a strong policy framework and by ensuring security of investment. Additional support is typically required on a case-by-case basis.

Investable programmes

The key to unlocking capital from the private sector is in making projects more investable. This can be summarised in simple terms as building a clear value case 鈥� focused on the income streams that provide the funding source, including their value, timing and risk profile 鈥� and determining the risk profile. This concerns the scale, duration and complexity of the project, specific delivery and operation risks and any dependence on third-party performance.

The experience gathered from large infrastructure projects points to specific risks faced by investors in the sector, specifically:

Development risk: Development and construction risks in infrastructure are very significant, requiring large upfront outlays of capital expenditure with no income stream and no collateral in the asset. Development is subject to complex arrangements of assurance and control management.

Demand risk: Revenues tend to accrue once a project is operational 鈥� creating an expensive funding gap. On more risky projects, revenue streams remain uncertain, hard to quantify or hard to price. Some energy-from-waste (EfW) projects have failed to meet revenue targets, for example, due to operational problems.

Balancing affordability and service quality on one side and deliverability and profitability on the other represents a significant challenge for government, regulators and public-sector clients as they seek to develop investable solutions to the UK鈥檚 growing infrastructure needs.

The risk profile can be mitigated through the sharing of risk exposure or through insurance. The way the projects are structured has a significant impact on risk allocation and on the cost of finance. The Thames Tideway Tunnel project is a notable example of a highly complex programme that was structured from the outset to attract long-term equity investors including pension funds and insurance companies. This is discussed further in a case study.

Broader availability of investment opportunities will make investing in UK infrastructure more attractive. The onus is on the government to develop a substantial pipeline of well-defined projects for tender.

This will considerably contribute to lowering the cost of finance by increasing competition among investors.

Sources of financing

The private sector typically raises funds for investment in infrastructure assets from two sources:

Corporate finance: A sizeable proportion of investment will be raised through corporate finance secured against company balance sheets. This is particularly the case in regulated sectors, including water and energy networks. Corporate funding costs have fallen significantly following the global financial crisis, and many infrastructure businesses have been successful in recycling their capital during this period.

Project finance: Project finance is riskier, because there is at best only limited recourse to a balance sheet as security. The shareholders rely on the project鈥檚 revenue generation, while lenders need to be satisfied that the project cash flow will provide for the repayment of the debt service. Equity investors are typically institutional investors (pension funds or insurers) or publicly traded infrastructure funds. Sovereign wealth funds have also been active participants. Lenders include commercial banks, multilateral agencies, such as the European Investment Bank (EIB) and specialist institutions, including the Green Investment Bank (GIB).

Since the global financial crisis, investor risk appetite has increased because of the low rates of return offered by traditional low-risk assets such as government bonds. However, short-term finance is expensive, and a lower cost of capital can be achieved if long-term equity investors can be involved at the outset of a scheme.

02 / The UK鈥檚 ambitious investment plans

The World Economic Forum ranks the quality of the UK鈥檚 infrastructure 11th globally, with a downward trend, largely because of transport. The UK government has committed to a major investment plan with the National Infrastructure Delivery Plan and it faces significant pressures to accelerate the pace of delivery. Only 20% of businesses and 26% of the public in the UK are happy with the pace of improvement, according the 2017 CBI/Aecom Foundations for Growth report.

The National Infrastructure Commission鈥檚 initial needs assessment, released in October, which forms part of its 30-year assessment of the UK鈥檚 infrastructure needs, highlights the current state of congestion and capacity shortages:

- The UK lags behind countries including the US, the Netherlands and Japan on 4G and broadband

- Between 2012 and 2015, speeds on inner London roads fell by 9%

- Overcrowding on rail services during peak times in London increased by 45% between 2011 and 2016

- More than 60% of the UK鈥檚 power stations will need to be replaced to meet carbon targets.

The report highlights the scale of the task required to tackle the three Cs of congestion, capacity shortages and the carbon economy.

Despite the challenges highlighted by these last assessments, real progress is being made. UK infrastructure will shortly benefit from major capacity investments including Crossrail, the Great Western electrification project and the ongoing smart motorways programme. Large volumes of private investment have poured into renewable energy generation, in particular offshore wind, such as E.on鈥檚 拢1.3bn investment in the 400MW Rampion development.

03 / The role of risk allocation in attracting private investment

Infrastructure is a booming sector for investment. Recent transactions associated with Thames Water and the National Grid highlight that there is plenty of interest in UK infrastructure businesses that benefit from transparency, a stable regulatory regime and strong investor protection.

Upfront capital investment in development is a different matter. Institutional investors, pension funds and insurance companies, are less well equipped to assess, price and accept the elevated delivery risks of large, one-off infrastructure projects. Project risks are usually bifurcated between the construction (when most defaults occur) and operational periods of the project.

The public sector has traditionally provided the bulk of investment in high-risk programmes such as roads, rail, and flood prevention. Looking forward, private finance is expected to contribute almost three-fifths of the National Infrastructure Delivery Plan 鈥� either through established channels such as the regulated utilities, or through special purpose vehicles (SPVs), the companies set up to deliver new infrastructure. Projects that are currently on offer via the NIDP are riskier and more complex than many of the smaller-scale and less risky social infrastructure projects the market grew comfortable with financing before the global financial crisis.

Even though institutional investors tend not to invest in construction risk, investment can be funded competitively. Massive transport PPP programmes have, for example, been successfully implemented in France and Benelux, with healthy competition and good value for money for the public. These demonstrate that such assets can be delivered at a competitive cost of capital and can offer more attractive, higher returns than regulated utilities. The provision of infrastructure ultimately benefits from the private sector providing better value through the whole life cost approach and intelligent lifecycle management of transport infrastructure assets.

Effective and innovative risk allocation and mitigation enable greater access to private finance, both in terms of equity and loan finance, providing for an optimum lifetime cost of capital. For this to occur, the allocation of risks within the SPV and to different partners associated with the investment is an essential condition for deliverability.

Table 3 (below) lists several of the potential risks in infrastructure projects and their key mitigants.

| Design/construction phase | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Project design |

Planning issues, design versus user requirements, lack of system integration, delayed construction permits |

Streamlined planning and centralised procurement |

|

Best delivery practice, eg procurement route map |

||

|

Financing |

Cost and availability of financing and refinancing, counterparty and government-sponsored risk |

Multilateral agencies and/or export credit agencies, government guarantees |

|

Sponsor credit risk |

|

Lenders鈥� assessment of sponsor鈥檚 credit-worthiness |

|

Letters of credit sufficient to cover sponsor鈥檚 equity commitments |

||

|

Completion delay |

Project team expertise, complexity of project, long-lead equipment delays, project team solvency |

De-risked design and construction proposals |

|

Experienced, credit-worthy project team |

||

|

Liquidated damages to cover loss of revenues due to completion delay |

||

|

Availability of ancillary infrastructure |

Site availability (land acquisition, right of way), site quality (geological conditions, contamination), planning, operational constraints, availability of third-party infrastructure |

Risk transfers versus risk retention |

|

Penalty payments associated with infrastructure availability |

||

|

Cost overrun |

Equipment and raw material costs, labour costs, construction firm and subcontractor expertise, complexity of project, long-lead equipment delays |

Lenders鈥� technical consultant/audit to confirm adequacy of the project budget |

| Operations phase | ||

|

Performance and availability |

Operational efficiency, system underperformance, service interruptions, innovation risk |

Performance obligations specified in construction and operations contracts |

|

Experienced operator with a strong track record |

||

|

Long-term maintenance agreements, typically with the original equipment manufacturers |

||

|

Critical inputs (e.g. feedstock for energy generators) |

Raw materials availability, price and quality |

Long-term purchase agreement with a credit-worthy counterparty and agreed volumes/pricing |

|

Competitive arrangements |

||

|

Alliancing with suppliers |

||

|

Demand risk |

Lower demand and volumes than forecast, price elasticity, willingness-to-pay and affordability, policy change (such as subsidies) |

Offtake agreement with agreed volumes/capacity/pricing |

|

Independent market study, projects benchmarking |

||

|

Availability-based payments |

||

|

Demand-risk share agreement with sponsor |

||

|

Operations and maintenance |

Operational performance and wear and tear, labour and material costs, supporting infrastructure |

Long-term contracts if applicable |

| Across phases | ||

|

Political (including war, regulatory, planning) |

Lack of currency convertibility, changes in laws/regulations, expropriation, termination, breach of contract |

Risk-sharing with sponsor |

|

Currency and inflation |

Exchange rates, input cost inflation |

Risk-sharing with sponsor or matching financing |

|

Inflation risk mitigated through pricing mechanism |

||

|

Interest rates |

|

Hedging and recycling into long-term finance |

|

Force majeure |

Natural or man-made events e.g., earthquakes, flood, hurricane, civil war, riot, crime, strike |

Extensions of time and relief from liability |

|

Financial protection from insurers |

04 / The relationship between revenue streams and finance

As outlined in the introduction, availability of project finance is closely linked to funding 鈥� the revenue streams that can be set against whole life costs. The ability to raise sufficient revenues to cover running costs, maintenance, finance costs and investment returns is fundamental to the attractiveness and financial viability of infrastructure investment. Revenue sources include revenues from sales, direct user charging, public funds from taxation, or any combination of these sources. An example of this mismatch between revenues and development is that the 20-year private concession to run HS1 raised only 拢2bn of the estimated 拢6.2bn cost to the public sector of the construction of the line.

Mechanisms to manage uncertainty

To attract private investment, government has several mechanisms available to manage revenue streams to provide funding certainty:

- In the regulated utilities sector, investment has been attracted by a regulated asset base (RAB) model, which provides for a known rate return on the capital asset base as part of the pricing model. However, over time utilities have been subject to an increasing level of regulatory pressure to drive better outcomes aligned to improved outcomes, including customer satisfaction.

- The government offers very different strike prices for the nuclear and offshore wind sectors to mitigate for investors the distinct levels of associated risk. The investors behind Hinckley Point C remain, however, exposed to much greater project lifetime risks associated with the construction, operation and decommissioning of the power station compared with those investing in the offshore wind sector.

The very real risk faced by private infrastructure investors can be seen in the financial performance of assets such as the M6 Toll, which was sold to a consortium of Australian pension funds in 2017 following the restructuring of the original debt. While the M6 Toll never made a profit for its original investors, it is likely to be a very successful investment now that the income stream and funding have been realigned.

As more ambitious investment programmes are brought forward, the ability to access a wider range of long-term sources of funding is becoming ever more important. Crossrail, for example, has been partly funded by a charge on new commercial development, and the ability of public authorities to capitalise future business rate income is also playing a role in bringing forward new investment.

The ability to generate an income stream from the assets is constrained by market conditions, regulation, price elasticity and users鈥� willingness to pay. In many instances either there is no income (typically for roads), or the income provided by the asset does not cover the funding costs. Public-sector investment in taxpayer-funded public transport networks is a good example, although PPP mechanisms have been used widely by government to transfer delivery and operating risks to the private sector. Transport schemes can also be funded by availability-based payments, which will rely on government鈥檚 ability to structure the projects in a way that makes them suitable for private finance.

However, a challenge associated with public investment is that there might be private-sector beneficiaries of a project 鈥� landowners, for example 鈥� who will not have contributed to the cost and who are likely to benefit disproportionately.

Closing the gap between the income stream and the cost of funding 鈥� or securing contributions from a wider group of beneficiaries 鈥� form an increasingly important aspect of infrastructure finance, where part of the initial capital spend can be funded from other sources of income, such as land value capture or additional local taxation.

Land value capture

The concept of property or land value capture is based on evidence that infrastructure investment adds wider economic value, most often by increasing the value of the surrounding land or property. A variant of land value capture has been used in London, with the business rate supplement contributing to funding Crossrail. The mayor has proposed for Crossrail 2 a new levy on businesses, the mayoral community infrastructure levy 2 (MCIL2). The government has also introduced tax increment financing (TIF) schemes, based on the business rates retention scheme introduced in 2013-14. Under these schemes, local authorities may borrow for infrastructure projects, against the future growth in business rate receipts which will result from the projects. Transport for London, for example, has used the TIF model to finance the 拢1.2bn Northern Line extension to Battersea.

Table 4 (below) illustrates the main financing/funding models available for infrastructure projects. Getting the balance right between risk allocating, minimising cost of finance and the affordability of funding is an increasingly important aspect of the deliverability of a project.

|

Public |

General taxation |

Costs No additional costs to government for collecting taxes Size Large potential amount of funds available Equity Public-good infrastructure (such as water, flood defence) to be publicly funded Predictability With limited budgets projects must compete against each other |

Equity Some object to their taxes being used to fund localised infrastructure projects that will not benefit everyone (such as on HS2) Budget constraints These affect predictability 鈥� there is a risk that funding may be withdrawn and redirected to a new priority

|

HS2 (government borrowing for construction) to be ultimately paid out of general taxes Highways England RIS 1 programme

|

|

Private |

Revenues related directly to sales, user charges or access charges. These revenues may be supported by guarantees

|

Predictability Future revenues have some element of guarantee, which helps secure financing for risky projects Equity Those who use pay 鈥� user charging is not necessarily more regressive than other forms of taxation

|

Equity Those with lower incomes may end up spending a higher proportion of their incomes on charges. High charges can result in public opposition (energy prices) Politics User charges are not currently politically viable for many projects in the UK; there is reluctance to introduce more road pricing, despite the success of the London congestion charge |

Anglian Water 拢250m Green Bond issue (31 July 2017) to finance investments in its sustainability strategy Foreign investment to build Hinkley Point C nuclear plant underpinned by Contract for Difference and the UK Guarantees Scheme Thames Tideway Tunnel funded by charges levied by Thames Water |

|

Public/private |

Capturing additional income streams |

Equity Those who benefit from the new infrastructure pay for it; the amount government derives from these groups is proportional to the benefit they gain Size Some are optimistic that it could fund more projects and unlock financing

|

Size Future income streams are not enough to fund a project alone Appropriateness Not all regional bodies have the power to charge business levies; the potential for gains varies, being higher in urban and wealthier areas Complexity Value uplifts work differently in almost every case, so developing a generic arrangement is hard, and bespoke arrangements are expensive |

Crossrail 1 Community infrastructure levy in London Tax increment financing

|

05 / Opportunities to increase investability

With almost half a trillion pounds worth of infrastructure investment identified in the National Infrastructure Delivery Plan (NIDP), the UK government may well need to take further steps to encourage private-sector financing of infrastructure development.

The UK is well positioned to maximise investor participation in financing, and the profile of investment in UK infrastructure can be enhanced further with:

- A well thought-out and communicated strategic vision for infrastructure. The project pipeline set out by the NIDP includes repeat opportunities in sectors such as renewable energy that enable the development of standard solutions

- A stable and supportive regulatory and policy framework. Notwithstanding recent party political debate, the regulatory regimes for UK utilities are well established, giving investors a high degree of confidence.

- An attractive investor value proposition. UK infrastructure competes with other asset classes and jurisdictions for short-term and long-term finance. There are opportunities at project level to articulate the investor value proposition, which focuses on the dual objectives of ensuring a competitive risk-adjusted return for investors while delivering expected project outcomes.

- A critical mass of opportunity. The financial structuring of projects seeks to achieve optimum risk allocation between the partners. One way of achieving this outcome is to have multiple opportunities presented on the same basis. The renewables sector is achieving this critical mass. The World Economic Forum recommends governments should develop a standard methodology for allocating risks which will bring opportunities of scale.

- Mature approaches to risk transfer. A balanced approach to risk transfer should help to optimise the lifetime cost of privately financed programmes. For demand risk, this can include, taking steps to assure future revenue streams while maintaining competitive pressure 鈥� for example, Contracts for Difference (CfD) in the renewables sectors are driving competitive investment in low-carbon energy generation by reducing exposure to volatile wholesale prices. Government can take limited steps to reduce exposure to delivery risk 鈥� either by guaranteeing loans or by sharing some aspects of delivery risk 鈥� as is the case of Thames Tideway Tunnel.

- Growing institutional interest in infrastructure investment. The prospect of limited returns from low-risk investments is encouraging UK institutions including pension funds to be more proactive in their investment strategy. The development of cross-fund platforms that allow multiple funds to participate as investors in large programmes is an important enabler for expanded investment, as is the increased willingness of the public sector to share risk in project delivery.

Overall, the UK is well placed to continue to attract investment into well-constructed infrastructure investment vehicles. In the short term, loss of access to European Investment Bank funding may slow the closure of some deals, but there is plenty of funding available for well-structured deals. By building on the success of programmes such as OFTO (Offshore Transmission Owners), the Northern Line extension and the Thames Tideway Tunnel, the UK can be confident in developing a balanced approach to public and private finance to deliver desired outcomes at an affordable price.

06 / Case study: Thames Tideway Tunnel financing

This case study illustrates how an innovative approach to infrastructure funding has delivered an important asset to London with a reduced cost of finance. This outcome is a result of a carefully considered partnership between the public and private sectors to identify opportunities to minimise the risk premiums associated with private-sector project finance.

The Thames Tideway Tunnel (TTT) is a major project to construct a sewer tunnel running 25km from Acton in west London to Abbey Mills in east London, intercepting storm sewage overflows that would otherwise discharge into the Thames.

The project is currently estimated at 拢4.2bn, consisting of 拢3.2bn of works (including 拢500m contingency), and Thames Water鈥檚 preliminary enabling works estimated at 拢1.0bn. Work started in 2016, and TTT will be fully operational in 2024.

The project is to be delivered and financed privately. There are four key measures underpinning the success of the project structuring, which have reduced the cost of financing:

- transfer of some development risk to government

- creation of an early income stream through the application of user charges before completion

- staggering of financing requirements

- inclusion of contractual arrangements providing for assurance of performance.

The department in charge (Defra) took the view that that private delivery of the project would not be financially viable without some form of government support because of the scale of the project risks and the implications for financing costs that customers would ultimately fund.

Financing is structured around five building blocks:

Project finance

In terms of pre/post construction split, Thames Water was responsible for the preparatory works, which were funded on balance-sheet. For the remainder of the works, a special investment vehicle (SIV), Bazalgette (Tideway), was appointed as the infrastructure provider following a competitive tender process managed by Thames Water. The SIV is backed by six investors, including pension funds and other long-term investors. Shareholders committed 拢1.3bn in the form of equity (40%) and shareholder loans. The SIV is investing its capital to pay for construction works before bank debt funding is drawn down.

Good access to liquidity

On top of its initial capital, Tideway has raised substantial liquidity up front. On top of a 拢700m European Investment Bank loan, the SIV has been able early on to attract long-term, low-cost capital from banks and capital markets (US Private Placement and bond issue)

Government support package

Contingent financial support provided by the government aims to mitigate some of the risks, transferring liability to the taxpayer if those risks materialise. The arrangements aim at risk mitigation and early identification of potential calls on the support package.

User charges

Ultimately, the funding is recovered from the bills of Thames Water鈥檚 customer using a mechanism like the water utility investment model. Tunnel costs added 拢13 on average to customers鈥� annual bills in 2016-17 and are expected to add 拢20-拢25 in the early 2020s.

Contractual and regulatory arrangements

A strong, albeit somewhat untested, regulatory framework provides for regulated revenues during the construction period, with a forward-looking mechanism considering the planned investment profile. Bazalgette has been awarded a regulated utility licence and the project is subject to Ofwat鈥檚 five-year regulatory review process, based on its regulated asset value. The weighted average cost of capital is expected to be 2.497% until completion of construction and testing. Contractual arrangements for costs and payments (including 鈥減ain and gain sharing鈥�) provide Bazalgette and its contractors with financial incentives to deliver on time, or before, and manage the risks of cost overruns. Experience from costs on the tunnel鈥檚 sister project, the Lee Tunnel, has been used to improve estimates.

No comments yet